The Philistines, by R.A.S. Macalister, [1913], at sacred-texts.com

CHAPTER IV

THE CULTURE OF THE PHILISTINES

I. Their Language.

Of the language of the Philistines we are profoundly ignorant. An inscription in their tongue, written in an intelligible script, would be one of the greatest rewards that an explorer of Palestine could look for. As yet, the only materials we have for a study of the Philistine language are a few proper names, and possibly some words, apparently non-Semitic, embedded here and there in the Hebrew of the Old Testament. Thus, our scanty information is entirely drawn from foreign sources. We are exactly in the same position as a student of some obscure Oriental language would be, if his only materials were the names of natives as reported in English newspapers. Now, we are all familiar with the barbarous and meaningless abbreviation 'Abdul', applied with various depreciatory epithets to a certain ex-potentate. Some time ago a friend called my attention to a paragraph in, I think, a Manchester paper, describing how a certain Arab 'named Sam Seddon' had been prosecuted for some offence: though the 'Arabian Nights' is almost an English classic, the reporter had failed to recognize the common name Shems ed-Din! If we were obliged to reconstruct the Arabic language from materials of this kind, we could hardly expect to get very far; but in attempting to recover something of the Philistine language we are no better off.

The one common noun which we know with tolerable certainty is ṣeren, the regular word in the Hebrew text for the 'lords' by which the Philistines were governed: a word very reasonably compared with the Greekτύραννος. 1 This, however, does not lead us very far. It happens that no satisfactory Indo-European etymology has been found for τύραννος, so that it may be a word altogether foreign to the Indo-European family. In any case, one word could hardly decide the relationship of the Philistine language any more than

could 'benval' (sic!) decide the relationship of Pictish in the hands of Sir Walter Scott's amateur philologists.

The word ṣeren is once used (1 Kings vii. 30) as a technical term for some bronze objects, part of the 'bases' made for the temple (wheel-axles?). This is probably a different word with different etymological connexions. The word mekōnah in the list cited below, is found in the same verse.

Renan, in his so-called Histoire du peuple d’Israël, has collected a list of words which he suggests may have been imported into Hebrew from Philistine sources. That there should be such borrowing is a priori not improbable: we have already shown that the leaders among Hebrew speakers must have understood the Philistine tongue down to the time of David at least. But Renan's list is far from convincing. It is as follows:

mekōnah, something with movable wheels: compare machina.

mekhērah, 'a sword': compare μάχαιρα.

caphtōr, 'a crown, chaplet': compare capital.

pīlegesh, 'a concubine': compare pellex.

A further comparison of the name of Araunah the Jebusite, on whose threshing-floor the plague was stayed (and therefore 'the place in Jerusalem from which pestilential vapours arose'!), with the neuter plural form Averna, need hardly he taken seriously.

But since Renan wrote, the discovery of the inscription on the Black Stone of the Forum has shown us what Latin was like, as near as we can get to the date of the Philistines, and gives us a warning against attempts to interpret supposed Philistine words by comparison with Classical Latin. And, even if the above comparisons be sound, the borrowing, as Noordtzij 1 justly remarks, might as well have taken place the other way; as is known to have happened in several cases which he quotes.

There is a word כובע or קובע meaning a 'helmet', the etymology of which is uncertain. 2 It may possibly be a Philistine word: the random use of כ and ק suggests that they are attempts to represent a foreign initial guttural (cf. ante, p. 75). Both forms are used in 1 Samuel xvii, the one (׳כ) to denote the helmet of the foreigner Goliath, the other (׳ק) that of the Hebrew Saul. No stress can, however, be laid on this distinction. The form ׳ק is used of the helmets of the foreigners named in Ezekiel xxiii. 24, while ׳כ is used of those of Uzziah's Hebrew army, 2 Chronicles xxvi. 14.

Of the place-names mentioned in the Old Testament there is not one, with the possible exception of Ziklag, which can be referred to the Philistine language. All are either obviously Semitic, or in any case (being mentioned in the Tell el-Amarna letters) are older than the Philistine settlement. Hitzig has made ingenious attempts to explain some of them by various Indo-European words, but these are not successful.

