Click to enlarge

THE MOUSE TOWER, NEAR BINGEN

LOUIS WEIRTER, R.B.A.

Facing page 206.

In the imperial fortress of Falkenburg dwelt the beautiful Liba, the most charming and accomplished of maidens, with her widowed mother. Many were the suitors who climbed the hill to Falkenburg to seek the hand of Liba, for besides being beautiful she was gentle and virtuous, and withal possessed of a modest fortune left her by her father. But to all their pleadings she turned a deaf ear, for she was already betrothed to a young knight named Guntram whom she had known since childhood, and they only waited until Guntram should have received his fief from the Palsgrave to marry and settle down.

One May morning, while Liba was seated at a window of the castle watching the ships pass to and fro on the glassy bosom of the Rhine, she beheld Guntram riding up the approach to Falkenburg, and hastened to meet him. The gallant knight informed his betrothed that he was on his way to the Palsgrave to receive his fief, and had but turned aside in his journey in order to greet his beloved. She led him into the castle, where her mother received him graciously enough, well pleased at her daughter's choice.

"And now, farewell," said Guntram. "I must hasten. When I return we two shall wed; see to it that all is in readiness."

With that he mounted his horse and rode out of the courtyard, turning to wave a gay farewell to Liba. The maiden watched him disappear round a turn in the winding path, then slowly re-entered the castle.

Meanwhile Guntram went on his way, and was at length invested with his fief. The Palsgrave, pleased with the manners and appearance of the young knight, appointed him to be his ambassador in Burgundy, which honour Guntram, though with much reluctance, felt it necessary to accept. He dispatched a messenger to his faithful Liba, informing her of his appointment, which admitted of no delay, and regretting the consequent postponement of their marriage. She, indeed, was ill-pleased with the tidings and felt instinctively that some calamity was about to befall. After a time her foreboding affected her health and spirits, her former pursuits and pleasures were neglected, and day after day she sat listlessly at her casement, awaiting the return of her lover.

Guntram, having successfully achieved his mission, set out on the homeward journey. On the way he had to pass through a forest, and, having taken a wrong path, lost his way. He wandered on without meeting a living creature, and came at last to an old dilapidated castle, into the courtyard of which he entered, thankful to have reached a human habitation. He gave his horse to a staring boy, who looked at him as though he were a ghost.

"Where is your master?" queried Guntram.

The boy indicated an ivy-grown tower, to which the knight made his way. The whole place struck him as strangely sombre and weird, a castle of shadows and vague horror. He was shown into a gloomy chamber by an aged attendant, and there awaited the coming of the lord. Opposite him was hung a veiled picture, and half hoping that he might solve the mystery which pervaded the place, he drew aside the curtain. From the canvas there looked out at him a lady of surpassing beauty, and the young knight started back in awe and admiration.

In a short time the attendant returned with a thin, tall old man, the lord of the castle, who welcomed the guest with grave courtesy, and offered the hospitality of his castle. Guntram gratefully accepted his host's invitation, and when he had supped he conversed with the old man, whom he found well-informed and cultured.

"You appear to be fond of music," said the knight, indicating a harp which lay in a corner of the room.

He had observed, however, that the strings of the harp were broken, and that the instrument seemed to have been long out of use, and thought that it possibly had some connexion with the original of the veiled portrait. Whatever recollections his remark aroused must have been painful indeed, for the host sighed heavily.

"It has long been silent," he said. "My happiness has fled with its music. Good night, and sleep well." And ere the astonished guest could utter a word the old man abruptly withdrew from the room.

Shortly afterward the old attendant entered, bearing profuse apologies from his master, and begging that the knight would continue to accept his hospitality. Guntram followed the old man to his chamber. As they passed through the adjoining apartment he stopped before the veiled portrait.

"Tell me," he said, "why is so lovely a picture hidden?"

"Then you have seen it?" asked the old keeper. "That is my master's daughter. When she was alive she was even more beautiful than her portrait, but she was a very capricious maid, and demanded that her lovers should perform well-nigh impossible feats. At last only one of these lovers remained, and of him she asked that he should descend into the family vault and bring her a golden

crown from the head of one of her ancestors. He did as he was bidden, but his profanation was punished with death. A stone fell from the roof and killed him. The young man's mother died soon after, cursing the foolish maid, who herself died in the following year. But ere she was buried she disappeared from her coffin and was seen no more."

When the story was ended they had arrived at the door of the knight's chamber, and in bidding him good night the attendant counselled him to say his paternoster should anything untoward happen.

Guntram wondered at his words, but at length fell asleep. Some hours later he was awakened suddenly by the rustling of a woman's gown and the soft strains of a harp, which seemed to come from the adjoining room. The knight rose quietly and looked through a chink in the door, when he beheld a lady dressed in white and bending over a harp of gold. He recognized in her the original of the veiled portrait, and saw that even the lovely picture had done her less than justice. For a moment he stood with hands clasped in silent admiration. Then with a low sound, half cry, half sob, she cast the harp from her and sank down in an attitude of utter despondency. The knight could bear it no longer and (quite forgetting his paternoster) he flung open the door and knelt at her feet, raising her hand to his lips. Gradually she became composed. "Do you love me, knight?" she said. Guntram swore that he did, with many passionate avowals, and the lady slipped a ring on his finger. Even as he embraced her the cry of a screech-owl rang through the night air, and the maiden became a corpse in his arms. Overcome with terror, he staggered through the darkness to his room, where he sank down unconscious.

[paragraph continues] On coming to himself again, he thought for a moment that the experience must have been a dream, but the ring on his hand assured him that the vision was a ghastly reality. He attempted to remove the gruesome token, but he found to his horror that it seemed to have grown to his finger.

In the morning he related his experience to the attendant. "Alas, alas!" said the old man, "in three times nine days you must die."

Guntram was quite overcome by the horror of his situation, and seemed for a time bereft of his senses. Then he had his horse saddled, and galloped as hard as he was able to Falkenburg. Liba greeted him solicitously. She could see that he was sorely troubled, but forbore to question him, preferring to wait until he should confide in her of his own accord. He was anxious that their wedding should be hastened, for he thought that his union with the virtuous Liba might break the dreadful spell.

When at length the wedding day arrived everything seemed propitious, and there was nothing to indicate the misfortune which threatened the bridegroom. The couple approached the altar and the priest joined their hands. Suddenly Guntram fell to the ground, foaming and gasping, and was carried thence to his home. The faithful Liba stayed by his side, and when he had partially recovered the knight told her the story of the spectre, and added that when the priest had joined their hands he had imagined that the ghost had put her cold hand in his. Liba attempted to soothe her repentant lover, and sent for a priest to finish the interrupted wedding ceremony. This concluded, Guntram embraced his wife, received absolution, and expired.

Liba entered a convent, and a few years later she herself passed away, and was buried by the side of her husband.

Bishop Hatto is a figure equally well known to history and tradition, though, curiously enough, receiving a much rougher handling from the latter than the former. History relates that Hatto was Archbishop of Mainz in the tenth century, being the second of his name to occupy that see. As a ruler he was firm, zealous, and upright, if somewhat ambitious and high-handed, and his term of office was marked by a civic peace not always experienced in those times. So much for history. According to tradition, Hatto was a stony-hearted oppressor of the poor, permitting nothing to stand in the way of the attainment of his own selfish ends, and several wild legends exhibit him in a peculiarly unfavourable light.

By far the most popular of these traditions is that which deals with the Mäuseturm, or 'Mouse Tower,' situated on a small island in the Rhine near Bingen. It has never been quite decided whether the name was bestowed because of the legend, or whether the legend arose on account of the name, and it seems at least probable that the tale is of considerably later date than the tenth century. Some authorities regard the word Mäuseturm as a corruption of Mauth-turm, a 'toll-tower,' a probable but prosaic interpretation. Much more interesting is the name 'Mouse Tower,' which gives point to the tragic tale of Bishop Hatto's fate. The story cannot be better told than in the words of Southey, who has immortalized it in the following ballad:

Click to enlarge

THE MOUSE TOWER, NEAR BINGEN

LOUIS WEIRTER, R.B.A.

