The Philistines, by R.A.S. Macalister, [1913], at sacred-texts.com

THE PHILISTINES

THEIR HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION

CHAPTER I

THE ORIGIN OF THE PHILISTINES

The Old Testament history is almost exclusively occupied with Semitic tribes. Babylonians, Assyrians, Canaanites, Hebrews, Aramaeans—all these, however much they might war among themselves, were bound by close linguistic and other ties, bespeaking a common origin in the dim, remote recesses of the past. Even the Egyptians show evident signs of having been at least crossed with a Semitic strain at some period early in their long and wonderful history. One people alone, among those brought conspicuously to our notice in the Hebrew Scriptures, impresses the reader as offering indications of alien origin. This is the people whom we call 'Philistines'.

If we had any clear idea of what the word 'Philistine' meant, or to what language it originally belonged, it might throw such definite light upon the beginnings of the Philistine people that further investigation would be unnecessary. The answer to this question is, however, a mere matter of guess-work. In the Old Testament the word is regularly written Pelištīm (פְּלִשְׁתִּים), singular Pelištī (פְּלִשְׁתִּי), twice 1 Pelištīyim (פְּלִשְׁתִּיִים), The territory which they inhabited during the time of their struggles with the Hebrews is known as ’ereṣ Pelištim (אֶרֶץ פְּלִשְׁתִּים) 'the Land of Philistines', or in poetical passages, simply Pelešeth (פֶּלֶשֶׁת) 'Philistia'. Josephus regularly calls them Παλαιστινοί, except once, in his version of the Table of Nations in Genesis x (Ant. I. vi. 2) where we have the genitive singular Φυλιστίνου.

Various conjectures as to the etymology of this name have been put forward from time to time. One of the oldest, that apparently due to Fourmont, 1 connects it with the traditional Greek name Πελασγοί; an equation which, however, does no more than move the problem of origin one step further back. This theory was adopted by Hitzig, the author of the first book in modern times on the Philistines, 2 Who connected the word with Sanskrit valakṣa 'white', and made other similar comparisons, as for instance between the name of the deity of Gaza, Marna, and the Indian Varuna. On the other hand a Semitic etymology was sought by Gesenius, 3 Movers, 4 and others, who quoted an Ethiopic verb falasa, 'to wander, roam,' whence comes the substantive fallási, 'a stranger.' In this etymology they were anticipated by the translators of the Greek Version, who habitually render the name of the Philistines by the Greek word ἀλλόφυλοι, 5 even when it is put into the mouths of Goliath or Achish, when speaking of themselves. Of course this is merely an etymological speculation op the part of the translators, and proves nothing more than the existence of a Hebrew root (otherwise apparently unattested) similar in form and meaning to the Ethiopic root cited. And quite apart from any questions of linguistic probability, there is an obvious logical objection to such an etymology. In the course of the following pages we shall find the court scribes of Ramessu III, the historians of Israel, and the keepers of the records of the kings of Assyria, agreeing in applying the same name to the nation in question. These three groups of writers, belonging to as many separate nations and epochs of time, no doubt worked independently of each other—most probably in ignorance of each other's productions. This being so, it follows almost conclusively that the name 'Philistine' must have been derived from Philistine sources, and in short must have been the native designation. Now a word meaning 'stranger' or the like, while it might well be applied by foreigners to a nation deemed by them

intruders, would scarcely be adopted by the nation itself, as its chosen ethnic appellation. This Ethiopic comparison it seems therefore safe to reject. The fantasy that Redslob 1 puts forward, namely, that פלשׁת 'Philistia' was an anagram for שׁפלה, the Shephelah or foot-hills of Judea, is perhaps best forgotten: place-names do not as a rule come to be in this mechanical way, and in any case 'the Shephelah' and 'Philistia' were not geographically identical.

There is a peculiarity in the designation of the Philistines in Hebrew which has often been noticed, and which must have a certain significance. In referring to a tribe or nation the Hebrew writers as a rule either (a) personified an imaginary founder, making his name stand for the tribe supposed to derive from him—e. g. 'Israel' for the Israelites; or (b) used the tribal name in the singular, with the definite article—a usage sometimes transferred to the Authorized Version, as in such familiar phrases as 'the Canaanite was then in the land' (Gen. xii. 6); but more commonly assimilated to the English idiom which requires a plural, as in 'the iniquity of the Amorite[s] is not yet full' (Gen. xv. 16). But in referring to the Philistines, the plural of the ethnic name is always used, and as a rule the definite article is omitted. A good example is afforded by the name of the Philistine territory above mentioned, ’ereṣ Pelištīm, literally 'the land of Philistines': contrast such an expression as ’ereṣ hak-Kena‘anī, literally 'the land of the Canaanite'. A few other names, such as that of the Rephaim, are similarly constructed: and so far as the scanty monuments of Classical Hebrew permit us to judge, it may be said generally that the same usage seems to be followed when there is question of a people not conforming to the model of Semitic (or perhaps we should rather say Aramaean) tribal organization. The Canaanites, Amorites, Jebusites, and the rest, are so closely bound together by the theory of blood-kinship which even yet prevails in the Arabian deserts, that each may logically be spoken of as an individual human unit. No such polity was recognized among the pre-Semitic Rephaim, or the intruding Philistines, so that they had to be referred to as an aggregate of human units. This rule, it must be admitted, does not seem to be rigidly maintained; for instance, the name of the pre-Semitic Horites might have been expected to follow the exceptional construction. But a hard-and-fast adhesion to so subtle a distinction, by all the writers who have contributed to the canon of the Hebrew scriptures and by

all the scribes who have transmitted their works, is not to be expected. Even in the case of the Philistines the rule that the definite article should be omitted is broken in eleven places. 1

However, this distinction, which in the case of the Philistines is carefully observed (with the exceptions cited in the footnote), indicates at the outset that the Philistines were regarded as something apart from the ordinary Semitic tribes with whom the Hebrews had to do.

The name of the Philistines, therefore, does not lead us very far in our examination of the origin of this people. Our next step must be to inquire what traditions the Hebrews preserved respecting the origin of their hereditary enemies; though such evidence on a question of historical truth must obviously even under the most favourable circumstances be unsatisfactory.

The locus classicus is, of course, the table of nations in Genesis x. Here we read (vv. 6, 13, 14), 'And the sons of Ham: Cush, and Mizraim, and Put, and Canaan. . . And Mizraim begat Ludim, and ‘Anamim, and Lehabim, and Naphtuhim, and Pathrusim, and Casluhim (whence went forth the Philistines) and Caphtorim.' The list of the sons of Ham is assigned to the Priestly source; that of the sons of Mizraim (distinguished by the formula 'he begat') to the Yahvistic source. The ethnical names are almost all problematical, and the part of special interest to us has been affected, it is supposed, by a disturbance of the text.

So far as the names can be identified at all, the passage means that in the view of the writer or writers who compiled the table of nations, the Hamitic or southern group of mankind were Ethiopia, Egypt, 'Put', and Canaan. Into the disputed question of the identification of the third of these, this is not the place to enter. Passing over the children assigned to Cush or Ethiopia, we come to the list of peoples supposed by the Yahvist to be derived from Egypt. Who or what most of these peoples were is very uncertain. The Ludim are supposed to have been Libyans (d in the name being looked upon as an error for b); the Lehabim are also supposed to be Libyans; the ‘Anamim are unknown, as are also the Casluhim; but the Naphtuhim and Pathrusim seem to be reasonably identified with the inhabitants of Lower and Upper Egypt respectively. 2

There remain the Caphtorim, and the interjected note 'whence went forth the Philistines'. The latter has every appearance of having originally been a marginal gloss that has crept into the text. And in the light of other passages, presently to be cited, it would appear that the gloss referred originally not to the unknown Casluhim, but to the Caphtorim. It must, however, be said that all the versions, as well as the first chapter of Chronicles, agree in the reading of the received text, though emendation would seem obviously called for. This shows us either that the disturbance of the text is of great antiquity, or else that the received text is, after all, correct, and that the Casluhim are to be considered a branch of, or at any rate a tribe nearly related to, the Caphtorim.

