Fictitious and Symbolic Creatures in Art, by John Vinycomb, [1909], at sacred-texts.com

Fictitious and Symbolic Creatures in Art, by John Vinycomb, [1909], at sacred-texts.com

"What, always dreaming over heavenly things,

Like angel heads in stone with pigeon wings."

Cowper, "Conversation."

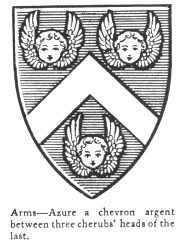

In heraldry A Cherub (plural Cherubim) is always represented as the head of an infant between a pair

|

A Seraph (plural Seraphim), in like manner, is always depicted as the head of a child, but with three pairs of wings;

|

Clavering, of Callaby Castle, Northumberland, bears for crest a cherub's head with wings erect. Motto: cœlos volens.

On funereal achievements, setting forth the rank

and circumstance of the deceased, it is usual to place over the lozenge-shaped shield containing arms of a woman, whether spinster, wife, or widow, a cherub's head, and knots or bows of ribbon in place of crests, helmets, or its mantlings, which, according to heraldic law, cannot be borne by any

|

In representing the cherubim by infants’ winged heads, the early painters meant them to be emblematic of a pure spirit glowing with love and intelligence, the head the seat of the soul, and the wings attribute of swiftness and spirit alone retained.

The body or limbs of the cherub and seraph are never shown in heraldry, for what reason it is difficult to say, unless it be from the ambiguity of the descriptions in the sacred writings and consequent difficulty of representing them. The heralds adopted the figure of speech termed synecdoche, which adopts a part to represent the whole.

Sir Joshua Reynolds has embodied the modern conception in his exquisite painting of cherubs’ heads, Portrait Studies of Frances Isabella Ker, daughter of Lord William Gordon, now in the National Collection. It represents five infants’ heads with wings, in

different positions, floating among clouds. This idea of the cherub seems to have found ready acceptance with poets and painters. Shakespeare sings:

Many of the painters of the period of the Renaissance represented the cherub similarly to those in Reynolds’ picture. They were also in the habit of introducing into their pictures of sacred subjects nude youthful winged figures, "celestial loves," sporting in clouds around the principal figure or figures, or assisting in some act that is being done. Thus Spenser invests "The Queen of Beauty and of Love the Mother" with a troop of these little loves, "Cupid, their elder brother."

[paragraph continues] These must not, however, be confounded with the cherub and seraph of Scripture. It was a thoroughly

pagan idea, borrowed from classic mythology, and unworthy of Christian Art. It soon degenerated into "earthly loves" and "cupids," or amorini as they were termed and as we now understand them.