Facing page 206.

Every day the starving poor

Crowded around Bishop Hatto’s door,

For he had a plentiful last-year’s store,

And all the neighbourhood could tell

His granaries were furnished well.

At last Bishop Hatto appointed a day

To quiet the poor without delay;

He bade them to his great barn repair,

And they should have food for the winter there.

Rejoiced such tidings good to hear,

The poor folk flocked from far and near;

The great barn was full as it could hold

Of women and children, and young and old.

Then when he saw it could hold no more,

Bishop Hatto he made fast the door;

And while for mercy on Christ they call,

He set fire to the barn and burnt them all.

"I’ faith, ’tis an excellent bonfire!" quoth he,

"And the country is greatly obliged to me

For ridding it in these times forlorn

Of rats that only consume the corn."

So then to his palace returnèd he,

And he sat down to supper merrily;

And he slept that night like an innocent man,

But Bishop Hatto never slept again.

In the morning as he enter’d the hall

Where his picture hung against the wall,

A sweat like death all over him came,

For the rats had eaten it out of the frame.

As he looked there came a man from his farm,

He had a countenance white with alarm;

"My lord, I opened your granaries this morn,

And the rats had eaten all your corn." p. 208

Another came running presently,

And he was pale as pale could be;

"Fly, my Lord Bishop, fly!" quoth he,

"Ten thousand rats are coming this way--

The Lord forgive you for yesterday!"

"I’ll go to my tower on the Rhine," replied he,

"’Tis the safest place in Germany;

The walls are high and the shores are steep,

And the stream is strong and the water deep."

Bishop Hatto fearfully hastened away,

And he crossed the Rhine without delay,

And reached his tower, and barred with care

All windows, doors, and loop-holes there.

He laid him down and closed his eyes;--

But soon a scream made him arise,

He started and saw two eyes of flame

On his pillow from whence the screaming came.

He listened and looked--it was only the cat;

But the Bishop he grew more fearful for that,

For she sat screaming, mad with fear,

At the army of rats that were drawing near.

For they have swum over the river so deep,

And they have climbed the shores so steep,

And up the tower their way is bent,

To do the work for which they were sent.

They are not to be told by the dozen or score,

By thousands they come, and by myriads and more,

Such numbers had never been heard of before,

Such a judgment had never been witnessed of yore.

Down on his knees the Bishop fell,

And faster and faster his beads did he tell,

As louder and louder, drawing near,

The gnawing of their teeth he could hear.

And in at the windows and in at the door,

And through the walls helter-skelter they pour,

And down through the ceiling, and up through the floor,

From the right and the left, from behind and before,

From within and without, from above and below,

And all at once to the Bishop they go. p. 209

They have whetted their teeth against the stones,

And now they pick the Bishop’s bones;

They gnawed the flesh from every limb,

For they were sent to do judgment on him.

Many other tales are told to illustrate Hatto's cruelty and treachery. Facing the Mouse Tower, on the opposite bank of the Rhine, stands the castle of Ehrenfels, the scene of another of his ignoble deeds.

Conrad, brother of the Emperor Ludwig, had, it is said, been seized and imprisoned in Ehrenfels by the Franconian lord of that tower, Adalbert by name. It was the fortune of war, and Ludwig in turn gathered a small force and hastened to his brother's assistance. His attempts to storm the castle, however, were vain; the stronghold and its garrison stood firm. Ludwig was minded to give up the struggle for the time being, and would have done so, indeed, but for the intervention of his friend and adviser, Bishop Hatto.

"Leave him to me," said the crafty Churchman. "I know how to deal with him."

Ludwig was curious to know how his adviser proposed to get the better of Adalbert, whom he knew of old to be a man of courage and resource, but ill-disposed toward the reigning monarch. So the Bishop unfolded his scheme, to which Ludwig, with whom honour was not an outstanding feature, gave his entire approval.

In pursuance of his design Hatto sallied forth unattended, and made his way to the beleaguered fortress. Adalbert, himself a stranger to cunning and trickery, hastened to admit the messenger, whose garb showed him to be a priest, thinking him bound on an errand of peace. Hatto

professed the deepest sorrow at the quarrel between Ludwig and Adalbert.

"My son," said he solemnly, "it is not meet that you and the Emperor, who once were friends, should treat each other as enemies. Our sire is ready to forgive you for the sake of old friendship; will you not give him the opportunity and come with me?"

Adalbert was entirely deceived by the seeming sincerity of the Bishop, and so touched by the clemency of the sovereign that he promised to go in person and make submission if Hatto would but guarantee his safety.

The conversation was held in the Count's oratory, and the Churchman knelt before the crucifix and swore in the most solemn manner that he would bring Adalbert safely back to his castle.

In a very short time they were riding together on the road to Mainz, where Ludwig held court. When they were a mile or two from Ehrenfels Hatto burst into a loud laugh, and in answer to the Count's questioning glance he said merrily:

"What a perfect host you are! You let your guest depart without even asking him whether he has breakfasted. And I am famishing, I assure you!"

The courteous Adalbert was stricken with remorse, and murmured profuse apologies to his guest. "You must think but poorly of my hospitality," said he; "in my loyalty I forgot my duty as a host."

"It is no matter," said Hatto, still laughing. "But since we have come but a little way, would it not be better to return to Ehrenfels and breakfast? You are young and strong, but I------"

"With pleasure," replied the Count, and soon they were again within the castle enjoying a hearty meal. With her

own hands the young Countess presented a beaker of wine to the guest, and he, ere quaffing it, cried gaily to Adalbert:

"Your health! May you have the reward I wish for you!"

Once again they set out on their journey, and reached Mainz about nightfall. That very night Adalbert was seized ignominiously and dragged before the Emperor. By Ludwig's side stood the false Bishop.

"What means this outrage?" cried the Count, looking from one to the other.

"Thou art a traitor," said Ludwig, "and must suffer the death of a traitor."

Adalbert addressed himself to the Bishop.

"And thou," he said, "thou gavest me thine oath that thou wouldst bring me in safety to Ehrenfels."

"And did I not do so, fool?" replied Hatto contemptuously. "Was it my fault if thou didst not exact a pledge ere we set out for the second time?"

Adalbert saw now the trap into which he had fallen, and his fettered limbs trembled with anger against the crafty priest. But he was impotent.

"Away with him to the block!" said the Emperor.

"Amen," sneered Hatto, still chuckling over the success of his strategy.

And so Adalbert went forth to his doom, the victim of the cruel Churchman's treachery.

Rheingrafenstein, perched upon its sable foundations of porphyry, is the scene of a legend which tells of a terrible bargain with Satan--that theme so frequent in German folk-tale.

A certain nobleman, regarding the site as impregnable

and therefore highly desirable, resolved to raise a castle upon the lofty eminence, But the more he considered the plan the more numerous appeared the difficulties in the way of its consummation.

Every pro and con was carefully argued, but to no avail. At last in desperation the nobleman implored assistance from the Enemy of Mankind, who, hearing his name invoked, and scenting the possibility of gaining a recruit to the hosts of Tartarus, speedily manifested his presence, promising to build the castle in one night if the nobleman would grant him the first living creature who should look from its windows. To this the nobleman agreed, and upon the following day found the castle awaiting his possession. He did not dare to enter it, however. But he had communicated his secret to his wife, who decided to circumvent the Evil One by the exercise of her woman's wit. Mounting her donkey, she rode into the castle, bidding all her men follow her. Satan waited on the alert. But the Countess amid great laughter pinned a kerchief upon the ass's head, covered it with a cap, and, leading it to the window, made it thrust its head outside.

Satan immediately pounced upon what he believed to be his lawful prey, and with joy in his heart seized upon and carried off the struggling beast of burden. But the donkey emitted such a bray that, recognizing the nature of his prize, the Fiend in sheer disgust dropped it and vanished in a sulphurous cloud, to the accompaniment of inextinguishable laughter from Rheingrafenstein.

The town of Rüdesheim is a place famous in song and story, and some of the legends connected with it date from almost prehistoric times. Passing by in the steamer, the

Click to enlarge

RHEINGRAFENSTEIN

LOUIS WEIRTER, R.B.A.

