) in Haṭha Yoga are compulsory on the student and that besides being dirty, they are fraught with danger to the practiser. This is not true, for these practices are necessary only in the existence of impurities in the Nâdis, and not otherwise.

) in Haṭha Yoga are compulsory on the student and that besides being dirty, they are fraught with danger to the practiser. This is not true, for these practices are necessary only in the existence of impurities in the Nâdis, and not otherwise.Hatha Yoga Pradipika, tr. by Pancham Sinh, [1914], at sacred-texts.com

There exists at present a good deal of misconception with regard to the practices of the Haṭha Yoga. People easily believe in the stories told by those who themselves heard them second hand, and no attempt is made to find out the truth by a direct reference to any good treatise. It is generally believed that the six practices, (

) in Haṭha Yoga are compulsory on the student and that besides being dirty, they are fraught with danger to the practiser. This is not true, for these practices are necessary only in the existence of impurities in the Nâdis, and not otherwise.

) in Haṭha Yoga are compulsory on the student and that besides being dirty, they are fraught with danger to the practiser. This is not true, for these practices are necessary only in the existence of impurities in the Nâdis, and not otherwise.

There is the same amount of misunderstanding with regard to the Prâṇâyâma. People put their faith implicitly in the stories told them about the dangers attending the practice, without ever taking the trouble of ascertaining the fact themselves. We have been inspiring and expiring air from our birth, and will continue to do so till death; and this is done without the help of any teacher. Prâṇâyâma is nothing but a properly regulated form of the otherwise irregular and hurried flow of air, without using much force or undue restraint; and if this is accomplished by patiently keeping the flow slow and steady, there can be no danger. It is the impatience for the Siddhis which cause undue pressure on the organs and thereby causes pains in the ears, the eyes, the chest, etc. If the three bandhas (

) be carefully performed while practising the Prâṇâyâma, there is no possibility of any danger.

) be carefully performed while practising the Prâṇâyâma, there is no possibility of any danger.

There are two classes of students of Yoga: (1) those who study it theoretically; (2) those who combine the theory with practice.

Yoga is of very little use, if studied theoretically. It was never meant for such a study. In its practical form, however, the path of the student is beset with difficulties. The books on Yoga give instructions so far as it is possible to express the methods in words, but all persons, not being careful enough to follow these instructions to the very letter, fail in their object. Such persons require a teacher versed in the practice of Yoga. It is easy to find a teacher who will explain the language of the books, but this is far from being satisfactory. For instance, a Pandit without any knowledge of the science of Materia Medica will explain

as

as

or an enemy of thorns, i.e., shoes, while it is in reality the name of a medicinal plant,

or an enemy of thorns, i.e., shoes, while it is in reality the name of a medicinal plant,

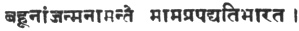

The importance of a practical Yogî as a guide to a student of Yoga cannot be overestimated; and without such a teacher it is next to impossible for him to achieve anything. The methods followed by the founders of the system and followed ever afterwards by their followers, have been wisely and advisedly kept secret; and this is not without a deep meaning. Looking to the gravity of the subject and the practices which have a very close relation with the vital organs of the human body, it is of paramount importance that the instructions should be received by students of ordinary capacity, through a practical teacher only, in order to avoid any possibility of mistake in practice. Speaking broadly, all men are not equally fitted to receive the instructions on equal terms. Man inherits on birth his mental and physical capitals, according to his actions in past births, and has to increase them by manipulation, but there are, even among such, different grades. Hence, one cannot become a Yogî in one incarnation, as says Śri Kṛiṣṇa

and again

and again

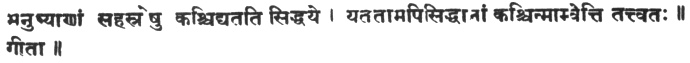

There are men who, impelled by the force of their actions of previous births, go headlong and accomplish their liberation in a single attempt; but others have to earn it in their successive births. If the student belongs to one of such souls and being earnest, desires from his heart to get rid of the pains of birth and death, he will find the means too. It is well-known that a true Yogî is above temptations and so to think that he keeps his knowledge secret for selling it to the highest bidder is simply absurd. Yoga is meant for the good of all creatures, and a true Yogî is always desirous of benefitting as many men as possible. But he is not to throw away this precious treasure indiscriminately. He carefully chooses its recipients, and when he finds a true and earnest student, who will not trifle with this knowledge, he never hesitates in placing his valuable treasure at the disposal of the man. What is essential in him is that he should have a real thirst for such knowledge—a thirst which will make him restless till satisfied; the thirst that will make him blind to the world and its enjoyments. He should be, in short, fired with

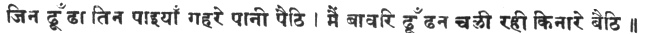

or desire for emancipation. To such a one, there is nothing dearer than the accomplishment of this object. A true lover will risk his very life to gain union with his beloved like Tulasîdâs. A true lover will see everywhere, in every direction, in every tree and leaf, in every blade of grass his own beloved. The whole of the world, with all its beauties, is a dreary waste in his eyes, without his beloved. And he will court death, fall into

or desire for emancipation. To such a one, there is nothing dearer than the accomplishment of this object. A true lover will risk his very life to gain union with his beloved like Tulasîdâs. A true lover will see everywhere, in every direction, in every tree and leaf, in every blade of grass his own beloved. The whole of the world, with all its beauties, is a dreary waste in his eyes, without his beloved. And he will court death, fall into

the mouth of a gaping grave, for the sake of his beloved. The student whose heart burns with such intense desire for union with Paraṃâtmâ, is sure to find a teacher, and through him he will surely find Him It is a tried experience that Paraṃâtmâ will try to meet you half way, with the degree of intensity with which you will go to meet Him. Even He Himself will become your guide, direct you on to the road to success, or put you on the track to find a teacher, or lead him to you.