The connexion of the Philistines with a place called Caphtor is definitely stated in Amos ix. 7: 'Have not I brought up Israel out of the land of Egypt, and the Philistines from Caphtor, and the Syrians from Kir?' It is repeated in Jeremiah xlvii. 4, where the Philistines are referred to as 'the remnant of the ’i of Caphtor'. The word ’i is rendered in the Revised Version 'island', with marginal rendering 'sea coast': this alternative well expresses the ambiguity in the meaning of the word, which does not permit us to assume that Caphtor, as indicated by Jeremiah, was necessarily one of the islands of the sea. Indeed, even if the word definitely meant 'island', its use here would not be altogether conclusive on this point: an isolated headland might long pass for an island among primitive navigators, and therefore such a casual mention need not limit our search for Caphtor to an actual island.

Again, in Deuteronomy ii. 23, certain people called the Caphtorim, 'which came out of Caphtor', are mentioned as having destroyed the ‘Avvim that dwelt in villages as far as Gaza, and established themselves in their stead. The geographical indication shows that the Caphtorim must be identified, generally speaking, with the Philistines: the passage is valuable as a record of the name of the earlier inhabitants, who, however, were not utterly destroyed: they remained in the south of the Philistine territory (Joshua xiii. 4).

The question of the identification of Caphtor must, however, be postponed till we have noted the other ethnic indications which the Hebrew scriptures preserve. Chief of these is the application of the word Cerēthi (כְּרֵתִי) 'Cherēthites' to this people or to a branch of them.

Thus in 1 Samuel xxx. 14 the young Egyptian servant, describing the Amalekite raid, said 'we raided the south of the Cherethites and

the property of Judah and the south of the Calebites and burnt Ziklag with fire'. In Ezekiel xxv. 16 the Philistines and the Cherethites with the 'remnant of the sea-coast' are closely bound together in a common denunciation, which we find practically repeated in the important passage Zephaniah ii. 5, where a woe is pronounced on the dwellers by the sea-coast, the nation of the Cherethites, and on 'Canaan, the land of the Philistines'; this latter is a noteworthy expression, probably, however, interpolated in the text. In both these last passages the Greek version renders this word Κρῆτες 'Cretans '; elsewhere it simply transliterates (Χελεθί, with many varieties of spelling). 1

In both places it would appear that the name 'Cherethites' is chosen for the sake of a paronomasia (כרת = 'to cut off'). In the obscure expression 'children of the land of the covenant' (בני אדץ הברית Ezek. xxx. 5) some commentators 2 see a corruption of בני הכרתי 'Children of the Cherethites'. But see the note, p. 123 post.

In other places the Cherethites are alluded to as part of the bodyguard of the early Hebrew kings, and are coupled invariably with the name פְּלֵתִי Pelēthites. This is probably merely a modification of פלשתי, the ordinary word for 'Philistine', the letter s being omitted in order to produce an assonance between the two names. 3 The Semites are fond of such assonances: they are not infrequent in modern Arab speech, and such a combination as Shuppīm and Ḫuppīm (1 Chron. vii. 12) shows that they are to be looked for in older Semitic writings as well. If this old explanation 4 be not accepted, we should have to put the word 'Pelethites' aside as hopelessly unintelligible. Herodotus's Philitis, or Philition, a shepherd after whom the Egyptians were alleged to call the Pyramids, 5 has often been quoted in connexion with this name, coupled with baseless speculations as to whether the Philistines could have been the Hyksos.

With regard to the syntax of these two names, it is to be noticed that as a rule they conform to the ordinary Hebrew usage, contrary perhaps to what we might have expected. But in the two prophetic passages we have quoted, the name of the Cherethites agrees in construction with that of the Philistines.

In three passages—2 Samuel xx. 23, 2 Kings xi. 4, 19—the name of the royal body-guard of 'Cherethites' appears as כָּרִי 'Carians'. If this happened only once it might be purely accidental, due to the dropping of a ת by a copyist; but being confirmed by its threefold repetition, it is a fact that must be noted carefully 1 for future reference.

Here the Hebrew records leave us, and we must seek elsewhere for further light. Thanks to the discoveries of recent years, our search need not be prolonged. For in the Egyptian records we find mention of a region whose name, Keftiu, has an arresting similarity to the 'Caphtor' of Hebrew writers. It is not immediately obvious whence comes the final r of the latter, if the comparison be sound; but waiving this question for a moment, let us see what is to be made of the Egyptian name, and, above all, what indications as to its precise situation are to be gleaned from the Egyptian monuments.

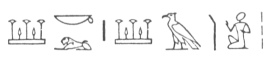

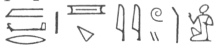

The name k-f-tïw (

) sometimes written k-f-ty-w (

) sometimes written k-f-ty-w (

) first meets us on Egyptian monuments of the Eighteenth Dynasty. It is apparently an Egyptian word: at least, it is capable of being rendered behind', and assuming this rendering Mr. H. R. Hall 2 aptly compares it with our colloquialism 'the Back of Beyond'. Unless this is to be put aside as a mere Volksetymologie, it clearly would be useless to search the maps of classical atlases for any name resembling Keftiu. It would simply indicate that the Egyptians had a sense of remoteness or uncertainty about the position of the country; and even from this we could derive no help, for as a rule they manifest a similar vagueness about other foreign places.

) first meets us on Egyptian monuments of the Eighteenth Dynasty. It is apparently an Egyptian word: at least, it is capable of being rendered behind', and assuming this rendering Mr. H. R. Hall 2 aptly compares it with our colloquialism 'the Back of Beyond'. Unless this is to be put aside as a mere Volksetymologie, it clearly would be useless to search the maps of classical atlases for any name resembling Keftiu. It would simply indicate that the Egyptians had a sense of remoteness or uncertainty about the position of the country; and even from this we could derive no help, for as a rule they manifest a similar vagueness about other foreign places.

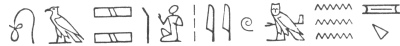

It is specifically under Thutmose III that 'Keftiu' first appears as the name of a place or a people. On the great stele in the Cairo Museum in which the king's mighty deeds are summarized, in the form of a Hymn to Amon, we read 'I came and caused thee to smite the west-land, and the land of Keftiu and Asi (

)

)

are terrified'. In the Annalistic Inscription on the walls of the Temple of Karnak the name appears in interesting connexion with maritime enterprise. 'The harbours of the king were supplied with all the good things which he received in Syria, namely ships of Keftiu, Byblos, and Sektu [the last-named place is not identified], cedar-ships laden with poles and masts.' 'A silver vessel of Keftiu work' was part of the tribute paid to Thutmose by a certain chieftain. 1 Keftiu itself does not send any tribute recorded in the annals; but tribute from the associated land of Asi is enumerated, in which copper is the most conspicuous item. This in itself proves nothing, for the copper might in the first instance have been brought to Asi from somewhere else, before it passed into the coffers of the all-devouring Pharaoh: but on the Tell el-Amarna tablets a copper-producing country, with the similar name Alašia, is prominent, and as Cyprus was the chief if not the only source of copper in the Eastern Mediterranean, the balance of probability seems to be in favour of equating Asi and Alašia alike to Cyprus. In this case Keftiu would denote some place, generally speaking, in the neighbourhood of Cyprus.

