The New Word, by Allen Upward, [1910], at sacred-texts.com

Translation.—1. The Energy of Longing. 2. Diagram of Life.—3. The Art of Living.—4. Groundless Fear.—5. Ethical Sing-song.—6. The New Church.—7. The Unknown God.

BY this time the Testator's word has so far unfolded that we are able to see somewhat of his meaning.

The Swedish word for ideal seems to be höpp, the English hope, and a work of an idealist tendency to be neither more nor less than a hopeful work.

I

A hope differs from a thought, and an ideal from an idea, in that it has a tendency. It has going strength. It is not the builder's plan, but rather the householder's desire, of which the house is in some measure the fulfilment. It is indefinite because strength is indefinite, and if it were definite it would be dead.

Hope is a term of strength, like energy; it may be called the energy of longing. The children call it looking forward, which is the very etymology of idealist. It is by metaphor that we speak of a hope, or an ideal. That is an abstract word used as the name for an imaginary point towards which the

energy of longing works, and, as we have seen, it is an extreme point and an extravagant one. To fix the mind on this imaginary point instead of on the real strength is a cardinal error, and to refute it has been my first care in this interpretation. For the sound mind, the only real point is the Man Inside, whose circumference is the Man Outside; and the way of strength which is called Hope works between them.

All strength turns inside out, and we try to follow it with our names. The strength which leaves the sun as energy of light is called force of attraction whenas it leads the plant out of the soil, and the flower out of the plant; and again, within the flower, it is called energy of growth. Man is the flower and not the sun, and the attraction which leads the man out of the beast, and the angel out of the man, is known to himself as longing, or hope.

I have tried to show that this way of strength is as real as the force of gravitation. The swirl is the mathematical demonstration of hope, and the universe is the mathematical demonstration of the swirl. For there is an annex to the universe; but it is not built of words only, and it does not stand empty, but in it there abides an immortal Guest, whose name is Hope.

The Way of hope is marked off from the Way called heredity as the pull is marked off from the push. We are led as well as driven. Hope wrestles with heredity in the shaping of life, and

evolution is the triumph of hope over heredity. To say otherwise were to say that there is no growth, and no life.

Hope, therefore, must be half of the true story of creation. Beyond the struggle for existence is the struggle for a better existence. The survival of the fittest turns out to be the survival of the foremost, which is the creation of a higher type. The fittest for the past is not the fittest for the future, and it is the fittest for the future who is the elect of Hope. The Tree of Life grows upward, and it is the breath of life that has changed up into hope.

II

In its full meaning the word hope may be made to cover all man's work. It is hope that leads the veriest Materialist to learn from sense, and hope that turns the lesson to use for mankind's benefit. Nothing is so practical as hope. History itself is only busy idleness unless it can turn into prophecy.

But though hope spreads out fan-wise, instead of narrowing to a point, the Testator has clearly outlined the department of hope which he meant to endow. The Idealist is placed by him between the scientific discoverer on the one hand, and the practical pioneer of kindness on the other, both working for the benefit of mankind. Between these two the Idealist stands like an interpreter, whose business it should be to turn the lessons of science into rules of behaviour.

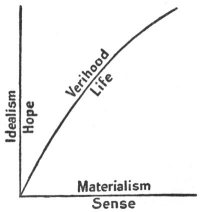

Idealism is first of all the science of hope, learning the will of Heaven from the voice within, as Materialism learns it from the voice without. So far as I can look into the mind of the Testator he sought in these two sciences, not a contradiction, but a collaboration, like that of the centripetal and centrifugal forces which are supposed to guide a planet in its course. This may be illustrated by a simple diagram:

The science of hope is languishing to-day, and I have thought it not the least part of this inquiry to investigate the causes of this aberration, and suggest

a remedy. Its chairs are filled, and its endowments are embezzled, by men who are still living in the Dark Age. They are good men, or so I like to think, but their work is not good, and they are blocking the way of better men. They seem to me like old women who should stand round a burning house with pails in their hands, faithfully throwing their paltry dribble on the flames, but keeping back the engine which alone can put out the fire. This legacy is certainly not meant for them. It is a summons to the firemen.

That seems to me the whole point. Here is not a prize for a new religion, for what is called science is the new religion. But here is a prize for a new hope, and it would not have been offered if the old hope were still strong and bright.