Facing page 212.

traveller who cares for architecture will doubtless be surprised to mark an old church which would seem to be at least partly of Norman origin; but this is not the only French association which Rüdesheim boasts, for Charlemagne, it is said, loved the place and frequently resided there, while tradition even asserts that he it was who instituted the vine-growing industry on the adjacent hills. He perceived that whenever snow fell there it melted with amazing rapidity; and, judging from this that the soil was eminently suitable for bringing forth a specially fine quality of grape, he sent to France for a few young vine plants. Soon these were thriving in a manner which fully justified expectations. The wines of Rüdesheim became exceptionally famous; and, till comparatively recent times, one of the finest blends was always known as Wein von Orleans, for it was thence that the pristine cuttings had been imported.

But it need scarcely be said, perhaps, that most of the legends current at Rüdesheim are not concerned with so essentially pacific an affair as the production of Rhenish. Another story of the place relates how one of its medieval noblemen, Hans, Graf von Brauser, having gone to Palestine with a band of Crusaders, was taken prisoner by the Saracens; and during the period of his captivity he vowed that, should he ever regain his liberty, he would signify his pious gratitude by causing his only daughter, Minna, to take the veil. Rather a selfish kind of piety this appears! Yet mayhap Hans was really devoted to his daughter, and his resolution to part with her possibly entailed a heart-rending sacrifice; while, be that as it may, he had the reward he sought, for now his prison was stormed and he himself released, whereupon he hastened back to his home at Rüdesheim with intent to fulfil his

promise to God. On reaching his schloss, however, Graf Hans was confronted by a state of affairs which had not entered into his calculations, the fact being that in the interim his daughter had conceived an affection for a young nobleman called Walther, and had promised to marry him at an early date. Here, then, was a complication indeed, and Hans was sorely puzzled to know how to act, while the unfortunate Minna was equally perplexed, and for many weeks she endured literal torment, her heart being racked by a constant storm of emotions. She was deeply attached to Walther, and she felt that she would never be able to forgive herself if she broke her promise to him and failed to bring him the happiness which both were confident their marriage would produce; but, on the other hand, being of a religious disposition, she perforce respected the vow her father had made, and thought that if it were broken he and all his household would be doomed to eternal damnation, while even Walther might be involved in their ruin. "Shall I make him happy in this world only that he may lose his soul in the next?" she argued; while again and again her father reminded her that a promise to God was of more moment than a promise to man, and he implored her to hasten to the nearest convent and retire behind its walls. Still she wavered, however, and still her father pleaded with her, sometimes actually threatening to exert his parental authority. One evening, driven to despair, Minna sought to cool her throbbing pulses by a walk on the wind-swept heights overlooking the Rhine at Rüdesheim. Possibly she would be able to come to a decision there, she thought; but no! she could not bring herself to renounce her lover, and with a cry of despair she flung herself over the steep rocks into the swirling stream.

A hideous death it was. The maiden was immolated on the altar of superstition, and the people of Rüdesheim were awestruck as they thought of the pathetic form drifting down the river. Nor did posterity fail to remember the story, and down to recent times the boatmen of the neighbourhood, when seeing the Rhine wax stormy at the place where Minna was drowned, were wont to whisper that her soul was walking abroad, and that the maiden was once again wrestling with the conflicting emotions which had broken her heart long ago.

Knight Brömser of Rüdesheim was one of those who renounced comfort and home ties to throw in his lot with the Crusaders. He was a widower, and possessed a beautiful daughter, Gisela. In the holy wars in Palestine Brömser soon became distinguished for his bravery, and enterprises requiring wit and prowess often were entrusted to him.

Now it befell that the Christian camp was thrown into consternation by the appearance of a huge dragon which took up its abode in the mountainous country, the only locality whence water could be procured, and the increasing scarcity of the supply necessitated the extirpation of the monster. The Crusaders were powerless through fear; many of them regarded the dragon as a punishment sent from Heaven because of the discord and rivalry which divided them.

At last the brave Brömser offered to attempt the dragon's destruction, and after a valiant struggle he succeeded in slaying it. On his way back to the camp he was surprised by a party of Saracens, and after various hardships was cast into a dungeon. Here he remained in misery for a

long while, and during his solitary confinement he made a vow that if he ever returned to his native land he would found a convent and dedicate his daughter as its first nun.

Some time later the Saracens' stronghold was attacked by Christians and the knight set free. In due course he returned to Rüdesheim, where he was welcomed by Gisela, and the day after his arrival a young knight named Kurt of Falkenstein begged him for her hand. Gisela avowed her love for Kurt, and Brömser sadly replied that he would willingly accede to the young people's wishes, for Falkenstein's father was his companion-in-arms, were he not bound by a solemn vow to dedicate his daughter to the Church. When Falkenstein at last understood that the knight's decision was irrevocable he galloped off as if crazed. The knight's vow, however, was not to be fulfilled; Gisela's reason became unhinged, she wandered aimlessly through the corridors of the castle, and one dark and stormy night cast herself into the Rhine and was drowned. Brömser built the convent, but in vain did he strive to free his conscience from remorse. Many were his benefactions, and he built a church on the spot where one of his servants found a wooden figure of the Crucified, which was credited with miraculous powers of healing. But all to no purpose. Haunted by the accusing spirit of his unfortunate daughter, he gradually languished and at last died in the same year that the church was completed.

Further up the river is Oestrich, adjacent to which stood the famous convent of Gottesthal, not a vestige of which remains to mark its former site. Its memory is preserved, however, in the following appalling legend, the noble referred to being the head of one of the ancient families of the neighbourhood.

Among the inmates of Gottesthal was a nun of surpassing loveliness, whose beauty had aroused the wild passion of a certain noble. Undeterred by the fact of the lady being a cloistered nun, he found a way of communicating his passion to her, and at last met her face to face, despite bars and bolts. Eloquently he pleaded his love, swearing to free her from her bonds, to devote his life to her if only she would listen to his entreaties. He ended his asseverations by kneeling before the statue of the Virgin, vowing in her name and that of the Holy Babe to be true, and renouncing his hopes of Heaven if he should fail in the least of his promises. The nun listened and in the end, overcome by his fervour, consented to his wishes.

So one night, under cover of the darkness, she stole from the sheltering convent, forgetting her vows in the arms of her lover. Then for a while she knew a guilty happiness, but even this was of short duration, for the knight soon tired and grew cold toward her. At length she was left alone, scorned and sorrowful, a prey to misery, while her betrayer rode off in search of other loves and gaieties, spreading abroad as he went the story of his conquest and his desertion.

When the injured woman learned the true character of her lover her love changed to a frenzied hate. Her whole being became absorbed in a desire for revenge, her thoughts by day being occupied by schemes for compassing his death, her dreams by night being reddened by his blood. At last she plotted with a band of ruffians, promising them great rewards if they would assassinate her enemy. They agreed and, waylaying the noble, stabbed him fatally in the name of the woman he had

wronged and slighted, then, carrying the hacked body into the village church, they flung it at the foot of the altar.

That night the nun, in a passion of insensate fury, stole into the holy place. Down the length of the church she dragged her lover's corpse, and out into the graveyard, tearing open his body and plucking his heart therefrom with a fell purpose that never wavered. With a shriek she flung it on the ground and trampled upon it in a ruthlessness of hate terrible to contemplate.

And the legend goes on to tell that after her death she still pursued her lover with unquenchable hatred. It is said that when the midnight bell is tolling she may yet be seen seeking his tomb, from which she lifts a bloody heart. She gazes on it with eyes aflame, then, laughing with hellish glee, flings it three times toward the skies, only to let it fall to earth, where she treads it beneath her feet, while from her thick white veil runnels of blood pour down and all around dreary death-lights burn and shed a ghastly glow upon the awful spectre.

Among the multitude of legends which surround the name of Charlemagne there can hardly be found a quainter or more interesting one than that which has for a background the old town of Ingelheim (Angel's Home), where at one time the Emperor held his court.