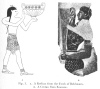

The next important sources of information are the wall-paintings in the famous tombs of Sen-mut, architect to Queen Hatshepsut; of Rekhmara, vizier of Thutmose III; and of Menkheperuseneb, son of the last-named official, 2 high priest of Amon and royal treasurer. In these wall-paintings we see processions of persons, with non-Semitic European-looking faces; attired simply in highly embroidered loincloths folded round their singularly slender waists, and in high boots or gaiters; with hair dressed in a distinctly non-Semitic manner; bearing vessels and other objects of certain definite types. The tomb of Sen-mut is much injured, but the Cretan ornaments there drawn are unmistakable. In the tomb of Rekhmara we see the official standing, with five rows of foreigners carrying their gifts, a scribe recording the inventory at the head of each row, and an inscription explaining the scene as the 'Reception by the hereditary prince Rekhmara of the tribute of the south country, with the

tribute of Punt, the tribute of Retenu, the tribute of Keftiu, besides the booty of all nations brought by the fame of Thutmose III'. In the tomb of Menkheperuseneb there are again two lines of tribute-bearers, described as 'the chief of Keftiu, the chief of Kheta, the chief of Tunip, the chief of Kadesh'; and an inscription asserts that these various chiefs are praising the ruler of the Two Lands, celebrating his victories, and bringing on their backs silver, gold, lapis lazuli, malachite, and all kinds of precious stones.

Click to enlarge

(left) Fig. 1. A. A Keftian from the Tomb of Rekhmara. (right) B. A Cretan from Knossos.

Some minor examples, confirming the conclusions to which these three outstanding tomb-frescoes point, will be found in W. Max Müller's important paper, Neue Darstellungen 'mykenischer' Gesandter . . . in altägyptischen Wandgemälden (Mitt. vorderas.-Gesell., 1904, No. 2).

Recent investigations in the island of Crete have enabled us to identify with certainty the sources of the civilization which these messengers and their gifts represent. Wall-paintings have there been found representing people with the same facial type, the same costume, the same methods of dressing the hair; and as it were the originals of the costly vases they bear have been found in such profusion as to leave no doubt that they are there on their native soil. The messengers, who are depicted in the Egyptian frescoes, are introducing into Egypt

some of the chefs-d’œuvre of Cretan art; specifically, art of the periods known as Late Minoan I and II, 1 the time of the greatest glory of the palace of Knossos; and as they are definitely described in the accompanying hieroglyphs as messengers of Keftiu, it follows that Keftiu was at least a centre of distribution of the products of Cretan civilization, and therefore a place under the influence of Crete, if it was not actually the island of Crete itself. And the clear evidence, that excavation in Crete has revealed, of a back-wash of Egyptian influence on Cretan civilization at the time of the coming to Egypt of the Keftian envoys, turns the probability into as near a certainty as it is at present possible to attain.

The next document to be noticed is a hieratic school exercise-tablet, apparently (to judge from the forms of the script) dating from the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty. It is now preserved in the British Museum, numbered 5647. 2 On the one side are some random scribbles, like the meaningless words and phrases with which one tries a doubtful pen:

On the other side is

Ašaḫurau

Nasuy

Akašou

Adinai

Pinaruta

Rusa

Sen-Nofer [an Egyptian name, twice repeated]

Akašou

"a hundred of copper, aknu-axes" [reading uncertain]

Beneṣasira

[two illegible names]

Sen-nofer

Sumrssu [Egyptian]'

[paragraph continues] Though the reading of some of the items of this list is not quite certain, it seems clear that the heading ’irt rn n keftw, 'to make names of Keftiu', indicates that this tablet is a note of names to be used

in some exercise or essay. The presence of the familiar Philistine name Achish, in the form Akašou, twice over, is suggestive, but otherwise the tablet does not help forward our present inquiry into the position of Keftiu and the origin of the Philistine people.

These various discoveries of recent years make it unnecessary to discuss at any length other theories which have been presented in ancient and modern times as to the identification of the name of Keftiu or of Caphtor. The Ptolemaic Jonathan Oldbuck who translated for his master the Decree of Canopus into Hieroglyphics, revived this ancient geographical name to translate Φοινίκης: a piece of irresponsible pedantry which has caused nothing but confusion. Even before the discoveries of the last fifteen or twenty years it was obvious that the Keftiu of Rekhmara's tomb were as unlike Phoenicians as they could possibly be; and their gifts were also incompatible with what was known of Phoenician civilization. Endless trouble was thus given to would-be harmonists. Another antiquary of the same kind and of the same period, who drew up the inscription to be cut on the temple at Kom Ombo, has likewise made illegitimate use of the name in question. A catalogue of the places conquered by the founder of the temple, after the manner of the records of achievements of the great kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty, was de rigueur: so the obsequious scribe set down, apparently at random, a list of any geographical names that happened to come into his head. Among these is kptar, the final r of which seems to denote a Hebrew source; perhaps he learnt the name from some brother antiquary in the neighbouring Jewish colony at Aswân.

The Greek translators of the scriptures, the Peshitta, and the Targums, in Deuteronomy ii. 23, Amos ix. 7, render the name Cappadocia. This seems to be merely a guess, founded on similarity of sound.

In modern times, even before the days of scientific archaeology, the equation of Caphtor to Crete has always been the theory most in favour. Apart from Jeremiah's description of the place as an 'island'—which as we have already mentioned is not quite conclusive—the obvious equation Cherethites = Cretans would strike any student. Calmet 1 gives a good statement of the arguments for the identification which were available before the age of excavation.

For completeness’ sake we may refer here to various other theories of Philistine origin which have been put forward by modern scholars: it is, however, not necessary to give full references

to all the writers who have considered the question. The favourite hypothesis among those who rejected the Caphtor-Crete identification was founded on the Greek Version and Josephus: Caphtor was by them identified with Cappadocia, and Casluhim with the Colchians. Hitzig, as stated earlier in this chapter, identified them with the Pelasgians, who came, according to his view, from Crete to North Egypt, identified with the Casluhim of the Table of Nations: their language he supposed to be cognate with Sanskrit, and by Sanskrit he interpreted many of the names of people and places. Quatremère, reviewing Hitzig's book in the Journal des Savants (1846, pp. 257, 411), suggested a rival theory, deriving them from West Africa, equating Casluhim with Sheluḫ, a sept of the Berbers. Stark (Gaza, p. 70) assigned them to the Phoenicians, accepting the South Semitic etymology of the name Pelištim, Caphtor being the Delta, and Casluhim a name cognate with the Kasios mountain, denoting a tribe living between Kasios and Pelusium. 1 Köhler 2 had a complicated theory to reconcile all the various lines of Biblical evidence: he took Caphtor to be the Delta; the Philistines springing from there settled in Casluhim (between Casios and Pelusium): 'going forth' from Casluhim they sailed to Crete, and then returned to Philistia. Knobel (Die Völkertafel der Genesis, p. 215 sqq.) proposed a double origin for the Philistine people. The main body he took to be Semites who came out (geographically, not racially) from the Casluhim in North Egypt; and the Caphtorim were a southern tribe of Cretan or Carian origin. Knobel gave a very careful analysis of the evidence available at his time, but he overlooked the Medinet Habu sculptures, and, on the other hand, gave too much weight to the gossip of Herodotus about Philitis and the Pyramids.

Ebers 3 made an elaborate attempt to find in the Delta a site for Caphtor; but this can hardly stand against later discoveries. They are no goods from the Land of Goshen which Rekhmara's visitors are carrying. W. Max Müller 4 equates Keftiu to Cilicia, mainly on the ground of the order in which the name occurs in geographical lists: but though this is not an argument to be lightly set aside, we are confronted with the difficulty that Cilicia could hardly have been a centre of distribution of Minoan goods in the time of Rekhmara. 5

Schwally 1 argues thus for the Semitic origin of the Philistines: that if the Philistines were immigrants, so were the Phoenicians and Syrians (teste Amos): that the identity of Caphtor and Crete is an unproved assumption: the Greek translation twice renders 'Cherethites' by 'Cretans', it is true, but not elsewhere, showing uncertainty on the subject: and the reading 'Crete' in Zephaniah ii. 6 is wrong. All the personal names, and all the place-names (except possibly El-tekeh and Ziklag) are Semitic, and there is no trace of any non-Semitic deity. Stade 2 asserts the Semitic origin of the people, without giving any very definite proofs; Tiele 3 claims the Philistines as Semites on the ground of their Semitic worship. Beecher (in Hastings's Dict. of the Bible, s. v. Philistines) claims the name of the people as 'probably Semitic', but considers that most likely they were originally Aryan pirates who had become completely Semitized. The non-circumcision of the Philistines is a difficulty against assigning to them a Semitic origin; and the various Semitic elements in their names, religion, and language can most reasonably be explained by borrowing—presumably as a result of free intermarriage with Semites or Semitized aborigines.

