Fictitious and Symbolic Creatures in Art, by John Vinycomb, [1909], at sacred-texts.com

Fictitious and Symbolic Creatures in Art, by John Vinycomb, [1909], at sacred-texts.com

As the Lion is the king of beasts, the Eagle the king of birds, so in similar heraldic sense the Dolphin is king of fishes. His position in legend is probably due to his being one of the biggest and boldest creatures of the sea that passed the Pillars of Hercules into the Mediterranean Sea. Pliny (Book ix. ch. 8) calls it "The swiftest of all other living creatures whatsoever, and not of sea fish only, is the dolphin; quicker than any fowle, swifter than the arrow shot from a how."

The dolphin, of which there are several varieties,

enjoys a pretty wide geographical distribution, being found in the Arctic seas, the Atlantic Ocean, and indeed of all seas. It was well known to the ancients and furnished the theme of many a fabulous story.

The common dolphin (Delphinus Delphis) the true hieros ichthus, is only rarely met with on the British coast. Its

|

Unlike its near relatives the porpoises, who haunt the coast, dolphins live far out at sea, and are gene-. rally mistaken for porpoises. The long-snouted dolphin feeds on pelagic fishes. The short-nosed porpoise likes salmon and mackerel, robs the fishermen's nets, and even burrows in the sand in search of odds and ends. The dolphin is the sea-goose.

[paragraph continues] The porpoise is the sea-pig; he is the porc-poisson, the porc-pois, or sea-hog.

The convex snout of the dolphin is separated from the forehead by a deep furrow; the muzzle is greatly extended, compressed, and much attenuated especially towards the apex, where it terminates in a rather sharp-pointed beak. The French name bec d’oie, from the great projection of its nose or beak, has led to its adoption in the arms of English families of the name of Beck. The dolphin is an elegant and swift swimmer, and capable of overtaking the swiftest of the finny tribe. Because the creature is noted for its swiftness it has been adopted in the arms of Fleet.

The dolphin is able to hold his own against nearly all others of his size and weight, and even some of the larger cetaceans only come off second best in an encounter with the dolphin. He is voracious, gluttonous, and ever on the look out for something to turn up, hunting his prey with great persistency and devouring it with avidity. He has been not inaptly styled "the plunderer of the deep."

The destructive character of the dolphin amongst the various tribes of fish is not lessened when we examine its formidable jaws studded with an immense number of interlocking teeth. Notwithstanding its rapacious habits and the variety of its diet it was in England formerly regarded as a royal fish, and its flesh held in high estimation. Old chroniclers have frequent entries of dolphins being caught in the Thames, thus: "3 Henry V.—Seven dolphins came

up the Thames, whereof four were taken." "14th Richard II.—On Christmas Day one was taken at London Bridge, being ten feet long, and a monstrous grown fish." (Delalune's "Present State of London," 1681.) The early fathers of the Church deemed "all fish that swam in the sea"; the dolphin was therefore eaten in Lent. He is, however, a mammal, not a fish, and though an air-breathing creature he lives and dies in the ocean. But one is brought forth at a birth, and between the old and young of their kind, as in the case of all marine animals, a strong affection exists.

Travellers’ tales are notoriously hard of belief, and must be taken cum grano salis. We learn from Sir Thomas Herbert, an early voyager, that when he was on the coast of Sanquehar, a large kingdom on the east side of the Cape of Good Hope, he "saw there great numbers of dolphins," of which he says: "They much affect the company of men, and are nourished like men; they are always constant to their mates, tenderly affected to their parents, feeding and defending them against hungry fishes when they are old," and much more information equally astonishing.

A story is related of a man who once went to a mufti and asked him whether the flesh of the sea-pig (the dolphin) was lawful food. Without any hesitation the mufti declared that pig's flesh was unlawful at all times and under all circumstances. Some time after another person submitted the question to the same authority, whether the fish of the sea, called the sea-pig,

was lawful food. The mufti replied: "Fish is lawful food by whatever name it may be called."

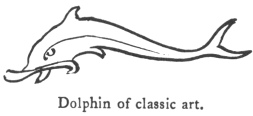

Classic Fable and Mediæval Legend have shed a halo of romantic interest around the dolphin which cleaves to it even to the present hour; the rare event of a dolphin being caught in British waters revives with a thrill all the old-world stories and historic associations of this famous fish as if it were a veritable relic of the golden age. The dolphin of fact we have found to be quite a different creature from what he is pictured by the ancients. The mariner may be engulfed by "the yawning, dashing, furious sea," but no generous dolphin now watches with tender eye, solicitous for his safety, nor offers his ready back to speed him to the shore.

The dolphin of our modern poets and sailors—the swift swimmer that leaps after the flying-fish and frolics in front of the vessel's prow until he is caught by the glittering tin—is the Coryphæna hippurus, the species famed for its changing tints when taken from the water. During a calm, these fishes, when swimming about a ship, appear of a brilliant blue or purple, shining with a metallic lustre in every change of reflected light. On being captured and brought on deck, the variety of these tints is very beautiful. The bright purple and golden yellow hues change to brilliant silver, varying back again into the original colours, purple and gold. This alteration of tints continues for some time, diminishing in intensity, and at last settles down into a dull leaden hue. The iridescent

lines which play along its elegant curves as he lies on deck has awakened the enthusiasm of many a writer. Byron tells us in a beautiful simile:

It is needless to say that the legendary dolphin is not to be confounded with the gay and graceful coryphæna to whom alone

|

The dolphin (δελφίν) may be considered an accessory symbol of Apollo, who, as we read in the Homeric hymns, once took the form of a dolphin when he guided the Cretan ship to Crissa, whence, after commanding the crew to burn the ship and erect an altar to him as Apollo Delphinios, he led them to

[paragraph continues] Delphi, and appointed them to be the first priests of his temple.