It is said that one night when Charlemagne had retired to rest he was disturbed by a curious dream. In his vision he saw an angel descend on broad white pinions to his bedside, and the heavenly visitant bade him in the name of the Lord go forth and steal some of his neighbour's goods. The angel warned him ere he departed that the

speedy forfeiture of throne and life would be the penalty for disregarding the divine injunction.

The astonished Emperor pondered the strange message, but finally decided that it was but a dream, and he turned on his side to finish his interrupted slumbers. Scarcely had he closed his eyelids, however, ere the divine messenger was again at his side, exhorting him in still stronger terms to go forth and steal ere the night passed, and threatening him this time with the loss of his soul if he failed to obey.

When the angel again disappeared the trembling monarch raised himself in bed, sorely troubled at the difficulty of his situation. That he, so rich, so powerful that he wanted for nothing, should be asked to go out in the dead of night and steal his neighbour's goods, like any of the common robbers whom he was wont to punish so severely! No! the thing was preposterous. Some fiend had appeared in angelic form to tempt him. And again his weary head sank in his pillow. Rest, however, was denied him. For a third time the majestic being appeared, and in tones still more stern demanded his obedience.

"If thou be not a thief," said he, "ere yonder moon sinks in the west, then art thou lost, body and soul, for ever."

The Emperor could no longer disbelieve the divine nature of the message, and he arose sadly, dressed himself in full armour, and took up his sword and shield, his spear and hunting-knife. Stealthily he quitted his chamber, fearing every moment to be discovered. He imagined himself being detected by his own court in the act of privily leaving his own palace, as though he were a robber, and the thought was intolerable. But his fears were unfounded; all--warders, porters, pages, grooms, yea,

the very dogs and horses--were wrapped in a profound slumber. Confirmed in his determination by this miracle--for it could be nothing less--the Emperor saddled his favourite horse, which alone remained awake, and set out on his quest.

It was a beautiful night in late autumn. The moon hung like a silver shield in the deep blue arch of the sky, casting weird shadows on the slopes and lighting the gloom of the ancient forests. But Charlemagne had no eye for scenery at the moment. He was filled with grief and shame when he thought of his mission, yet he dared not turn aside from it. To add to his misery, he was unacquainted with the technicalities of the profession thus thrust upon him, and did not quite know how to set about it.

For the first time in his life, too, he began to sympathize with the robbers he had outlawed and persecuted, and to understand the risks and perils of their life. Nevermore, he vowed, would he hang a man for a trifling inroad upon his neighbour's property.

As he thus pursued his reflections a knight, clad from head to foot in coal-black armour and mounted on a black steed, issued silently from a clump of trees and rode unseen beside him.

Charlemagne continued to meditate upon the dangers and misfortunes of a robber's life.

"There is Elbegast," said he to himself; "for a small offence I have deprived him of land and fee, and have hunted him like an animal. He and his knights risk their lives for every meal. He respects not the cloth of the Church, it is true, yet methinks he is a noble fellow, for he robs not the poor or the pilgrim, but rather enriches them with part of his plunder. Would he were with me now!"

[paragraph continues] His reflections were suddenly stopped, for he now observed the black knight riding by his side.

"It may be the Fiend," said Charlemagne to himself, spurring his steed.

But though he rode faster and faster, his strange companion kept pace with him. At length the Emperor reined in his steed, and demanded to know who the stranger might be. The black knight refused to answer his questions, and the two thereupon engaged in furious combat. Again and again the onslaught was renewed, till at last Charlemagne succeeded in cleaving his opponent's blade.

"My life is yours," said the black knight.

"Nay," replied the monarch, "what would I with your life? Tell me who you are, for you have fought gallantly this night."

The stranger drew himself up and replied with simple dignity, "I am Elbegast."

Charlemagne was delighted at thus having his wish fulfilled. He refused to divulge his name, but intimated that he, too, was a robber, and proposed that they should join forces for the night.

"I have it," said he. "We will rob the Emperor's treasury. I think I could show you the way."

The black knight paused. "Never yet," he said, "have I wronged the Emperor, and I shall not do so now. But at no great distance stands the castle of Eggerich von Eggermond, brother-in-law to the Emperor. He has persecuted the poor and betrayed the innocent to death. If he could, he would take the life of the Emperor himself, to whom he owes all. Let us repair thither."

Near their destination they tied their horses to a tree and strode across the fields. On the way Charlemagne wrenched

off the iron share from a plough, remarking that it would be an excellent tool wherewith to bore a hole in the castle wall--a remark which his comrade received in silence, though not without surprise. When they arrived at the castle Elbegast seemed anxious to see the ploughshare at work, for he begged Charlemagne to begin operations.

"I know not how to find entrance," said the latter.

"Let us make a hole in the wall," the robber-knight suggested, producing a boring instrument of great strength. The Emperor gallantly set to work with his ploughshare, though, as the wall was ten feet thick, it is hardly surprising that he was not successful. The robber, laughing at his comrade's inexperience, showed him a wide chasm which his boring instrument had made, and bade him remain there while he fetched the spoil. In a very short time he returned with as much plunder as he could carry.

"Let us get away," said the Emperor. "We can carry no more."

"Nay," said Elbegast, "but I would return, with your permission. In the chamber occupied by Eggerich and his wife there is a wonderful caparison, made of gold and covered with little bells. I want to prove my skill by carrying it off."

"As you will," was Charlemagne's laughing response.

Without a sound Elbegast reached the bedchamber of his victim, and was about to raise the caparison when he suddenly stumbled and all the bells rang out clearly.

"My sword, my sword!" cried Eggerich, springing up, while Elbegast sank back into the shadows.

"Nay," said the lady, trying to calm her husband. "You did but hear the wind, or perhaps it was an evil dream. Thou hast had many evil dreams of late, Eggerich;

methinks there is something lies heavily on thy mind. Wilt thou not tell thy wife?"

Elbegast listened intently while with soft words and caresses the lady strove to win her husband's secret.

"Well," said Eggerich at last in sullen tones, "we have laid a plot, my comrades and I. To-morrow we go to Ingelheim, and ere noon Charlemagne shall be slain and his lands divided among us."

"What!" shrieked the lady. "Murder my brother! That will you never while I have strength to warn him." But the villain, with a brutal oath, struck her so fiercely in the face that the blood gushed out, and she sank back unconscious.

The robber was not in a position to avenge the cruel act, but he crawled nearer the couch and caught some of the blood in his gauntlet, for a sign to the Emperor. When he was once more outside the castle he told his companion all that had passed and made as though to return.

"I will strike off his head," said he. "The Emperor is no friend of mine, but I love him still."

"What is the Emperor to us?" cried Charlemagne. "Are you mad that you risk our lives for the Emperor?" The black knight looked at him solemnly.

"An we had not sworn friendship," said he, "your life should pay for these words. Long live the Emperor!" Charlemagne, secretly delighted with the loyalty of the outlawed knight, recommended him to seek the Emperor on the morrow and warn him of his danger. But Elbegast, fearing the gallows, would not consent to this; so his companion promised to do it in his stead and meet him afterward in the forest. With that they parted, the Emperor returning to his palace, where he found all as he had left it.

In the morning he hastily summoned his council, told them of his dream and subsequent adventures, and of the plot against his life. The paladins were filled with horror and indignation, and Charlemagne's secretary suggested that it was time preparations were being made for the reception of the assassins. Each band of traitors as they arrived was seized and cast into a dungeon. Though apparently clad as peaceful citizens, they were all found to be armed. The last band to arrive was led by Eggerich himself. Great was his dismay when he saw his followers led off in chains, and angrily he demanded to know the reason for such treatment.

Charlemagne thereupon charged him with treason, and Eggerich flung down the gauntlet in defiance. It was finally arranged that the Emperor should provide a champion to do battle with the traitor, the combat to take place at sunrise on the following morning.

A messenger rode to summon Elbegast, but he had much difficulty in convincing the black knight that it was not a plot to secure his undoing.

"And what would the Emperor with me?" he demanded of the messenger, as at length they rode toward Ingelheim.

"To do battle to the death with a deadly foe of our lord the Emperor--Eggerich von Eggermond."