On the other hand, it may be said at once that it is perhaps a little premature to call them Aryans. On the whole, the probability seems to be against the Philistine being an Aryan tongue—it certainly was not, if (as is not unlikely) it had affinities with Etruscan.

But these identifications are to a large extent the personal opinions of those who put them forward. The identification of Caphtor and Keftiu with Crete is so generally accepted, that there is a danger that some difficulties in the way should be overlooked. For first of all we are met with a question of philology: whence came the final r in the Hebrew word? It has been suggested that it might be a nominative suffix of the Keftian language. It would in any case be more probably a locative or prepositional suffix: for place-names are apt to get taken over into foreign languages in one or other of those cases, because they are generally referred to in contexts that require them; just as Ériu, the old Irish name of Ireland, has been taken over into English in its prepositional case, now spelt Erin. It might possibly be a plural: Mr. Alton has suggested to me a comparison with the Etruscan plural ending er, ar, ur. Letting the question of the exact case pass, however, as irrelevant, there are two points that must be indicated regarding the suggestion that r is

a Keftian case-ending. In the first place, it assumes that Keftiu is, after all, not the Egyptian word it resembles, but the native 'Keftian' name for the place in question: it is incompatible with the 'Back of Beyond' theory of the meaning of the name. In the second place, it is difficult to understand how the Hebrews should have picked up a 'Keftian' case-ending or any such grammatical formative, rather than the Egyptians; for the Egyptians were brought into direct contact with Keftians, while the Hebrews arrived on the scene too late to enjoy that advantage. Ebers attempted to solve the difficulty by supposing the r to come from the Egyptian adjective wr, 'great', tacked on to the place-name. Max Muller (Asien und Europa, p. 390) and Wiedemann (Orient. Litteraturzeitung, xiii, col. 49) point out that there is no monumental evidence for such an expression, and that in any case 'Great Keftland' would be Keft-‘ā, not Keft-wr. The latter (loc. cit.) has an ingenious solution: in an astronomical text in the grave of Ramessu VI occurs a list of places ‘iwmȝr (the land of the Amorites) pb (unidentified) and

kftḥr ('Upper Kefti'). 'Caphtor', he suggests, may be a corruption of this latter expression. The hypothesis may be noted in passing, though perhaps it is not altogether convincing.

kftḥr ('Upper Kefti'). 'Caphtor', he suggests, may be a corruption of this latter expression. The hypothesis may be noted in passing, though perhaps it is not altogether convincing.

Behind this problem lies another, perhaps equally difficult: why did the Hebrews call the home-land of the Philistines by this name, which even in Egypt was already obsolete?

To this question the only reasonable answer that seems to present itself is to the effect that by the time of the Hebrews Crete or Keftiu had, with its gorgeous palaces, passed into tradition. Like the I Breasail or Avallon of Celtic tradition, the place which the Hebrew writers called 'Caphtor' was no longer a tangible country, but a dreamland of folklore, the legends of which had probably filtered into Palestine from Egypt itself. Whether Caphtor was or was not the same as the island of Crete was to the ancient Hebrew historian a question of secondary interest beside the all-important practical fact that the Philistines were obstinate in their occupation of the most desirable parts of the Promised Land. When the inspired herdsman of Tekoa spoke of the Philistines being led from Caphtor, he was probably just as unconscious of the requirements of the scientific historian as a modern herdsman who told me that a certain ancient monument on a Palestinian hill-slope belonged 'to the time of the Rūm'. He no doubt believed what he said: but who or what the Rūm may have been, or how many years or centuries

or geological aeons ago they may have flourished, he neither knew nor cared.

All, then, that the Hebrews can tell us about their hereditary enemies is, that they came from a vague traditional place called Caphtor—a place by the sea, but of which they have nothing more to say. The tradition of Caphtor seems to be a tradition of the historical glories of Crete, so far as the Egyptians knew of them, and the name seems to be a tradition of the name which, for some reason not certainly known, the Egyptians applied to the source of the desirable treasures of the Cretan civilization.

Even down to late times the tradition linking Philistia with Crete persisted in one form or another. Tacitus heard it, though in a distorted form: in the oft-quoted passage Hist. v. 2 he confuses the Jews with the Philistines, and makes the former the Cretan refugees. 1 ΜΕΙΝΩ, Minos, is named on some of the coins of Gaza. This town was called by the name Minoa: and its god Marna was equated to 'Zeus the Crete-born.' 2

But did the Philistines come from Crete? That is the question which we must now consider.

The last generation saw the labours of Schliemann at Troy and elsewhere, and was startled by the discovery of the splendid pre-Hellenic civilization of Mycenae. For us has been reserved the yet greater surprise of finding that this Mycenaean age was but the latest, indeed the degenerate phase of a vastly older and higher culture. Of this ancient civilization Crete was the centre and the apex.

The course of civilization in this island, from the end of the Neolithic period onwards, is divided by Sir Arthur Evans into three periods 3 which he has named Early, Middle, and Late 'Minoan' respectively, after the name of Minos the famous legendary Cretan king. Each of these three periods is further divided into subordinate

periods, indicated by numbers; thus we have Early Minoan I, II, III, and so for the others. The general characters of these nine periods may now be briefly stated, with the approximate dates which Egyptian synchronisms enable us to assign.

Into the question of the origin of the early inhabitants of Crete we need not enter. That there was some connexion between Crete and Egypt in their stone-age beginnings seems on various grounds to be not improbable. 1 The neolithic Cretan artists were much like neolithic artists elsewhere. They never succeeded in attaining a very high position among workers in flint; Crete has so far produced nothing comparable with the best work of the Egyptians and the Scandinavians. Their pottery was decorated with incised or pricked patterns filled in with white powdered gypsum, to make a white pattern on a black ground.

The Early Minoan I period inherited this type of ornament and ware from its predecessors, but improved it. Coloured decoration now began to be used, the old incised ornaments being imitated with a wash of paint. The ornament was restricted to simple geometrical patterns such as zigzags. The pottery was made without the wheel. In this period short triangular daggers in copper are found. In Early Minoan II the designs are more free and graceful: simple curves appear, side by side with straight lines, towards the end of the period. The potter's wheel is introduced. Rude and primitive idols in marble, alabaster, and steatite are found. The copper daggers are likewise found, but the use of flint and obsidian is not yet wholly abandoned. In Early Minoan III there is not much advance in the art of the potter. We now, however, begin to find seals with a kind of hieroglyphic signs upon them, apparently imitated (in manner if not in matter) from Egyptian seals. These seem to give us the germ of the art of writing, as practised later in Crete. Scholars differ (between 2000 and 3000 B.C.) as to the proper date to assign to the end of the Early Minoan civilization: for our present purpose it is not important to discuss the causes of disagreement, or to attempt to decide between these conflicting theories.

The next period, Middle Minoan I, takes a great step forward. We now begin to find polychrome decoration in pottery, with elaborate geometrical patterns; we also discover interesting attempts to picture natural forms, such as goats, beetles, &c. Upon the ruins of this stage of development, which seems to have been checked by some catastrophe, are founded the glories of Middle Minoan II, the period of the great palace of Phaestos and of the first palace of

[paragraph continues] Knossos. To this period also belongs the magnificent polychrome pottery called Kamáres ware. Another catastrophe took place: the first palace of Knossos was ruined, and the great second palace built in its place: and the period known as Middle Minoan III began. It was distinguished by an intense realism in art, speaking clearly of a rapid deterioration in taste. In this period we find the pictographic writing clearly developed, with a hieratic or cursive script derived from it, adapted for writing with pen and ink. The Middle Minoan period came to an end about 1600 B.C.

