THERE was among the sages a writer, Artephius, whose productions are very famous among the Hermetic Philosophers, insomuch that the noble Olaus Borrichius, an excellent writer and a most candid critic, recommends these books to the attentive perusal of those who would acquire knowledge of this sublime highest philosophy. He is said to have invented a cabalistic magnet which possessed the extraordinary property of secretly attracting the aura, or mysterious spirit of human efflorescence and prosperous bodily growth, out of young men; and these benign and healthful springs of life he gathered up, and applied by his magic art to himself--by inspiration, transudation, or otherwise--so that he concentred in his own body, waning in age, the accumulated rejuvenescence of many young people: the individual owners of which new fresh life suffered and were consumed in proportion to the extent in which he preyed vitally upon them, and some of them were exhausted by this enchanter and died. This was because their fresh young vitality had been unconsciously drawn out of them in his baneful, devouring society, which was unsuspected because it afforded a glamour delightful. Now this seems absurd; but it is not so absurd as we suppose when considered sympathetically.

Sacred history affords considerable authority to this kind of opinion. We all are acquainted with the

history of King David, to whom, when he grew old and stricken in years, Abishag, the Shunammite, was brought to recover him--a damsel described as 'very fair'; and we are told that she 'lay in his bosom', and that thereby he 'gat heat'--which means vital heat, but that the king 'knew her not'. This latter clause in 1 Kings i. 4, all the larger critics, including those who speak in the commentaries of Munster, Grotius, Vossius, and others, interpret in the same way. The seraglios of the Mohammedans have more of this less lustful meaning, probably, than is commonly supposed. The ancient physicians appear to have been thoroughly -acquainted with the advantages of the companionship, without irregular indulgence, of the young to the old in the renewal of their vital powers.

The elixir of life was also prepared by other and less criminal means than those singular ones hinted above. It was produced out of the secret chemical laboratories of Nature by some adepts. The famous chemist, Robert Boyle, mentions a preparation in his works, of which Dr. Le Fevre gave him an account in the presence of a famous physician and of another learned man. An intimate friend of the physician, as Boyle relates, had given, out of curiosity, a small quantity of this medicated wine or preparation to an old female domestic; and this, being agreeable to the taste, had been partaken of for ten or twelve days by the woman, who was near seventy years of age, but whom the doctor did not inform what the liquor was, nor what advantage he was expecting that it might effect. A great change did indeed occur with this old woman; for she acquired much greater activity, a sort of youthful bloom came to her countenance, her face was becoming much more smooth and agreeable; and beyond this, as a still more decided step

backward to her youthful period, certain purgationes came upon her again with sufficiently severe indications to frighten her very much as to their meaning; so that the doctor, greatly surprised at his success, was compelled to forego his further experiments, and to suppress all mention of this miraculous new cordial, for fear of alarming people with incomprehensible novelties--in regard to which they are very tenacious, having prejudices inveterate.

But with respect to centenarians, some persons have been mentioned as having survived for hundreds of years, moving as occasion demanded from country to country; when the time arrived that, in the natural course of things, they should die, or be expected to die, merely changing their names, and reappearing in another place as new persons--they having long survived all who knew them, and thus being safe from the risk of discovery. The. Rosicrucians always most jealously guarded these secrets, speaking in enigmas and parables for the most part; and they adopted as their motto the advice of one of their number, one of the Gnostics of the early Christian period: 'Learn to know all, but keep thyself unknown'. Further, it is not generally known that the true Rosicrucians bound themselves to obligations of comparative poverty but absolute chastity in the world, with certain dispensations and remissions that fully answered their purpose; for .they were not necessarily solitary people: on the contrary, they were frequently gregarious, and mixed freely with all classes, though privately admitting no law but their own.

Their notions of poverty, or comparative poverty, were different from those that usually prevail. They felt that neither monarchs nor the wealth of monarchs could endow or aggrandize those who already esteemed

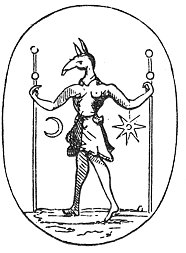

themselves the superiors of all men; and therefore, though declining riches, they were voluntary in the renunciation of them. They held to chastity, because, entertaining some very peculiar notions about the real position in creation of the female sex, the Enlightened or Illuminated Brothers held the monastic or celibate state to be infinitely that more consonant with the intentions of Providence, since in everything possible to man’s frail nature they sought to trample on the pollutions and the great degradation of this his state in flesh. They trusted the great lines of Nature, not in the whole, but in part, as they believed Nature was in certain senses not true and a betrayer, and that she was not wholly the benevolent power to endow, as accorded with the prevailing deceived notion. We wish not to discuss more particularly than thus the extremely refined and abstruse protesting views of these fantastic religionists, who ignored Nature. We have drawn to ourselves a certain frontier of reticence, up to which margin we may freely comment; and the limit is quite extended enough for the present popular purpose, though we absolutely refuse to overpass it with too distinct explanation, or to enlarge further on the strange persuasions of the Rosicrucians.

There is related, upon excellent authority, to have happened an extraordinary incident at Venice, that made a very great stir among the talkers in that ancient place, and which we will here supply at length, as due to so mysterious and amusing an episode. Every one who has visited Venice in these days, and still more those of the old-fashioned time who have put their experience of it on record, are aware that freedom and ease among persons who make a good appearance prevail there to an extent that; in this reserved and suspicious country, is difficult to realize.