Well has it been said

It is the half-hearted who fail. They hold their worldly pleasures dearer to their hearts than their God, and therefore He in His turn does not consider them worthy of His favours. Says the Upaniṣad:—

It is the half-hearted who fail. They hold their worldly pleasures dearer to their hearts than their God, and therefore He in His turn does not consider them worthy of His favours. Says the Upaniṣad:—

The âtmâ will choose you its abode only if it considers you worthy of such a favour, and not otherwise. It is therefore necessary that one should first make oneself worthy of His acceptance. Having prepared the temple (your heart) well fitted for His installation there, having cleared it of all the impurities which stink and make the place unsuitable for the highest personage to live in, and having decorated it beautifully with objects as befit that Lord of the creation, you need not wait long for Him to adorn this temple of yours which you have taken pains to make it worthy of Him. If you have done all this, He will shine in you in all His glory. In your difficult moments, when you are embarrassed, sit in a contemplative mood, and approach your Parama Guru submissively and refer your difficulties to Him, you are sure to get the proper advice from Him. He is the Guru of the ancients, for He is not limited by Time. He instructed the ancients in bygone times, like a Guru, and if you have been unable to find a teacher in the human form, enter your inner temple and consult this Great Guru who accompanies you everywhere, and ask Him to show you the way. He knows best what is best, for you. Unlike mortal beings, He is beyond the past and the future, will either send one of His agents to guide you or lead you to one and put you on the right track. He is always anxious to teach the earnest seekers, and waits for you to offer Him an opportunity to do so. But if you have not done your duty and prepared yourself worthy of entering His door, and try to gain access to His presence, laden with your unclean burden, stinking with Kama, Krodha, Lobha, and Moha, be sure He will keep you off from Him.

The Âsanas are a means of gaining steadiness of position and help to gain success in contemplation, without any distraction of the mind. If the position be not comfortable, the slightest inconvenience will draw the mind away from the lakśya (aim), and so no peace of mind will be possible till the posture has ceased to cause pain by regular exercise.

Of all the various methods for concentrating the mind, repetition of Praṇava or Ajapâ Jâpa and contemplation on its meaning is the best. It is impossible for the mind to sit idle even for a single moment, and, therefore, in order to keep it well occupied and to keep other antagonistic thoughts from entering it, repetition of Praṇava should be practised. It should be repeated till Yoga Nidrâ is induced which, when experienced, should be encouraged by slackening all the muscles of the body. This will fill the mind with sacred and divine thoughts and will bring about its one-pointedness, without much effort.

Anâhata Nâda is awakened by the exercise of Prâṇâyâma. A couple of weeks’ practice with 80 prâṇâyâmas in the morning and the same number in the evening will cause distinct sounds to be heard; and, as the practice will go on increasing, varied sounds become audible to the practiser. By hearing these sounds attentively one gets concentration of the mind, and thence Sahaja Samâdhi. When Yoga sleep is experienced, the student should give himself up to it and make no efforts to check it. By and by, these sounds become subtle and they become less and less intense, so the mind loses its waywardness and becomes calm and docile; and, on this practice becoming well-established, Samâdhi becomes a voluntary act. This is, however, the highest stage and is the lot of the favoured and fortunate few only.

During contemplation one sees, not with his eyes, as he does the objects of the world, various colours, which the writers on Yoga call the colours of the five elements. Sometimes, stars are seen glittering, and lightning flashes in the sky. But these are all fleeting in their nature.

At first these colours are seen in greatly agitated waves which show the unsteady condition of the mind; and as the practice increases and the mind becomes calm, these colour-waves become steady and motionless and appear as one deep ocean of light. This is the ocean in which One should dive and forget the world and become one with his Lord—which is the condition of highest bliss.

Faith in the practices of Yoga, and in one's own powers to accomplish what others have done before, is of great importance to insure speedy success. I mean "faith that will move mountains," will accomplish

anything, be it howsoever difficult. There is nothing which cannot be accomplished by practice. Says Śiva in Śiva Saṃhitâ.

Through practice success is obtained; through practice one gains liberation.

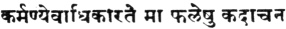

Perfect consciousness is gained through practice; Yoga is attained through practice; success in mudrâs comes by practice. Through practice is gained success in Prâṇâyâma. Death can be evaded of its prey through practice, and man becomes the conqueror of death by practice. And then let us gird up our loins, and with a firm resolution engage in the practice, having faith in

, and the success must be ours. May the Almighty Father, be pleased to shower His blessings on those who thus engage in the performance of their duties. Om Siam.

, and the success must be ours. May the Almighty Father, be pleased to shower His blessings on those who thus engage in the performance of their duties. Om Siam.

PANCHAM SINH.

AJMER:

31st January, 1915.