"God bless the Emperor!" exclaimed Elbegast fervently, raising his helmet. "My life is at his service." Charlemagne greeted the knight affectionately and asked what he had to tell concerning the conspiracy, whereupon Sir Elbegast fearlessly denounced the villainous Eggerich, and said he, "I am ready to prove my assertions upon his body." The challenge was accepted, and at daybreak the following morning a fierce combat took place. The

issue, however, was never in doubt: Sir Elbegast was victorious, the false Eggerich was slain, and his body hanged on a gibbet fifty feet high. The emperor now revealed himself to the black knight both as his companion-robber and as the messenger who had brought him the summons to attend his Emperor.

Charlemagne's sister, the widow of Eggerich, he gave to Sir Elbegast in marriage, and with her the broad lands which had belonged to the vanquished traitor. Thenceforward the erstwhile robber and his sovereign were fast friends.

The place where these strange happenings befell was called Ingelheim, in memory of the celestial visitor, and Ingelheim it remains to this day.

Elfeld is the principal town of the Rheingau, and in ancient times was a Roman station called Alta Villa. In the fourteenth century it was raised to the rank of a town by Ludwig of Bavaria, and placed under the stewardship of the Counts of Elz.

These Counts of Elz dwelt in the castle by the river's edge, and of one of them, Ferdinand, the following tale is told. This knight loved pleasure and wild living, and would indulge his whims and passions without regard to cost. Before long he found that as a result of his extravagance his possessions had dwindled away almost to nothing. He knew himself a poor man, yet his desire for pleasure was still unsatisfied. Mortified and angry, he hid himself in the castle of Elz and spent his time lamenting his poverty and cursing his fate. While in this frame of mind the news reached him of a tournament that the Emperor purposed holding in celebration of his wedding. To this were summoned the chivalry and beauty of

[paragraph continues] Germany from far and near, and soon knights and ladies were journeying to take their part in the tourney, the feasting and dancing.

Ferdinand realized that he was precluded from joining his brother nobles and was inconsolable. He became the prey of rage and shame, and at last resolved to end a life condemned to ignominy. So one day he sought a height from which to hurl himself, but ere he could carry out his purpose there appeared before him a dwarf, clad in yellow from top to toe. With a leer and a laugh he looked up at the frantic knight, and asked why the richest noble in the land should be seeking death. Something in the dwarf's tone caused Ferdinand to listen and suddenly to hope for he knew not what miracle. His eyes gleamed as the dwarf went on to speak of sacks of gold, and when the little creature asked for but a single hair in return he laughed aloud and offered him a hundred. But the dwarf smiled and shook his head. The noble bowed with a polite gesture, and as he bent his head the little man reached up and plucked out but one hair, and, lo! a sack of gold straightway appeared. At this Ferdinand thought that he must be dreaming, but the sack and gold pieces were real enough to the touch, albeit the dwarf had vanished. Then, in great haste, Ferdinand bought rich and costly clothing and armour, also a snow-white steed caparisoned with steel and purple trappings, spending on these more than twenty sacks of gold, for the dwarf returned to the noble many times and on each occasion gave a sack of gold in exchange for one hair. At last Ferdinand set out for the tournament, where, besides carrying off the richest prizes and winning the heart of many a fair lady, he attracted the notice of the Emperor, who invited him to stay at his court.

And there the knight resumed his former passions and pleasures, living the wildest of lives and thinking no price too high for careless enjoyment. And each night, ere the hour of twelve finished striking, the yellow dwarf appeared with a sack of gold, taking his usual payment of only one hair. This wild life now began to tell upon Ferdinand. He fell an easy prey to disease, which the doctors could not cure, and to the pricks of a late-roused conscience, which no priests could soothe. All his wasted past rose before him. Day and night his manifold sins appeared before him like avenging furies, until at last, frenzied by this double torture of mind and body, he called upon the Devil to aid him in putting an end to his miserable existence, for so helpless was he, he could neither reach nor use a weapon. Then at his side appeared once more the dwarf, smiling and obliging as usual. He proffered, not a sack of gold this time, but a rope of woven hair, the hair which he had taken from Ferdinand in exchange for his gold. In the morning the miserable noble was found hanging by that rope.

Mainz, the old Maguntiacum, was the principal fortress on the Upper Rhine in Roman times. It was here that Crescentius, one of the first preachers of the Christian faith on the Rhine, regarded by local tradition as the pupil of St. Peter and first Archbishop of Mainz, suffered martyrdom in the reign of Trajan in A.D. 103. He was a centurion in the Twenty-second Legion, which had been engaged under Titus in the destruction of Jerusalem, and it is supposed that he preached the Gospel in Mainz for thirty-three years before his execution. Here also it was that the famous vision of Constantine, the cross in the sky, was vouchsafed to the

[paragraph continues] Christian conqueror as he went forth to meet the forces of Maxentius. The field of the Holy Cross in the vicinity of Mainz is still pointed out as the spot where this miracle took place. The city flourished under the Carlovingians, and was in a high state of prosperity at the time of Bishop Hatto, whose name, as we have seen, has been held up to obloquy in many legends.

During the fourteenth century Mainz shared the power and glory of the other cities of the Rhenish Confederation, then in the full flush of its heyday. Its cathedral witnesses to its aforetime civic splendour. This magnificent building took upward of four hundred years to complete, and its wondrous brazen doors and sumptuous chapels are among the finest ecclesiastical treasures of Germany.

In the cathedral of Mainz was an image of the Virgin, on whose feet were golden slippers, the gift of some wealthy votary. Of this image the following legend is told:

A poor ragged fiddler had spent the whole of one bitter winter morning playing through the dreary streets without any taking pity upon his plight. As he came to the cathedral he felt an overmastering desire to enter and pour out his distress in the presence of his Maker. So he crept in, a tattered and forlorn figure. He prayed aloud, chanting his woes in the same tones which he used in the street to touch the hearts of the passers-by.

As he prayed a sense of solitude came upon him, and he realized that the shadowy aisles were empty. A sudden whim seized him. He would play to the golden-shod Virgin and sing her one of his sweetest songs. And drawing nearer he lifted his old fiddle to his shoulder, and into his playing he put all his longing and pain; his

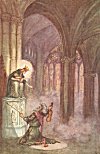

Click to enlarge

The Fiddler and the Statue 228

Hiram Ellis.

quavering voice grew stronger beneath the stress of his fervour. It was as if the springtime had come about him; life was before him, gay and joyful, sorrow and pain were unknown. He sank to his knees before the image, and as he knelt, suddenly the Virgin lifted her foot and, loosening her golden slipper, cast it into the old man's ragged bosom, as if giving alms for his music.

The poor old man, astounded at the miracle, told himself that the Blessed Virgin knew how to pay a poor devil who amused her. Overcome by gratitude, he thanked the giver with all his heart.

He would fain have kept the treasure, but he was starving, and it seemed to have been given him to relieve his distress. He hurried out to the market and went into a goldsmith's shop to offer his prize. But the man recognized it at once. Then was the poor old fiddler worse off than before, for now he was charged with the dreadful crime of sacrilege. The old man told the story of the miracle over and over again, but he was laughed at for an impudent liar. He must not hope, they told him, for anything but death, and in the short space of one hour he was tried and condemned and on his way to execution.

The place of death was just opposite the great bronze doors of the cathedral which sheltered the Virgin. "If I must die," said the fiddler, "I would sing one song to my old fiddle at the feet of the Virgin and pray one prayer before her. I ask this in her blessed name, and you cannot refuse me."

They could not deny the prisoner a dying prayer, and, closely guarded, the tattered figure once more entered the cathedral which had been so disastrous to him. He approached the altar of the Virgin, his eyes filling with tears as again he held his old fiddle in his hands. Then he

played and sang as before, and again a breath as of springtime stole into the shadowy cathedral and life seemed glad and beautiful. When the music ceased, again the Virgin lifted a foot and softly she flung her other slipper into the fiddler's bosom, before the astonished gaze of the guards. Everyone there saw the miracle and could not but testify to the truth of the old man's former statement; he was at once freed from his bonds and carried before the city fathers, who ordered his release.