[paragraph continues] This doubt of respectability until conviction disarms has a certain constrained and unamiable effect on our English manners, though it occasionally secures us from imposition, at the expense perhaps of our accessibility. A stranger who arrived in Venice one summer, towards the end of the seventeenth century, and who took up his residence in one of the best sections of the city, by the considerable figure which, he made, and through his own manners, which were polished, composed, and elegant, was admitted into the best company--this though he came with no introductions, nor did anybody exactly know who or what he was. His figure was exceedingly elegant and well-proportioned, his face oval and long, his forehead ample and pale, and the intellectual faculties were surprisingly brought out, and in distinguished prominence. His hair was long, dark, and flowing; his smile inexpressibly fascinating, yet sad; and the deep light of his eyes seemed laden, to the attention sometimes of those noting him, with the sentiments and experience of all the historic periods. But his conversation, when he chose to converse, and his, attainments and knowledge, were marvellous; though he seemed always striving to keep himself back, and to avoid saying too much, yet not with an ostentatious reticence. He went by the name of Signor Gualdi and was looked upon as a plain private gentleman, of moderate independent estate. He was an interesting character; in short, one to make an observer speculate concerning him.

This gentleman remained at Venice for some. months, and was known by the name of 'The Sober Signior' among the common people, on account of the regularity of his life, the composed simplicity of, his manners, and the quietness of his costume; for he always wore dark clothes, and these of a plain, unpretending

style. Three things were remarked of him during his stay at Venice. The first was, that he had a small collection of fine pictures, which he readily showed to everybody that desired it; the next, that he seemed perfectly versed in all arts and sciences, and spoke always with such minute correctness as to particulars as astonished, nay, silenced, all who heard him, because he seemed to have been present at the occurrences which he related, making the most unexpected correction in small facts sometimes. And it was, in the third place, observed that he never wrote or received any letter, never desired any credit, but always paid for everything in ready money, and made no use of bankers, bills of exchange, or letters of credit. However, he always seemed to have enough, and he lived respectably, though with no attempt at splendour or show.

Signor Gualdi met, shortly after his arrival at Venice, one day, at the coffee-house which he was in the habit of frequenting, a Venetian nobleman of sociable manners, who was very fond of art, and this pair used to engage in sundry discussions; and they had many conversations concerning the various objects and pursuits which were interesting to both of them. Acquaintance ripened into friendly esteem; and the nobleman invited Signor Gualdi to his private house, whereat--for he was a widower--Signor Gualdi first met the nobleman's daughter, a very beautiful young maiden of eighteen, of much grace and intelligence, and of great accomplishments. The nobleman's daughter was just introduced at her father's house from a convent, or pension, where she had been educated by the nuns. This young lady, in short, from constantly being in his society, and listening to his interesting narratives, gradually fell in love with the mysterious stranger, much for the reasons of

[paragraph continues] Desdemona; though Signor Gualdi was no swarthy Moor, but only a well-educated gentleman--a thinker rather than the desirer to be a doer. At times, indeed, his countenance seemed to grow splendid and magical in expression; and he boasted certainly wondrous discourse; and a strange and weird fascination would grow up about him, as it were, when he became more than usually pleased, communicative, and animated. Altogether, when you were set thinking about him, he seemed a puzzling person, and of rare gifts; though when mixing only with the crowd you would scarcely distinguish him from the crowd; nor would you observe him, unless there was something romantically .akin to him in you excited by his talk.

And now for a few remarks on the imputed character of these Rosicrucians. And in regard to them, however their existence is disbelieved, the matters of fact we meet with, sprinkled, but very sparingly, in the history of these hermetic people, are so astonishing, and at the same time are preferred with such confidence, that if we disbelieve--which it is impossible to avoid, and that from the preposterous and unearthly nature of their pretensions--we cannot escape the conviction that, if there is not foundation for it, their impudence and egotism is most audacious. They speak of all mankind as infinitely beneath them; their pride is beyond idea, although they are most humble and quiet in exterior. They glory in poverty, and declare that it is the state ordered for them; and this though they boast universal riches. They decline all human affections, or submit to them as advisable escapes only--appearance of loving obligations, which are assumed for convenient acceptance, or for passing in a world which is composed of them, or of their supposal. They mingle most gracefully in the society of women, with hearts wholly incapable

of softness in this direction; while they criticize them with pity or contempt in their own minds as altogether another order of beings from men, They are most simple and deferential in their exterior; and yet the self-value which fills their hearts ceases its self-glorying expansion only with the boundless skies. Up to a certain point, they are the sincerest people in the world; but rock is soft to their impenetrability afterwards. In comparison with the hermetic adepts, monarchs are poor, and their greatest accumulations are contemptible. By the side of the sages, the most learned are mere dolts and blockheads. They make no movement towards fame, because they abnegate and disdain it. If they become famous, it is in spite of themselves: they seek no honours, because there can be no gratification in honours to such people. Their greatest wish is to steal unnoticed and unchallenged through the world, and to amuse themselves with the world because they are in it, and because they find it about them. Thus, towards mankind they are negative; towards everything else, positive; self-contained, self-illuminated, self-everything; but always prepared (nay, enjoined) to do good, wherever possible or safe.

To this immeasurable exaltation of themselves, what standard of measure, or what appreciation, can you apply? Ordinary estimates fail in the idea of it. Either the state of these occult philosophers is the height of sublimity, or it is the height of absurdity. Not being competent to understand them or their claims, the world insists that these are futile. The result entirely depends upon their being fact or fancy in the ideas of the hermetic philosophers. The puzzling part of the investigation is, that the treatises of these profound writers abound in the most acute discourse upon difficult subjects, and contain splendid

passages and truths upon all subjects--upon the nature of metals, upon medical science, upon the unsupposed properties of simples, upon theological and ontological speculation, and upon science and objects of thought generally--upon all these matters they enlarge to the reader stupendously--when the proper attention is directed to them.