My chief end in this inquiry has been to show that this at bottom is a question of words, but to show at the same time that that does not lessen the importance of the question; because words are the signposts of hope. If the weathervane be stuck fast and useless, the wind will still blow, but that is no excuse for the weathervane. I have tried to show that the old words are outlandish words, as well as out-of-date words, and to point to where better words may be found. The folk-lore of the Black man has had a long innings in the North, and it is time to give the White man's folk-lore a turn. It is only my own judgment, but it is one not lightly nor hastily formed; and I think that the secret

lies here, and that this is the remedy for hope's disease.

It is a very gradual remedy, and that is why I hope so much from it. Before this Will can be fully carried out, before we can have truly hopeful works competing with one another for this Prize, we must have a generation, perhaps several generations, of writers who have been brought up on truth, and encouraged to write truthfully. For it is verihood that is difficult,—hope comes of its own accord wherever it has leave. But, to begin with, the mind must have light and air and freedom. The bandages must be taken off the brain. The laws against hope must be repealed.

The Idealist of our day works like the medieval alchemist by stealth and in dread of men, and his books are not sound and sensible. In the last generation an admired idealist wrote many books in praise of medieval churches and medieval manners and medieval hopes. Had this admired writer thoroughly asked himself the question,—To what end do we build to-day; what is our best hope; and in what building may we express it best?—had he gone to work in that spirit, then, although his search had ended in the bottom of a drain, he might have helped his fellows to build a better drain, and been not a preacher but a teacher.

On this head the Testator has left us in no doubt, that he did not want works of a useless tendency. He did not want beautiful words about hope, nor

words that would go round and round hope, but words that would help men to hope, and by helping them to hope, help them to live.

III

The Art of life is that high art which children name Behaviour, and as art is the end of science, so beautiful behaviour is the end of hope. If it were not so, Nobel would not have wasted his money on Idealism, nor I my labour. Here is the highest and most difficult art in the world, and yet the one in which each is called to be an artist; the art which any man, in any walk of life, may excel in, but in which no man may achieve perfection. Not even Kung the Master achieved perfection, if he is now worshipped alongside of Heaven. Not even the Buddha achieved perfection, if the Gods in Heaven now worship him.

When I look around me, and see so many men and women, of such differing creeds, of such varying degrees of knowledge, and under such manifold temptations, all trying to behave as well as their infirmities will let them, and behaving so much better than myself, I feel it is almost unkind to quarrel with them because their words are so much uglier than their deeds.

And yet nowhere, perhaps, are Andronican words much worse than in Talk about Behaviour, and nowhere are they more heedlessly flung out. The

word Love is the most dangerous in the dictionary. If we should ask any Christian to tell us the keyword of his religion, he would answer,—Love. And if we should ask any other man what religion had engendered the most hatred, he would answer,—Christianity. If those who use this word so recklessly would keep in mind that love and hate are in metastrophe; that the more they are loving in one direction, the more they are hating in another, and that it is hard for them to help one man without hurting another; if before they set out on those crusades of theirs, they would ask themselves, To whom am I going to be cruel?—how much more gentle their behaviour might become.

Again, as I walk through this world I hear going up from many earnest souls the cry,—Tell us how to behave! Teach us the Rule of Right! Make us a Moral Code!—And, unhappily as they think, happily as I think, no one knows quite how to behave; there is no Rule of Right; the Moral Code cannot be made. Not even the lawyers, with their magical sum of money, can make it; how much less then the mere moral philosophers and ethic-mongers, who have not even a Court.

The kindest saying I have found in all the words of men is this:—One man's meat is another man's poison. That is the idealist rule: not—Do unto others as you would that they should do unto you; but—Do unto others as they would have you do unto them.

Each of us has his own Moral Code, and makes it as he goes along, and changes it as his mind changes and grows. We know that the perfect Moneymaker will kill any one for a dollar, but that he makes an admirable Sunday-school teacher. We know that the perfect Idealist would make a poor policeman, but that if you were to set down a bag of gold on the desk in front of him, and afterwards take it away again, he would hardly notice what you were doing.

It is not well to be troubled over much even about behaviour. It is good for us sometimes to think that our behaviour does not matter very much to any one besides ourselves. The stars go on shining very steadily, summer and winter follow one another, the flowers spring up in their season, and the songbirds carol in the sky.

TV

Why is it that, while I see everywhere around me men whose manners are better than their words, yet they are all anxious to persuade me that it is the words that bring about the good manners? The astrologers seem to have persuaded them that a reform of the kalendar will be followed by bloodshed in the streets.