And it is said that, in memory of the miracle of the Virgin, the priests provided for the old fiddler for the rest of his days. In return for this the old man surrendered the golden slippers, which, it is also said, the reverend fathers carefully locked away in the treasure-chest, lest the Virgin should again be tempted to such extravagant almsgiving.

Once in the Hardt mountains there dwelt a giant whose fortress commanded a wide view of the surrounding country. Near by, a lovely lady, as daring in the hunt as she was skilful at spinning, inhabited an abandoned castle. One day the twain chanced to meet, and the giant thereupon resolved to possess the beauteous damsel.

So he sent his servant to win her with jewels, but the deceitful fellow intended to hide the treasures in a forest.

There he met a young man musing in a disconsolate attitude, who confided that poverty alone kept him from avowing how passionately he adored his sweetheart. The shrewd messenger realized that this rustic's charmer was the same fair lady who had beguiled his master's soul. He solicited the youth's aid in burying the treasures

promising him a share in the spoil sufficient to enable him to wed his beloved.

In a solitary spot they dug a deep hole, when suddenly the robber assailed his companion, who thrust him aside with great violence. In his rage the youth was about to stab the wretch, when he craved pardon, promising to reveal a secret of more value than the jewels he had intended to conceal.

The youth stayed his hand, and the servant related how his master, for love of the pretty mistress of the castle, had sent him to gain her favour.

Conscious of his worth, the ardent youth scornfully declared that he feared no rival, then, seizing half of the treasure, he left the wretch to his own devices.

Meanwhile the giant impatiently awaited his servant's return. At length, tired of waiting, he decided to visit the lady and declare in person his passion for her. Upon his arrival at the castle the maid announced him, and it was with a secret feeling of dread that the lady went to meet her unwelcome visitor. More than ever captivated by her charms, the giant asked the fair maid to become his wife. On being refused, he threatened to kill her and demolish the castle.

The poor lady was terrified and she tearfully implored the giant's mercy, promising to bestow all her treasure upon him. Her maids, too, begged him to spare their mistress's life, but he only laughed as they knelt before him. Ultimately the hapless maiden consented to marry her inexorable wooer, but she attached a novel condition: she would ride a race with her relentless suitor, and should he overtake her she would accompany him to his castle. But the resolute maiden had secretly vowed to die rather than submit to such degradation. Choosing her fleetest

steed, she vaulted nimbly into the saddle and galloped away. Her persecutor pursued close behind, straining every nerve to come up with her. Shuddering at the very thought of becoming his bride, she chose death as the only alternative. So she spurred her horse onward to the edge of a deep chasm.

The noble animal neighed loudly as though conscious of impending danger. The pursuer laughed grimly as he thought to seize his prize, but his laughter was turned to rage when the horse with its fair burden bounded lightly across the chasm, landing safely on the other side.

The enraged tyrant now beheld his intended victim kneeling in prayer and her steed calmly grazing among the green verdure by her side. He strode furiously hither and thither, searching for a crossing, and suddenly a shout of joy told the affrighted maid that he had discovered some passage.

His satisfaction, however, was short-lived, for just then a strange knight with drawn sword rushed upon the giant. The maid watched the contest with breathless fear, and many times she thought that the tyrant would slay her protector. At last in one such moment the giant stooped to clutch a huge boulder with which he meant to overwhelm his adversary, when, overreaching himself, he slipped and fell headlong down the steep rocks.

Then the maid hastened to thank her rescuer, and great was her surprise to discover in the gallant knight the youth whose former poverty had kept him from wooing her. They returned to the castle together, and it was not long ere they celebrated their wedding.

Both lived long and happily, and their union was blessed with many children. The rock is still known as "The Maiden's Leap."

Near Homburg, on the pinnacle of a lofty mountain, are the ruins of Falkenstein Castle, access to which is gained by a steep, winding path.

Within the castle walls there once dwelt a maiden of surpassing beauty. Many suitors climbed the stern acclivity to woo this charming damsel, but her stern father repelled one and all. Only Kuno of Sayn was firm enough to persevere in his suit against the rebuffs of the stubborn Lord of Falkenstein, and in the end he was rewarded with the smiles and kind looks of the fair maid.

One evening, as they watched the sun set, Kuno pointed out to the maiden where his own castle was situated. The beauty of the landscape beneath them made its appeal to their souls, their hands touched and clasped, and their hearts throbbed with the passion felt by both. A few days later Kuno climbed the steep path, resolved to declare his love to the damsel's father. Fatigued with the ascent, he rested for a brief space at the entrance to the castle ere mounting to the tower.

The Lord of Falkenstein and his daughter had beheld Kuno's journey up the rugged path from the windows of the tower, and the father demanded for what purpose he had come thither. With a passionate glance at the blushing maid, the knight of Sayn declared that he had come to ask the noble lord for his daughter's hand in marriage. After meditating on the knight's proposal for some time, the Lord of Falkenstein pretended to be willing to give his consent--but he attached a condition. "I desire a carriage-drive to be made from the lowland beneath to the gate of my castle, and if you can accomplish

this my daughter's hand is yours--but the feat must be achieved by to-morrow morning!"

The knight protested that such a task was utterly impossible for anyone to perform, even in a month, but all to no purpose. He then resolved to seek some way whereby he could outwit the stubborn lord, for he would not willingly resign his lady-love. He left the tower, vowing to do his utmost to perform the seemingly impossible task, and as he descended the rocky declivity his beloved waved her handkerchief to encourage him.

Now Kuno of Sayn possessed both copper and silver mines, and arriving at his castle he summoned his overseer. The knight explained the nature of the task which he desired to be undertaken, but the overseer declared that all his miners, working day and night, could not make the roadway within many months.

Dismayed, Kuno left his castle and wandered into a dense forest, driven thither by his perturbed condition. Night cast dusky shadows over the foliage, and the perplexed lover cursed the obstinate Lord of Falkenstein as he forced his way through the undergrowth.

Suddenly an old man of strange and wild appearance stood in his path. Kuno at once knew him for an earth-spirit, one of those mysterious guardians of the treasures of the soil who are jealous of the incursion of mankind into their domain.

"Kuno of Sayn," he said, "do you desire to outwit the Lord of Falkenstein and win his beauteous daughter?"

Although startled and taken aback by the strange apparition, Kuno hearkened eagerly to its words as showing an avenue of escape from the dilemma in which he found himself.

"Assuredly I do," he replied, "but how do you propose I should accomplish it?"

"Cease to persecute me and my brethren, Kuno, and we shall help you to realize your wishes," was the reply.

"Persecute you!" exclaimed Kuno. "In what manner do I trouble you at all, strange being?"

"You have opened up a silver mine in our domain," said the earth-spirit, "and as you work it both morning and afternoon we have but little opportunity for repose. How, I ask you, can we slumber when your men keep knocking on the partitions of our house with their picks?"

"What, then, would you have, my worthy friend?" asked Kuno, scarcely able to suppress a smile at the wistful way in which the gnome made his complaint. "Tell me, I pray you, how I can oblige you."

"By instructing your miners to work in the mine during the hours of morning only," replied the gnome. "By so doing I and my brothers will obtain the rest we so much require."

"It shall be as you say," said Kuno; "you have my word for it, good friend."

"In that case," said the earth-spirit, "we shall assist you in turn. Go to the castle of Falkenstein after dawn to-morrow morning, and you shall witness the result of our friendship and gratitude."

Next morning the sun had scarcely risen when Kuno saddled his steed and hied him to the heights of Falkenstein. The gnome had kept his word. There, above and in front of him, he beheld a wide and lofty roadway leading to the castle-gate from the thoroughfare below. With joy in his heart he set spurs to his horse and dashed up the steep but smooth acclivity. At the gate he encountered the old Lord of Falkenstein and his daughter, who had

been apprised of the miracle that had happened and had come out to view the new roadway. The knight of Sayn related his adventure with the earth-spirit, upon which the Lord of Falkenstein told him how a terrible thunderstorm mingled with unearthly noises had raged throughout the night. Terrified, he and his daughter had spent the hours of darkness in prayer, until with the approach of dawn some of the servitors had plucked up courage and ventured forth, when the wonderful avenue up the side of the mountain met their startled gaze.