The dolphin is the most classic of fishes, the favourite of Apollo, and sacred to that bright divinity, deriving his name from the oracular Delphi, that mysterious spot, "the earth's umbilicus," the very centre of the world, Delphi or Delphos, a town in Phocis, famous for its oracle in the Temple of Apollo, upon the walls of which were sculptured the Helios ichthus, Apollo's fish.

In the legend of Tarento, Phalantus, heading the Patheniæ, was driven from Sparta and shipwrecked off the coast of Italy, and escaped on a friendly dolphin's back to Tarentum. We learn from Aristotle that the youthful figure seated on the dolphin, which is the most common type on the coins of this city, was intended for Taras, a son of Poseidon, from whom the city is said to have derived its name.

The dolphins, "the arrows of the sea," were the great carriers of ancient times. Not only did they bear the Nereides safely on their backs, but Arion, the sweet singer, when forced to leap into the sea to escape the mariners who would have murdered him, had previously so charmed the dolphins by his playing that they gathered round the ship and one of them bore Arion safely to Tænarus, whilst the musician

[paragraph continues] The classic myth of Arion and the dolphin, like

many other pagan fictions, was invested by the early Christians with an entirely different signification, and in the sculptures and frescoes of the catacombs and other symbolic representations of the Christian converts, the frequent introduction of the dolphin "points not to the deliverer of Arion, but to Him who through the waters of baptism opens to mankind the paths of deliverance, causing them to so pass the waves of this troublesome world that finally they may come to the land of everlasting life."

The poet Licophron says Ulysses bore a dolphin on his shield, on the pommel of his sword, as well as on his ring, in commemoration of the extraordinary escape of his son Telemachus, who when young fell into the sea and was taken up by a dolphin and safely brought on shore. Pliny and others relate a story of one of these fishes which frequented the Lake Lucrin: "A boy who went every day to school from Baia to Puzzoli used to feed this dolphin with bread, and it became at last so familiar with the boy that it carried him often on its back over the bay."

The dolphins were early symbols on the coins of Ægina, and though abandoned for a time were afterwards resumed; and they appear upon later and well-known coins of that State accompanied by the wolf and other national devices. Argos had anciently two dolphins; Syracuse, a winged sea-dog, a dolphin, &c.; Teneos (Cyclades) two dolphins and a trident. The dolphin and trident figures also upon coins of

the ancient city of Byzantium, signifying probably the sovereignty of the seas. It is even figured by the ancients as a constellation in the heraldry of the

|

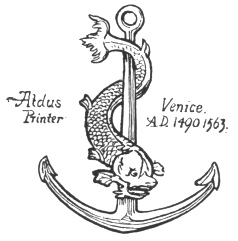

The dolphin and anchor is a famous historic symbol. Titus, Emperor of Rome, took the device of a dolphin twisted round an anchor, to imply, like the emblem of Augustus, the medium between haste and slowness, the anchor being the symbol of delay, as it is also of firmness and security, while the dolphin is the swiftest of fish. This device appears also upon the coins of Vespasian, the father of Titus. The anchor was also used as a signet ring by Seleneus, King of Syria. The dolphin and anchor was also used, with the motto "Festina lente" ("Hasten slowly"), by the Emperor Adolphus of Nassau, and by Admiral Chabot. The family of Onslow bear the same for crest and motto.

Aldus Manutius, the celebrated Venetian printer, adopted this well-known device from a silver medal presented to him by Cardinal Bembo, with the motto in Greek "hasten slowly." Camerarius describes this sign in his book of symbols "to represent that maturity in business which is the medium between too great haste and slowness." "When violent winds disturb the sea the anchor is cast by seamen, the dolphin

winds herself round it out of a particular love for mankind, and directs it as with a human intellect so that it may more

|

This sign was afterwards adopted by William Pickering, a worthy "Discipulus Aldi" as he styles himself. Sir Egerton Bridges has some verses upon it, amongst which occur the following:

. . . . .

"Nor time nor envy shall ever canker,

The sign which is my lasting pride;

Joy then to the Aldus anchor

And the dolphin at its side.

The dolphin was the insignia of the Eastern Empire—the Empire of Constantinople. The Courteneys, a noble Devonshire family, still bear the dolphin as crest and badge, and the melancholy motto, "Ubi lapsus? Quid feci?" ("Whither have I fallen? What have I done?"), a touching allusion," says Miss Millington ("Heraldry in History and Romance"), "to the misfortunes of their race, three of whom filled the imperial throne of Constantinople during the time that city was in possession of the Latins after the siege of 1204. Expelled at length by the Greeks, Baldwin, the last of the three, wandered from Court to Court throughout Europe vainly seeking aid to replace him upon the throne."

A branch of the imperial Courteneys settled in England during the reign of Henry II., and their descendants were among the principal Barons of the realm. Three Earls of Courteney perished on the scaffold during the Wars of the Roses; the family was restored to favour by Henry VII. Another Courteney, the Marquis of Exeter, became first the favourite, and subsequently the victim of the brutal tyrant Henry VIII. His son Edward, after being long a prisoner in the tower, ended his days in exile, and the family estates passed into other hands.

Sir William Courteney, of Powderham Castle,

[paragraph continues] Devon (temp. Edw. IV.), bore emblazoned on his standard three dolphins in reference to the purple of three Emperors.

The Arms of Peter Courteney, Bishop of Exeter, 1478, is still to be seen in the episcopal palace environed with the dolphins of Constantinople.