Late Minoan I shows a continuation of the taste for realism. Its pottery is distinguished from that of the preceding period by the convention that its designs as a rule are painted dark on a light background: in Middle Minoan III they are painted light on a dark background. Linear writing is now developed. The palace of Phaestos is rebuilt. Fine frescoes and admirable sculptured vases in steatite are found in this period, to which also belong the oldest remains at Mycenae, namely the famous gold deposits in the shaft tombs. In Late Minoan II the naturalistic figures become conventionalized, and a degeneration in art sets in which continues into Late Minoan III. The foreign imports found at Tell el-Amarna and thus of the time of Ikhnaton, are all of Late Minoan III; this affords a valuable hint for dating this phase of development.

Now while some of the earlier periods shade into one another, like the colours of a rainbow, so that it is difficult to tell where the one ends and the next begins, this is not the case of the latest periods, the changes in which have evidently been produced by violence. The chief manifestation is the destruction of Knossos, which took place, apparently as a result of invasion from the mainland, at the very end of the period known as Late Minoan II: that is to say about 1400 B.C. The inferior style called Late Minoan III—the style which till recent years we had been accustomed to call Mycenaean—succeeded at once and without any intermediate transition to the style of Late Minoan II immediately after this raid. It was evidently the degraded style that had developed in the mainland among the successful invaders, founded upon (or, rather, degenerated from) works of art which had spread by way of trade to the adjacent lands, in the flourishing days of Cretan civilization.

We have seen that in Egyptian tombs of about 1500 B.C. there are to be seen paintings of apparently Cretan messengers and merchants, called by the name of Keftiu, bearing Cretan goods: and in addition we find the actual tangible goods themselves, deposited with the Egyptian dead. In Palestine and elsewhere occasional scraps of

the 'palace' styles come to light. But the early specimens of Cretan art found in these regions are all exotic, just as (to quote a parallel often cited in illustration) the specimens of Chinese or Japanese porcelain exhibited in London drawing-rooms are exotic; and they affect but little the inferior native arts of the places where they are found. It is not till we reach the beginning of Late Minoan III, after the sack of Knossos, that we find Minoan culture actually taking root in the eastern lands of the Mediterranean, such as Cyprus and the adjacent coasts of Asia Minor and Syria. We can hardly dissociate this phenomenon from the sack of Knossos. The very limitations of the area over which the 'Mycenaean' art has been found are enough to show that its distribution was not a result of peaceful trade. Thus, the Hittite domination of Central and Western Asia Minor was still strong enough to prevent foreign settlers from establishing themselves in those provinces: in consequence Mycenaean civilization is there absent. The spread of the debased Cretan culture over Southern Asia Minor, Cyprus, and North Syria, between 1400 and 1200 B.C. must have been due to the movements of peoples, one incident in which was the sack of Knossos 1: and this is true, whether those who carried the Cretan art were refugees from Crete, or were the conquerors of Crete seeking yet further lands to spoil.

In short, the sack of Knossos and the breaking of the Cretan power was an episode—it may be, was the crucial and causative episode—in a general disturbance which the fourteenth to the twelfth centuries B.C. witnessed over the whole Eastern Mediterranean basin. The mutual relations of the different communities were as delicately poised as in modern Europe: any abnormal motion in one part of the system tended to upset the balance of the whole. Egypt was internally in a ferment, thanks to the eccentricities of the crazy dilettante Ikhnaton, and was thus unable to protect her foreign possessions; the nomads of Arabia, the Sutu and Habiru, were pressing from the South and East on the Palestinian and Syrian towns; the dispossessed Cretans were crowding to the neighbouring lands on the north; the might of the Hittites, themselves destined to fall to pieces not long afterwards, blocked progress northward: it is little wonder that disorders of various kinds resulted from the consequent congestion.

It is just in this time of confusion that we begin to hear, vaguely at first, of a number of little nationalities—people never definitely

assigned to any particular place, but appearing now here, now there, fighting sometimes with, sometimes against, the Egyptians and their allies. And what gives these tribelets their surpassing interest is the greatness of the names they bear. The unsatisfying and contemptuous allusions of the Egyptian scribes record for us the 'day of small things' of people destined to revolutionize the world.

We first meet these tribes in the Tell el-Amarna letters. The king of Alašia (Cyprus) complains that his coasts are being raided by the Lukku, who yearly plunder one small town after another. 1 That indefatigable correspondent, Rib-Addi, in two letters, complains that one Biḫura has sent people of the Sutu to his town and slain certain Sherdan men—apparently Egyptian mercenaries in the town guard. 2 In a mutilated passage in another letter Rib-Addi mentions the Sherdan again, in connexion with an attempt on his own life. Then Abi-Milki reports 3 that 'the king of Danuna is dead, and his brother has become king after him, and his land is at peace'. It is almost the only word of peace in the whole dreary Tell el-Amarna record.

Next we hear of these tribes in their league with the Hittites against Ramessu II, when he set out to recover the ground lost to Egypt during the futile reign of Ikhnaton. 4 With the Hittites were allied people from

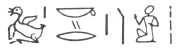

This was in 1333 B.C. On the side of Ramessu fought mercenaries called Šȝrḍȝhȝ (

) no doubt the

) no doubt the

[paragraph continues] Sherdan of whom we have heard already in the Tell el-Amarna letters. These people were evidently ready to sell their services to whomsoever paid for them, for we find them later operating against their former Egyptian masters.

About thirty years later, when Merneptah was on the throne, there was a revolt of the Libyans, and with many allies from the 'Peoples of the Sea' they proceeded to attack Egypt. Though the Philistines do not actually appear among the names of the allies, the history of this invasion is one of the most important in the origines of that remarkable people. The details are recorded in four inscriptions set up by the king after his victory over the invaders, one of which inscriptions is the famous 'Israel' stela.

The first inscription is that of the temple of Karnak, a translation of which will be found in Breasted's Ancient Records, vol. iii, p. 241. This inscription begins with a list of the allied enemies:

[paragraph continues] The beginning of the inscription is lost, but the list is probably complete, as in the sequel, where the allied tribes are referred to more than once, no other names are mentioned.

Merneptah, after extolling his own valour and the military preparations he had made, tells us how he had received news that

(Maraiwi or something similar) 'the miserable chief of Libya', with his allies aforesaid, had come with his family to the western boundary of Egypt. Enraged like a lion, he assembled his officers and to them expressed his opinion of the invaders in a way that leaves nothing to the imagination. 'They spend their time going about and fighting to fill their bellies day by day: they come to Egypt to seek the needs of their mouths: their chief is like a dog, without courage . . . .' Some of the vigorous old king's expressions have been bowdlerised by the hand of Time, which has

(Maraiwi or something similar) 'the miserable chief of Libya', with his allies aforesaid, had come with his family to the western boundary of Egypt. Enraged like a lion, he assembled his officers and to them expressed his opinion of the invaders in a way that leaves nothing to the imagination. 'They spend their time going about and fighting to fill their bellies day by day: they come to Egypt to seek the needs of their mouths: their chief is like a dog, without courage . . . .' Some of the vigorous old king's expressions have been bowdlerised by the hand of Time, which has

deprived us of a course of the inscribed masonry of the temple but notwithstanding we have an admirable description of restless sea-rovers, engaged in constant plunder and piracy. Then Merneptah, strengthened by a vision of his patron Ptah which appeared to him in the night, led out his warriors, defeated the Libyans—whose 'vile fallen chief' justified Merneptah's opinion of him by fleeing, and, in the words of the official report of the Egyptian general to his master, 'he passed in safety by favour of the night . . . all the gods overthrew him for the sake of Egypt: his boasting is made void: his curses have come to roost: no one knows if he be alive or dead, and even if he lives he will never rule again. They have put in his place a brother of his who fights him whenever he sees him'. The list of slain and captives is much mutilated, but is of some importance. For the slain were reckoned by cutting off and counting the phalli of circumcised, the hands of uncircumcised victims. 1 From the classification we see that at the time of the victory of Merneptah, the Libyans were circumcised, while the Shardanu and Shekelesh and Ekwesh, as we may provisionally vocalize the names, were not circumcised. The inscription ends with the flamboyant speech of Merneptah to his court, and their reply, over which we need not linger. Nor do the other inscriptions relating to the event add anything of importance for our present purpose.