Kuno and his lady-love were duly united. Indeed, so terrified was the old lord by the supernatural manifestations of the dreadful night he had just passed through that he was incapable of further resistance to the wishes of the young people. The wonderful road is still to be seen, and is marvelled at by all who pass that way.

Other tales besides the foregoing have their scene laid in the castle of Falkenstein, notable among them being the legend of Osric the Lion, embodied in the following weird ballad from the pen of Monk Lewis:

No longer resound through the vaults of yon hall

The song of the minstrel, and mirth of the ball;

Those pleasures for ever are fled:

There now dwells the bat with her light-shunning brood,

There ravens and vultures now clamour for food,

And all is dark, silent, and dread! p. 237

Ha! dost thou not see, by the moon's trembling light

Directing his steps, where advances a knight,

His eye big with vengeance and fate?

’Tis Osric the Lion his nephew who leads,

And swift up the crackling old staircase proceeds,

Gains the hall, and quick closes the gate.

Now round him young Carloman, casting his eyes,

Surveys the sad scene with dismay and surprise,

And fear steals the rose from his cheeks.

His spirits forsake him, his courage is flown;

The hand of Sir Osric he clasps in his own,

And while his voice falters he speaks.

"Dear uncle," he murmurs, "why linger we here?

’Tis late, and these chambers are damp and are drear,

Keen blows through the ruins the blast!

Oh! let us away and our journey pursue:

Fair Blumenberg's Castle will rise on our view,

Soon as Falkenstein forest be passed.

"Why roll thus your eyeballs? why glare they so wild?

Oh! chide not my weakness, nor frown, that a child

Should view these apartments with dread;

For know that full oft have I heard from my nurse,

There still on this castle has rested a curse,

Since innocent blood here was shed.

"She said, too, bad spirits, and ghosts all in white,

Here used to resort at the dead time of night,

Nor vanish till breaking of day;

And still at their coming is heard the deep tone

Of a bell loud and awful--hark! hark! ’twas a groan!

Good uncle, oh! let us away!"

"Peace, serpent!" thus Osric the Lion replies,

While rage and malignity gleam in his eyes;

"Thy journey and life here must close:

Thy castle's proud turrets no more shalt thou see;

No more betwixt Blumenberg's lordship and me

Shalt thou stand, and my greatness oppose.

"My brother lies breathless on Palestine's plains,

And thou once removed, to his noble domains

My right can no rival deny:

Then, stripling, prepare on my dagger to bleed;

No succour is near, and thy fate is decreed,

Commend thee to Jesus and die!" p. 238

Thus saying, he seizes the boy by the arm,

Whose grief rends the vaulted hall's roof, while alarm

His heart of all fortitude robs;

His limbs sink beneath him; distracted with fears,

He falls at his uncle's feet, bathes them with tears,

And "Spare me! oh, spare me!" he sobs.

But vainly the miscreant he tries to appease;

And vainly he clings in despair round his knees,

And sues in soft accents for life;

Unmoved by his sorrow, unmoved by his prayer,

Fierce Osric has twisted his hand in his hair,

And aims at his bosom a knife.

But ere the steel blushes with blood, strange to tell!

Self-struck, does the tongue of the hollow-toned bell

The presence of midnight declare:

And while with amazement his hair bristles high,

Hears Osric a voice, loud and terrible, cry,

In sounds heart-appalling, "Forbear!"

Straight curses and shrieks through the chamber resound,

Shrieks mingled with laughter; the walls shake around;

The groaning roof threatens to fall;

Loud bellows the thunder, blue lightnings still flash;

The casements they clatter; chains rattle; doors clash,

And flames spread their waves through the hall.

The clamour increases, the portals expand!

O’er the pavement's black marble now rushes a band

Of demons, all dropping with gore,

In visage so grim, and so monstrous in height,

That Carloman screams, as they burst on his sight,

And sinks without sense on the floor.

Not so his fell uncle:--he sees that the throng

Impels, wildly shrieking, a female along,

And well the sad spectre he knows!

The demons with curses her steps onwards urge;

Her shoulders, with whips formed of serpents, they scourge,

And fast from her wounds the blood flows.

"Oh! welcome!" she cried, and her voice spoke despair;

"Oh! welcome, Sir Osric, the torments to share,

Of which thou hast made me the prey.

Twelve years have I languished thy coming to see;

Ulrilda, who perished dishonoured by thee

Now calls thee to anguish away! p. 239

"Thy passion once sated, thy love became hate;

Thy hand gave the draught which consigned me to fate,

Nor thought I death lurked in the bowl:

Unfit for the grave, stained with lust, swelled with pride,

Unblessed, unabsolved, unrepenting, I died,

And demons straight seized on my soul.

"Thou com’st, and with transport I feel my breast swell:

Full long have I suffered the torments of hell,

And now shall its pleasures be mine!

See, see, how the fiends are athirst for thy blood!

Twelve years has my panting heart furnished their food.

Come, wretch, let them feast upon thine!"

She said, and the demons their prey flocked around;

They dashed him, with horrible yell, on the ground,

And blood down his limbs trickled fast;

His eyes from their sockets with fury they tore;

They fed on his entrails, all reeking with gore,

And his heart was Ulrilda's repast.

But now the grey cock told the coming of day!

The fiends with their victim straight vanished away,

And Carloman's heart throbbed again;

With terror recalling the deeds of the night,

He rose, and from Falkenstein speeding his flight,

Soon reached his paternal domain.

Since then, all with horror the ruins behold;

No shepherd, though strayed be a lamb from his fold,

No mother, though lost be her child,

The fugitive dares in these chambers to seek,

Where fiends nightly revel, and guilty ghosts shriek

In accents most fearful and wild!

Oh! shun them, ye pilgrims! though late be the hour,

Though loud howl the tempest, and fast fall the shower;

From Falkenstein Castle begone!

There still their sad banquet hell's denizens share;

There Osric the Lion still raves in despair:

Breathe a prayer for his soul, and pass on!

A legend of later date than most of the Rhineland tales, but still of sufficient interest to merit inclusion among

these, is that which attaches to the palace of Biberich. Biberich lies on the right bank of the river, not very far from Mainz, and its palace was built at the beginning of the eighteenth century by George Augustus, Duke of Nassau.

The legend states that not long after the erection of the palace a Duchess of Nassau died there, and lay in state as befitted her rank in a room hung with black velvet and lighted with the glimmer of many tapers.

Outside in the great hall a captain and forty-nine men of the Duke's bodyguard kept watch over the chamber of death.

It was midnight. The captain of the guard, weary with his vigil, had gone to the door of the palace for a breath of air. Just as the last stroke of the hour died away he beheld the approach of a chariot, drawn by six magnificent coal-black horses, which, to his amazement, drew up before the palace. A lady, veiled and clad in white, alighted and made as though she would enter the building. But the captain barred the way and challenged the bold intruder.

"Who are you," he said sternly, "who seek to enter the palace at this hour? My orders are to let none pass."

"I was first lady of the bedchamber to our late Duchess," replied the lady in cold, imperious tones; "therefore I demand the right of entrance."

As she spoke she flung aside her veil, and the captain, instantly recognizing her, permitted her to enter the palace without further hindrance.

"What can she want here at this time of night?" he said to his lieutenant, when the lady had passed into the death-chamber.

"Who can say?" replied the lieutenant. "Unless, perchance," he mused, "we were to look."

The captain took the hint, crept softly to the keyhole, and applied his eye thereto. "Ha!" he said, shrinking back in amazement and terror, and beckoning to his lieutenant. "In Satan's name what have we here?"