Much of this seems to be the backwash of the great French Revolution. The educated European mind has been marking time for a hundred years,

out of fear of the mob. Frederick of Prussia, Catherine of Russia, that strange, ill-starred Idealist on a throne who founded the Swedish Academy, were all more enlightened than kings have ventured to be since. The Revolution frightened the rich. And the astrologers have seen their opportunity. They have persuaded the poor rich men that that great jacquerie was a scientific orgy. There were no starving serfs up and down France. There were no heartless, worthless lords. There was no bankrupt, foolish king. There was no Bastille for idealists; and no Idealist named Rousseau. The kingship did not bring the kingdom to utter wreck, and then call in a desperate mob to put things straight for it. The old régime did not commit suicide. No; all that is a mistake. There was a wit named Voltaire, and he was allowed to say witty things about the astrologers, and because of that the mob rose and cut the rich men's throats.—And because of that Mammon to-day sits on guard, with his Mass-book in one hand, and his Maxim in the other, watching for Truth as a terrier watches for a rat.

The policy of the poor, frightened rich men is the policy of the ostrich. They build their churches, and patch up their cathedrals, and hire respectable clergymen at enormous salaries to make-believe that the earth is flat,—and meanwhile Columbus has discovered the new world, and Copernicus has discovered the sun, and Darwin has discovered life. And not one of the poor rich men is a penny the worse.

Their fear is groundless. No one wants to cut their throats. No one wants to rob them. The Socialist wants them to pay their poor-rate, and by withholding it they create Socialism. The poor man asked them for bread, and they have given him a vote; and now they must pay in taxes more than they refused as alms. The Idealist is not thinking of their gold at all. He is not asking bread but freedom. And Hope is a dangerous prisoner.

On the whole there never has been a time during the last two thousand years when the astrology had so little real hold on men's minds as it has to-day, and there never has been a time when the behaviour of men towards one another was on the whole so good. The untightening of dogma and the bettering of behaviour have pretty nearly kept pace together. And a hundred years after the French Revolution a White folk, called on to choose between kingship and commonwealth, have chosen kingship.

Who was the first to write under words like—"The kingdom of heaven is within your own hearts"—the label "Poetry"; and under words like—"Where the worm dieth not, and the fire is not quenched"—the label "Exact Geography"? The story of the Good Samaritan is not an astrological myth. The good seed of the Idealist has been choked by the astrologer's tares.

V

There is a slang word in use among us, cant, which seems to be in English sing-song. It is our old enemy the magic spell, but in its dotage, and grown too feeble to withstand any searching test. It is more beloved in England than in any other country in the world, and for that very reason. The English are a practical people, and the spell that gives way most readily before a sum of money is the one that suits them best. It is not easy for foreigners to understand the English character. You think that they are fighting to the death over whether their children shall be taught the gospel according to Queen Elizabeth, or the gospel according to the London County Council; but when you go among them, you find that they do not mind what their children are taught, so long as they do not have to pay for it; that the whole quarrel is over that; and that quite a number of them are cheerfully sending their children to schools opened by the cast-out monks and nuns of other countries, to be taught the gospel according to Ignatius Loyola.

Let us see if we can talk about behaviour without dropping into sing-song.

It seems to be true that there is hardly anything, from mother-slaying down to Sabbath-breaking, which one man at one time thinks to be right, which

another man at another time, or even at the same time, does not think to be wrong. I cannot think of anything which is to-day in one country punished as a crime which has not been yesterday, or in another country, practised as a virtue and preached as a religion. In our own time and country, while every one repeats the same moral Hic haec hoc, each one interprets it to please himself, and keeps it or breaks it as his wishes prevail over his fears.

In order to learn how men really feel about behaviour there seems to be no way open but to look past what they are saying to what they are doing. And accordingly, when I wish to find a moral code that really is believed in and obeyed, when I want to find the true Levitical law of the age, I have to put on one side all the Ethical masterpieces, all the tomes of Moral Philosophy, all the sermons and the tracts, and to begin with a very humble, and not at all distinguished, treatise calling itself the Book of Etiquette.

The Book of Etiquette is, according to its lights, the book of the knowledge of good and evil behaviour. It is wonderfully free from sing-song. It does not use many Andronican words. It does not take high ground with its readers; it only tells them how they must behave if they wish to be thought ladies and gentlemen. It utters no threats; it holds up no punishments. And yet I find there is no lawgiver so willingly obeyed as the lawgiver who writes this little book. When must I call on my friends;

how many cards must I leave; how many minutes must I stay?—such are the things I may learn, if I will, from this remarkable book.