About a hundred years later we meet some of these tribes again, on the walls of the great fortified temple of Medinet Habu near Thebes, which Ramessu III, the last of the great kings of Egypt, built to celebrate the events of his reign. These events are recorded in sculptured scenes, interpreted and explained by long hieroglyphic inscriptions. It is deplorable that the latter are less informing than they might have been: we grudge bitterly the precious space wasted in grovelling compliments to the majesty of the victorious monarch, and we would have gladly dispensed with the obscure and would-be poetical style which the writer of the inscription affected. 2

Ramessu III came to the throne about 1200 B.C. 3 Another Libyan invasion menaced the land in his fifth year, but the energetic monarch, who had already been careful to organize the military resources of Egypt, was successful in beating it back. War-galleys

from the northern countries, especially the Purasati and the Zakkala, accompanied the invading Libyans; but this latter element in the assault was only a foretaste of the yet more formidable attack which they were destined to make on Egypt three years later—that is to say, roughly about 1192 B.C.

The inscription describing this war is engraved on the second pylon of the temple of Medinet Habu. Omitting a dreary encomium of the Pharaoh, with which it opens, and a long hymn of triumph with which it ends, we may confine our attention to the historical events recorded in the hieroglyphs, and pictured in the representations of battles that accompany them. The inscription records how the Northerners were disturbed, and proceeded to move eastward and southward, swamping in turn the land of the Hittites, Carchemish, Arvad, Cyprus, Syria, and other places in the sane region. We are thus to picture a great southward march through Asia Minor, Syria, and Palestine. Or, rather, we are to imagine a double advance, by land and by sea: the landward march, which included two-wheeled ox-carts for the women and children, as the accompanying picture indicates; and a sea expedition, in which no doubt the spare stores would be carried more easily than on the rough Syrian roads. Clearly they were tribes accustomed to sea-faring who thus ventured on the stormy Mediterranean; clearly too, it was no mere military expedition, but a migration of wanderers accompanied by their families and seeking a new home. 1

The principal elements in the great coalition are the following:

as well as the Škršȝw, of which we have heard in previous documents.

'With hearts confident and full of plans', as the inscription says, they advanced by land and by sea to Egypt. But Ramessu was ready to 'trap them like wild-fowl'. He strengthened his Syrian

frontier, and at the same time fortified the harbours or river mouths 'with warships, galleys, and barges'. The actual battles are not described, though they are pictured in the accompanying cartoons: but the successful issue of these military preparations is graphically recorded. 'Those who reached my boundary,' says the king, 'their seed is not: their heart and their soul are finished for ever and ever. As for those who had assembled before them on the sea . . . they were dragged, overturned, and laid low upon the beach: slain and made heaps from end to end of their galleys, while all their things were cast upon the water.'

The scenes in which the land and naval engagements are represented are of great importance, in that they are contemporary records of the general appearance of the invaders and of their equipment. The naval battle, the earliest of which any pictorial record remains, is graphically portrayed. We see the Egyptian archers sweeping the crews of the invading vessels almost out of existence, and then closing in and finishing the work with their swords; one of the northerners’ vessels is capsized and those of its crew who swim to land are taken captive by the Egyptians waiting on the shore. In later scenes we see the prisoners paraded before the king, and the tale of the victims—counted by enumerating the hands chopped off the bodies.

The passage in the great Harris Papyrus, which also contains a record of the reign of Ramessu III, 1 adds very little to the information afforded us by the Medinet Habu inscription. The 'Danaiuna' are there spoken of as islanders. We are told that the Purasati and the Zakkala were 'made ashes', while the Shekelesh (called in the Harris Papyrus Shardani, who thus once more appear against Egypt) and the Washasha were settled in strongholds and bound. From all these people the king claims to have levied taxes in clothing and in grain.

As we have seen, the march of the coalition had been successful until their arrival in Egypt. The Hittites and North Syrians had been so crippled by them that Ramessu took the opportunity to extend the frontier of Egyptian territory northward. We need not follow this campaign, which does not directly concern us: but it has this indirect bearing on the subject, that the twofold ravaging of Syria, before and after the great victory of Ramessu, left it weakened and opened the door for the colonization of its coast-lands by the beaten remnant of the invading army.

Ramessu III died in or about 1167 B.C., and the conquered tribes

began to recover their lost ground. For that powerful monarch was succeeded by a series of weak ghost-kings who disgraced the great name of Ramessu which, one and all, they bore. More and more did they become puppets in the hands of the priesthood, who cared for nothing but enriching the treasures of their temples. The frontier of Egypt was neglected. Less than a hundred years after the crushing defeat of the coalition, the situation was strangely reversed, as one of the most remarkable documents that have come down to us from antiquity allows us to see. This document is the famous Golénischeff papyrus, now at St. Petersburg. But before we proceed to an examination of its contents we must review the Egyptian materials, which we have now briefly set forth, a little more closely.

The names of the tribes, with some doubtful exceptions, are easily equated to those of peoples living in Asia Minor. We may gather a list of them out of the various authorities which have been set out above, adding to the Egyptian consonant-skeleton a provisional vocalization, and remembering that r and l are interchangeable in Egyptian:

|

|

|

Tell el-Amarna |

Ramessu II |

Merneptah |

Ramessu III |

|

|

|

c. 1400 B.C. |

1333 B.C. |

c. 1300 B.C. |

c. 1198 B.C. |

|

1. |

Lukku |

X |

X |

X |

- |

|

2. |

Sherdanu |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

3. |

Danunu |

X |

- |

- |

X |

|

4. |

Dardanu |

- |

X |

- |

- |

|

5. |

Masa |

- |

X |

- |

- |

|

6. |

Mawuna or Yaruna (?) |

- |

X |

- |

- |

|

7. |

Pidasa |

- |

X |

- |

- |

|

8. |

Kelekesh |

- |

X |

- |

- |

|

9. |

Ekwesh |

- |

- |

X |

- |

|

10. |

Turisha |

- |

- |

X |

- |

|

11. |

Shekelesh |

- |

- |

X |

X |

|

12. |

Pulasati |

- |

- |

- |

X |

|

13. |

Zakkala |

- |

- |

- |

X |

|

14. |

Washasha |

- |

- |

- |

X |

An X denotes 'present in', a - 'absent from' the lists. The majority of these fourteen names too closely resemble names known from classical sources for the resemblance to be accidental. It will be found that almost every one of these names can be easily identified with the name of the coast dwellers of Asia Minor; and vice versa, with one significant exception, the coast-land regions of Asia Minor are all to be found in recognizable forms in the Egyptian lists. The -sha or -shu termination is to be neglected as an ethnic formative.

Thus, beginning with the Hellespont, the Troas is represented in the Turisha, who have been correctly identified with the future Tyrrhenians (Tursci) as are the Pulasati with the future Philistines.

[paragraph continues] Dardanus in the Troad is represented by the Dardanu. They are the carriers of the Trojan traditions to Italy. 1 Mysia is represented by the Masa, Lydia by the Sherdanu from the town of Sardis. These are the future Sardinians. And the more inland region of Maeonia is echoed in the Mawuna, if that be the correct reading. We now come to a gap: the Carians, at the S.V. corner of Asia Minor, do not appear in any recognizable form in the list, except that the North Carian town of Pedasus seems to be echoed by the Pidasa. To this hiatus we shall return presently. The Lycians are conspicuous as the Lukku.