The lieutenant hastened to the chamber door, full of alarm and curiosity. Putting his eye to the keyhole, he also ejaculated, turned pale, and trembled. One by one the soldiers of the guard followed their officers' example, like them to retreat with exclamations of horror. And little wonder; for they perceived the dead Duchess sitting up in bed, moving her pale lips as though in conversation, while by her side stood the lady of the bedchamber, pale as she, and clad in grave-clothes. For a time the ghastly conversation continued, no words being audible to the terror-stricken guard; but from time to time a hollow sound reached them, like the murmur of distant thunder. At length the visitor emerged from the chamber, and returned to her waiting coach. Duty, rather than inclination, obliged the gallant captain to hand her into her carriage, and this task he performed with praiseworthy politeness, though his heart sank within him at the touch of her icy fingers, and his tongue refused to return the adieu her pale lips uttered. With a flourish of whips the chariot set off. Sparks flew from the hoofs of the horses, smoke and flame burst from their nostrils, and such was their speed that in a moment they were lost to sight. The captain, sorely puzzled by the events of the night, returned to his men, who were huddled together at the end of the hall furthest from the death-chamber.

On the morrow, ere the guard had had time to inform the Duke of these strange happenings, news reached the

palace that the first lady of the bedchamber had died on the previous night at twelve o'clock. It was supposed that sorrow for her mistress had caused her death.

Of the castle of Eppstein, whose ruins still remain in a valley of the Taunus Mountains, north of Biberich, the following curious story is told.

Sir Eppo, a brave and chivalrous knight--and a wealthy one to boot, as were his successors of Eppstein for many generations--was one day hunting in the forest, when he became separated from his attendants and lost his way. In the heat of the chase his sense of direction had failed him, and though he sounded his bugle loud and long there was no reply.

Tired out at length with wandering hither and thither, he rested himself in a pleasant glade, and was surprised and charmed to hear a woman's voice singing a mournful melody in soft, clear tones. It was a sheer delight to Sir Eppo to listen to a voice of such exquisite purity, yet admiration was not the only feeling it roused in his breast. There was a note of sadness and appeal in the song, and what were knighthood worth if it heeded not the voice of fair lady in distress? Sir Eppo sprang to his feet, forgetting his own plight in the ardour of chivalry, and set off in the direction from which the voice seemed to come. The way was difficult, and he had to cut a passage with his sword through the dense thicket that separated him from the singer. At length, guided by the melancholy notes, he arrived before a grotto, in which he beheld a maiden of surpassing beauty, but of sorrowful mien. When she saw the handsome knight gazing at her with mingled surprise and admiration she ceased her song and

Click to enlarge

EPPSTEIN

LOUIS WEIRTER, R.B.A.

Facing page 242.

implored his aid. A cruel giant, she said, had seized her and brought her thither. At the moment he was asleep, but he had tied her to a rock so that she might not escape.

Her beauty and grace, her childlike innocence, her piteous plight, moved Sir Eppo strangely. First pity, then a stronger emotion dawned in his breast. He severed her bonds with a stroke of his keen falchion.

"What can I do to aid thee, gentle maiden?" he said. "You have but to command me; henceforth I am thy knight, to do battle for thee."

The damsel blushed at the courteous words, but she lifted her eyes bravely to the champion who had so unexpectedly appeared to protect her.

"Return to my castle," she said, "and there thou wilt find a consecrated net. Bring it hither. If I lay it upon the giant he will become as weak as a babe and will be easily overcome."

Eagerly the young knight obeyed the command, and having found the net according to the damsel's directions, he made all haste to return. At the grotto he paused and hid himself, for the strident voice of the giant could be heard within. Presently the monster emerged, and departed in search of reeds wherewith to make a pipe. No sooner had he disappeared than the maiden issued from the grotto, and Sir Eppo came out of his concealment and gave her the consecrated net. She spoke a few words of heartfelt gratitude, and then hurried with her treasure to the top of the mountain, where she knew the giant had intended to go.

Arrived at her destination, she laid down the net and covered it with moss, leaves, and sweet-smelling herbs. While engaged in her task the giant came up, and the

damsel smilingly told him that she was preparing a couch whereon he might take some rest. Gratified at her solicitude, he stretched himself unsuspectingly on the fragrant pile. In a moment the damsel, uttering the name of the Trinity, threw a portion of the net over him, so that he was completely enveloped. Immediately there arose such loud oaths and lamentations that the damsel ran in terror to the knight, who had now come upon the scene.

"Let us fly," she said, "lest he should escape and pursue us."

But Sir Eppo strode to the place where the howling monster lay entangled in the net, and with a mighty effort rolled him over a steep precipice, where he was instantly killed.

The story ends happily, for Sir Eppo and the maiden he had rescued were married soon after; and on the spot where they had first met was raised the castle of Eppstein. It is said that the bones of the giant may still be seen there.

In the now ruined castle of Wilenstein, overlooking the wooded heights of the Westrich, dwelt Sir Bodo of Flörsheim and his fair daughter Adeline. The maiden's beauty, no less than her father's wealth, attracted suitors in plenty from the neighbouring strongholds, but the spirit of love had not yet awakened in her bosom and each and all were repulsed with disconcerting coldness and indifference, and they left the schloss vowing that the lovely Adeline was utterly heartless.

One day there came to Sir Bodo a youth of pleasing manners and appearance, picturesquely clad in rustic garb, who begged that he might enter the knight's service in

the capacity of shepherd. Though he hinted that he was of noble birth, prevented by circumstances from revealing his identity, yet he based his request solely on his merits as a tender of flocks and herds, and as Sir Bodo found that he knew his work well and that his intelligence was beyond question, he gave him the desired post. As time went on Sir Bodo saw no reason to regret his action, for his flocks and herds prospered as they had never done before, and none but good reports reached him concerning his servant.

Meantime Adeline heard constant references to Otto (as the shepherd was called) both from her father and her waiting-women. The former praised his industry and abilities, while the latter spoke of his handsome looks and melancholy air, his distinction and good breeding, and the mystery which surrounded his identity. All this excited the maiden's curiosity, and her pity was aroused as well, for it seemed that the stranger had a secret grief, which sometimes found vent in tears when he thought himself unobserved.

Adeline saw him for the first time one afternoon while she was walking in the castle grounds. At sight of her he paused as though spell-bound, and the maiden blushed under his earnest scrutiny. A moment later, however, he recovered himself, and courteously asked her pardon for his seeming rudeness.

"Forgive me, fair lady," said he; "it seemed that I saw a ghost in your sweet face."

Adeline, who had recognized him from the descriptions she had received, now made herself known to him, and graciously granted him permission to walk with her to the castle. His offence was readily pardoned when he declared that the cause of it was a fancied resemblance

between Adeline and a dear sister whom death had lately robbed him of. Ere they parted the young people were already deeply in love with one another, and had promised to meet again on the following day. The spot where they had first encountered each other became a trysting-place which was daily hallowed by fresh vows and declarations. On one such occasion Otto told his beloved the story of his early life and revealed to her his identity. It was indeed a harrowing tale, and one which drew a full meed of sympathy from the maiden.

Otto and his sister--she whose likeness in Adeline's face had first arrested his attention--had been brought up by a cruel stepfather, who had treated them so brutally that Otto was at length forced to flee to the castle of an uncle, who received him kindly and gave him an education befitting his knightly station. A few years later he had returned home, to find his sister dead--slain by the ill-treatment of her stepfather, who, it was even said, had hastened her death with poison. Otto, overcome with grief, confronted her murderer, heaped abuse on his head, and demanded his share of the property. The only answer was a sneer, and the youth, maddened with grief and indignation, drew his sword and plunged it in his tormentor's heart. A moment later he saw the probable consequences of his hasty action, concealed himself in the woods, and thenceforth became a fugitive, renounced even by his own uncle, and obliged to remain in hiding in order to escape certain death at the hands of the murdered man's kindred. In a fortunate moment he had chanced to reach Flörsheim, where, in his shepherd's guise, he judged himself secure.

Adeline, deeply moved by the tale, sought to put her sympathy in the practical form of advice.

"Dear Otto," she said, "let us go to my father and tell him all. We must dispatch an embassy to your uncle in Thuringen, to see whether he may not consent to a division of the property. Take courage, and your rightful position may yet be assured."

So it was arranged that on the following day the lovers should seek Sir Bodo and ask his advice in the matter. But alas! ere their plans could be carried out Bodo himself sent for his daughter and informed her that he had chosen a husband for her, Sir Siegebert, a wealthy and noble knight, just returned from Palestine.