The Book of Etiquette is sometimes sneered at for teaching its readers to ape their betters. But I see nothing to sneer at; and to ape our betters seems to me a very beautiful thing to do, and a very touching thing; and I would far rather see my fellows anxious to be thought ladies and gentlemen, than hear them using words like Humanity and Brotherhood. I find nothing about bombs in the Book of Etiquette. And if the people of England should ever look at it from my point of view, they will sink their differences about Queen Elizabeth, and begin from the beginning with the Book of Beautiful Behaviour.

For it is a work of a hopeful tendency.

VI

There have been times when I have been tempted to join those good men who are trying to reform the Church. And then again I have looked at that lightning conductor, and seen that it was reforming the church faster than any words of theirs or mine could do. In the end I have looked round me and found growing up unawares the New Church.

The Club is to the Book of Etiquette what the Church was to theology. It is the real thing instead

of the explanation, the house and not the plan. If we wish to learn how men feel about behaviour today, we must go to the clubs. They are the Œcumenical Council of our time, with power to bless and to curse. No one any longer minds being excommunicated by this or that clerical authority, but everybody minds being expelled by his club. The old priesthood no longer dares to beard the sinner by name, if he live any nearer than Constantinople. The new priesthood takes the sinner by the scruff of his neck, and thrusts him out.

The new Church does not deal in Andronican language. All its theology and ethics are summed up in the two short words—Good Form. And perhaps those are the only ethical words in use among us which are never sing-song. So, while the moral philosophers are writing their moral codes, and the teachers of ethics are piling up their Mediterranean words, the clubs have quietly got hold of their own unwritten code, and are shaping mankind by it.

Now the grand merit which I find in this new church is that it is not a catholic church. It is the other way about. It is the Exclusive Church. It does not force the sinner and the dissenter to come in, but tries its very hardest to keep them outside. And in that I find more hope for mankind than in any other observation I have made since I came to live among them.

When we have laid the lesson of the Club to heart, the world will be changed. We shall no

longer try to take the Black Man into the White Man's Club against our will, nor the Yellow Man against his will. There will be no more great empires, and no more oppressed nationalities; no more crusades, and therefore no more pilgrimages of peace. There will be no more laws, and no more prisons. There will be no more creeds, and no more catechisms,—and the catechisms are a thousandfold more wicked than the creeds.

For the Clubs are not all alike, neither are they meant to be all alike. They are meant to sort out men and women, each into his own Club, to the end that they may enjoy themselves, without marring the enjoyment of others. In the long-run they tend to mount in an upward spiral, and to draw the Rules of Good Manners from the highest Club. And that is how Hope works in the evolution of behaviour.

The Coming Man is there. He is the member of the highest Club. And, as I hope, he will be neither the furious enslaver of millionairism, nor the ticketed and machine-made doll of socialism, neither will he be like the mad saint of the Dark Age. He will be first and foremost a good-tempered Man, trying to play the Game according to the Rules, and ever ready to learn, and to change the Rules of the Club when the Rules of the Game are being changed by the Man Outside. I foresee that he will not all at once beat his sword into a ploughshare, but that he will in time put a button on his foil, and that when he finds he must fight, he will

fall on, not spitting and snarling like a beast, but like a gentleman, raising his sword to the salute, and keeping loyally the Rules of the Fencing School.

VII

Now I have done putting together these sticks and straws of verihood and falsehood; and I have woven a nest, but how unlike that dome which only hope can build! I have woven it, as though round my own mind, and yet it does not altogether follow the shape of my own mind. So does the bee, working in the midst of other bees, to fashion its round cell, find at the last that it has wrought a hexagon, for so has overwrought the bee outside.

The man outside me all this time has been my Testator, with whom I have wrought as a faithful. wordsmith, striking blow for blow, to forge upon the anvil of sense a definition of hope that should ring true in the ear of the Materialist as well as of the Idealist.

I read this great Bequest as a bequest to Hope, but not to every hope. I read it as a bequest to the highest hope, and to the Interpretation of that Hope. I read it as a prayer for Light. I read it as the prayer of one who walked in darkness, but hoped for light; and as an appeal from the darkness to the Light.

I have seen an altar to the Unknown God.