The name of the sea-coast region of Pamphylia is clearly a later appellation, expressive of the variety of tribes and nationalities which has always characterized the Levant coast. The inland Pisidian town of Sagalassus finds its echo in the Shekelesh. The Cilicians are represented by the Kelekesh, and this brings us to the corner between Asia Minor and North Syria.

The only names not represented in the foregoing analysis are the Danunu, Ekwesh, and the three tribes which first appear in the Ramessu III invasion, the Pulasati, Zakkala, and Washasha. The first two of these, it is generally agreed, are to be equated to the Danaoi and the Achaeans 2—the first appearance in historic record of these historic names. The latter do not appear in the Ramessu III lists: there were no Achaeans in the migration from Asia Minor. The Pulasati are unquestionably to be equated to the future Philistines, north of whom we find later the Zakkala settled on the Palestinian coast. The Washasha remain obscure, both in origin and fate; but a suggestion will be made presently regarding them. They can hardly have been the ancestors of the Indo-European Oscans.

The various lines of evidence which have been set forth in the preceding pages indicate Crete or its neighbourhood as the probable land of origin of this group of tribes. They may be recapitulated:

(1) The Philistines, or a branch of them, are sometimes called Cherethites or Cretans.

(2) They are said to come from Caphtor, a name more like Keftiu than anything else, which certainly denotes a place where the Cretan civilization was dominant.

(3) The hieratic school-tablet mentions 'Akašou' as a Keftian name: it is also Philistine [Achish].

To this may be added the important fact that the Phaestos disk, the inscription on which will be considered later in this book, shows us among its signs a head with a plumed head-dress, very similar to that shown on the Philistine captives represented at Medinet Habu.

We must not, however, forget the fact at which we paused for a moment, that thrice the Philistine guard of the Hebrew kings are spoken of as the Carians; and that the Carians are not otherwise represented in the lists of Egyptian invaders. We are probably not to confine our search for the origin of the Zakkala-Philistine-Washasha league to Crete alone: the neighbouring strip of mainland coast probably supplied its contingent to the sea-pirates. The connexion of Caria with Crete was traditional to the time of Strabo; 'the most generally received account is that the Carians, then called Leleges, were governed by Minos, and occupied the islands; then removing to the continent, they obtained possession of a large tract of sea-coast and of the interior, by driving out the former occupiers, who were for the greater part Leleges and Pelasgi.' 1 Further, he quotes Alcaeus's expression, 'shaking a Carian crest,' which is suggestive of the plumed head-dress of the Philistines. Again, speaking of the city Caunus, on the shore opposite Rhodes, he tells us that its inhabitants 'speak the same language as the Carians, came from Crete, and retained their own laws and customs' 2—which, however, Herodotus 3 contradicts. Herodotus indeed (loc. cit.) gives us the same tradition as Strabo regarding the origin of the Carians: they

'had come from the islands to the continent. For being subjects of Minos, and anciently called Leleges, they occupied the islands without paying any tribute, so far as I can find by inquiring into the remotest times; but whenever Minos required them, they manned his ships; and as Minos subdued an extensive territory, and was successful in war, the Carians were by far the most famous of all nations in those times. They also introduced three inventions which the Greeks have adopted; of fastening crests on helmets, putting devices on shields, and putting handles on shields. . . . After a long time the Dorians and Ionians drove the Carians out of the islands and so they came to the continent. This is the account that the Cretans give of the Carians, but the Carians do not admit its correctness, considering themselves to be autochthonous inhabitants of the continent . . . and in testimony of this they show an ancient temple of Zeus Carios at Mylasa.'

If then by the Pulasati we are to fill in the hiatus in the list of Asia Minor coast-dwellers, the most reasonable explanation of the name is after all the old theory that it is to be equated with Pelasgi. And if the worshippers of Zeus Carios settled in Palestine, they might be expected to bring their god with them and to erect a temple to him. Now we read in 1 Samuel vii, that the Philistines came up against the Israelites who were holding a religious ceremony in Mizpah; that they were beaten back by a thunderstorm, and chased in panic from Mizpah to a place called Beth-Car (v. 11). We may suppose that the chase stopped at Beth-Car because it was within Philistine territory; but unfortunately all the efforts to identify this place, not otherwise known, have proved futile. Very likely it was not an inhabited town or village at all, but a sanctuary: it was raised on a conspicuous height (for the chase stopped under Beth-Car): and the name means House of Car, 1 as Beth-Dagon means House or Temple of Dagon. This obscure incident, therefore, affords one more link to the chain.

If the Cretans and the Carians together were represented by Zakkala-Pulasati-Washasha league, we might expect to find some elements from the two important islands of Rhodes and Carpathos, which lie like the piers of a bridge between Crete and the Carian mainland. And I think we may, without comparisons too far-fetched, actually find such elements. Strabo tells us 2 that a former name of Rhodes was Ophiussa: and we can hardly avoid at least seeing the similarity between this name and that of the Washasha. 3 And as for Carpathos, which Homer calls Crapathos, is it too bold to hear in this classical name an echo of the pre-Hellenic word, whatever it may have been, which the Egyptians corrupted to Keftiu, and the Hebrews to Caphtor? 4

What then are we to make of the name of the Zakkala or Zakkara? This has hitherto proved a crux. Petrie identifies it with Zakro in Crete 5; but as has several times been pointed out regarding this identification, we do not know how old the name Zakro may be. As we have seen that all the other tribes take their name

from the coasts of Asia Minor, it is probable that the Zakkala are the Cretan contingents to the coalition: and it may be that in their name we are to see the interpretation of the mysterious Casluhim of the Table of Nations 1 (כסלחים being a mistake for סכל׳). The most frequently suggested identification, with the Teucrians (assigned by Strabo on the authority of Callinus to a Cretan origin), is perhaps the most satisfactory as yet put forward; notwithstanding the just criticism of W. Max Müller 2 that the double k and the vowel of the first syllable are difficulties not to be lightly evaded. Clerinont-Ganneau 3 would equate them to a Nabatean Arab tribe, the Δαχαρηνοί, mentioned by Stephanus of Byzantium; but, as Weill 4 points out, it is highly improbable that one of the allied tribes should have been Semitic in origin; if the similarity of names be more than an accident, it is more likely that the Arabs should have borrowed it.

The conclusion indicated therefore is that the Philistines were a people composed of several septs, derived from Crete and the southwest corner of Asia Minor. Their civilization, probably, was derived from Crete, and though there was a large Carian element in their composition, they may fairly be said to have been the people who imported with them to Palestine the memories and traditions of the great days of Minos.

Footnotes

1:1 In Amos ix. 7 and in the Kethībh of 1 Chron. xiv. 10. The almost uniform rendering of the Greek version (Φυλιστιείμ) seems rather to favour this orthography. The spelling of the first syllable, Φυ, shows, however, that the modern punctuation with the shva is of later growth, and that in the time of the Greek translation the pronunciation still approximated rather to the form of the name as it appears in Egyptian monuments (Purasati).

2:1 Réflexions critiques sur l’origine, l’histoire et la succession des anciens peuples (1747), ii. 254.

2:2 F. Hitzig, Urgeschichte and Mythologie der Philister, Leipzig, 1845.

2:3 Gesenius, Thesaurus, s.v.

2:4 Movers, Untersuchungen über die Religion and die Gottheiten der Phönizier (1841), vol. i, p. 9.

2:5 Except (a) in the Hexateuch, where it is always transliterated Φυλιστιείμ, sometimes Φυλιστιίμ or Φιλιστιείμ; (b) in Judges x. 6, 7, 11, xiii. 1, 5, xiv. 2, where again we find the word transliterated: in some important MSS. however, including Codex Alexandrinus, ἀλλόφυλοι, is used in these passages; (c) in Isa. ix. 11 (English ix. 12, where we find the curious rendering Ἕλληνας, possibly indicating a variant reading in the text that lay before the translators.

3:1 Die alttest. Namen der Bevölkerung, p. 4; adopted by Arnold in Ersch and Gruber's Encyclopaedia, s. v. Philister.

4:1 Namely Joshua xiii. 2; 1 Sam. iv. 7, vii. 12, xiii. 20, xvii. 51, 52; 2 Sam. v. 19, xxi. 12, 17; 1 Chron. xi. 13; 2 Chron. xxi. 16.

4:2 For fuller particulars see Skinner's Commentary on Genesis (pp. 200–214). Sayce finds Caphtor and Kasluhet on an inscription at Kom Ombo: see Hastings's Dictionary, s. v. Caphtor; and Man, 1903, No. 77. But see also Hall's criticisms, ib. No. 92.

6:1 Such are Χαρρι, Χαρεθθι, Χελθι, Χελθει, Χελβει, Χελβες, Χελεμα, Χελεθθι, Χελλεθι, Χελεθιι, Χελεθοι, Χελοθθι, Χολθει, Χολλεθι, Χορεθι, Χορεθθει, Χορρι, Χορρει, Χερεθει, Χερηθει, Χερετ, Χερεθθει, Χερεθιν, Χερεοι, Χωρι, Χερηθη, Χερηθει, Χετθει, Χεττει, Οχελεθθι, Οχερεπι, Οχελβι, Χκελμι, Οχελεθ, Ρεθθι. The Pelethites appear under equally strange guises: Φελετι, Φελτι, Φελτει, Φελετιι, Φελεττει, Φελεθθι, Φελεθθιι, Φελεθθει, Φελετθει, Φελελεθθι, Ουπετ, Οχετ, Οφελτι, Οφελθι, Οφελεθθιι, Οφελετθει, Ωφελεθθει, Οπελθι, Οπελεθιν, Οπερετ, Πελεβι, Οθεθιι, Χετταιοις.

6:2 Cornill, Das Buch des Proph. Ezek. p. 368, followed by Toy, Ezekiel (in Sacred Books of O. T.), p. 88.

6:3 Possibly the instinct for triliteralism may also have been instrumental in the evolution of this form.

6:4 It is given in Lakemacher, Observationes Philologicae (1729), ii. 38, and revived by Ewald in his Kritische Grammatik der hehrläischen Sprache (1827), p. 297.

6:5 Hdt. ii. 128.

7:1 The Greek version has Χερεθί in the first of these passages, in the others Χορρι with a number of varieties of spelling, Χορρει, Χοριν, &c., all of them showing o as the first vowel.

7:2 Journal of the British School at Athens, viii (1901-2), p. 157.

8:1 The name of this chieftain's land is mutilated (tyn’y). Mr. Hall (op. cit. p. 167, Oldest Civilisation of Greece, p. 163) restores Yantanay, and renders 'Cyprus'. W. Max Müller compares with this name the word Adinai, found in the List of Keftian names given on p. 10.

8:2 For these tombs see Hall, British School at Athens, vol. x (1903–4), p. 154, and Proc. Soc. Bib. Arch. xxxi, Plate XVI [Sen-mut]; Wilkinson, Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians, i, Plate II, AḄ. [Rekhmara]; Virey, Mémoires de la mission en Caire, v, p. 7 [Rekhmara], p. 197 ff [Menkheperuseneb]. In the last-named, Keftiu is translated and indexed 'Phénicie'.

10:1 See the brief summary of the various stages of Cretan culture during the Bronze Age, later in the present chapter.

10:2 See Spiegelberg, Zeitschrift fur Assyriologie (1893), viii. 385 (where the text is published incompletely), and W. Max Müller in Mittheilungen der vorderasiatischen Gesellschaft, vol. v, p. 6, where facsimiles will be found.

11:1 Dissertations qui peuvent servir de prolegomenes de l’écriture sainte (1720), II. ii, p. 441.

12:1 A place which, as has often been noticed, has the same radicals as the name of the Philistines.

12:2 Lehrbuch d. bibl. Geschichte, vol. i.

12:3 Aegypten and des Buch Mose, p. 127 ff.

12:4 Asien and Europa, p. 337.

12:5 An elaborate refutation of the Cilician hypothesis will be found in Noordtzij, De Filistijnen, p. 31.

13:1 Zeitschr. für wissensch. Theologie, xxxiv (1891), p. 103.

13:2 Gesch. des Volk. Isr. i. 142.

13:3 Geschiedenis van den Godsdienst in de Oudheid, i. pp. 214, 241.

15:1 'Iudaeos Creta Insula profugos nouissima Libyae insedisse memorant, qua tempestate Saturnus ui Iouis pulsus cesserit regnis.'

15:2 Stephanus of Byzantium, s. v. ….

15:3 The bare outline statement, which is all that is necessary here, can be supplemented by reference to any of the numerous books that have appeared recently on the special subject of Cretan excavation: such as Professor Burrows's pleasantly. written work entitled The Discoveries in Crete (London, Murray, 1907), which contains a most useful bibliography.

16:1 See Hall, Proc. Soc. Biblical Archaeology, xxxi, pp. 144–148.

18:1 Other causes were at work producing the same result of restlessness among the peoples. Thus Mr. Alton suggests to me that the collapse of the island of Thera must have produced a considerable disturbance of population in the neighbouring lands.

19:1 T.A. Letters, ed. Winckler, No. 28; ed. Knudtzon, No. 38.

19:2 ib. W. 77, K. 123. See also W. 100.

19:3 ib. W. 151, K. 151.

19:4 For an exhaustive study of the great battle of Kadesh between Ramessu and the united tribes, see Breasted, The Battle of Kadesh (Univ. of Chicago Decennial Publications, Ser. I, No. 5.

21:1 See W. Max Müller's important note in Proc. Soc. Bib. Arch. x, pp. 147–154, where reasons are given against the exactly opposite interpretation, followed by 1 many authorities (e. g. Breasted, Ancient Records). On the other hand the contrary practice seems to be indicated by 1 Sam. xviii. 25. The difficulty of rendering lies in the fact that we have to deal with Egyptian words not found elsewhere.

21:2 See Breasted, Ancient Records, iv, pp. 1–85.

21:3 Petrie says 1202, Breasted 1198.

22:1 The details of these sculptures are more fully described later in this book.

23:1 Breasted, op. cit. p. 201.

25:1 Turisha has also been identified with the Cilician town of Tarsus.

25:2 With reservations: see Weill, Revue archéologique, sér. IV, vol. iii, p. 67. And even the identification of the Danaoi is uncertain. It is at least improbable that Rib-Addi of Tyre, in the letter quoted above, should report on the peacefulness of so remote a people as the Danaoi.

26:1 Strabo, XIV. ii. 17.

26:2 Strabo, xiv. ii. 3.

26:3 i. 17–1.

27:1 Βαιθχόρin the Greek Version (in some MSS. -κορ). Cf. the first footnote on p. 7.

27:2 xiv. ii. 7.

27:3 Hall looks for the Washasha in Crete, and finds them in the name of the Cretan town Ϝάξος [Oldest Civilization of Greece, p. 177]. But if this comparatively obscure Cretan name were really represented in the Egyptian lists, we might reasonably look for the more important names to appear also. The name appears (in the form Oašašios) in an inscription from Halicarnassus: see Weill in Revue archéologique, sér. IV, vol. iii, p. 63.

27:4 Baur, Amos, p. 79, has already suggested this identification.

27:5 Proc. Soc. Bib. Arch., 1941, p. 41.

28:1 Gen. x. 14.

28:2 Mittheil. der corderas. Gesellschaft, v, p. 3. On Teucer see Frazer, Adonis, Allis, Osiris, p. 112.

28:3 Recueil d’Archéologie orientale, iv. 230.

28:4 loc. cit. p. 64.