The persons known to us are as follows:

(1) Abimelech, the king who had dealings with Abraham. A Semitic name.

(2) Aḫuzzath, Counsellor of No. (1): Semitic name.

(3) Phicol, General of No. (1). Not explained as Semitic: possibly a current Philistine name adopted by the narrator.

(4) Badyra, king of Dor, in Wen-Amon's report. Probably not Semitic.

(5) Warati, a merchant, mentioned by Wen-Amon.

(6) Makamaru, a merchant, mentioned by Wen-Amon.

(7) Dagon, chief god of the Philistines.

(8) Delilah, probably not Philistine. See ante, p. 45.

(9) Sisera, king of Harosheth. See ante, p. 41, and compare Beneṣasira on the tablet of Keftian names.

(10) Achish or Ekosh, 1 apparently the standard Philistine name, like 'John' among ourselves. It seems to reappear in the old Aegean home in the familiar form Anchises. It occurs twice in the tablet of Keftian names (ante, p. 10) and in the Assyrian tablets it appears in the form Ikausu. 2

(11) Maoch, father of Achish, king of Gath. Unexplained and probably Philistine.

(12) Ittai, David's faithful Gittite friend, perhaps Philistine.

(13) Obed-Edom, a Gittite who sheltered the Ark: a pure Semitic name.

(14) Goliath, a Rephaite, and therefore not Philistine.

(15) Saph, a Rephaite, and therefore not Philistine.

(16) Zaggi, a person signing as witness an Assyrian contract tablet of the middle of the seventh century B.C. found at Gezer. The name is not explained, and may be Philistine.

(17–26) The ten Philistine kings mentioned on the Assyrian tablets, who without exception bear Semitic names. Sarludâri is an Assyrian name, which may possibly have been adopted by its bearer as a compliment to his master.

This list is so meagre that it is scarcely worth discussing. It will be observed that at the outside not more than eight of these names can be considered native Philistine.

Down to about the time of Solomon the Philistines preserved their linguistic individuality. A basalt statuette of one Pet-auset was found somewhere in the Delta, 1 in which he is described as an interpreter

'for Canaan and Philistia'. There would be no point in mentioning the two places if they had a common language. Ashdod, we have seen, preserved a patois down to the time of Nehemiah; but it is clear that the Philistines had become semitized by the time of the operations of the Assyrian kings. It is likely that the Rephaite element in the population was the leaven through which the Philistines became finally assimilated in language and other customs to the surrounding Semitic tribes, as soon as their supremacy had been destroyed by David's wars. The Rephaites, of course, were primarily a pre-Semitic people: but probably they had themselves already become thoroughly semitized by Amorite influence before the Philistines appeared on the scene.

'for Canaan and Philistia'. There would be no point in mentioning the two places if they had a common language. Ashdod, we have seen, preserved a patois down to the time of Nehemiah; but it is clear that the Philistines had become semitized by the time of the operations of the Assyrian kings. It is likely that the Rephaite element in the population was the leaven through which the Philistines became finally assimilated in language and other customs to the surrounding Semitic tribes, as soon as their supremacy had been destroyed by David's wars. The Rephaites, of course, were primarily a pre-Semitic people: but probably they had themselves already become thoroughly semitized by Amorite influence before the Philistines appeared on the scene.

We have, besides, a number of documents which, when they have been deciphered, may help us in reconstructing the 'speech of Ashdod'. The close relationship of the Etruscans to the Philistines suggests that the Etruscan inscriptions may some time be found to have a bearing on the problem. It is also not inconceivable that some of the obscure languages of Asia Minor, specimens of which are preserved for us in the Hittite, Mitannian, Lycian, and Carian inscriptions may have light to contribute. The inscriptions of Crete, in the various Minoan scripts, and the Eteocretan inscriptions of Praesos 2 may also prove of importance in the investigation. Two other alleged fragments of the 'Keftian' language are at our service: the list of names already quoted on p. 10, which suggestively contains Akašou and Beneṣasira: and a magical formula in a medical MS. of the time of Thutmose III, published by Birch in 1871, 3 which contains

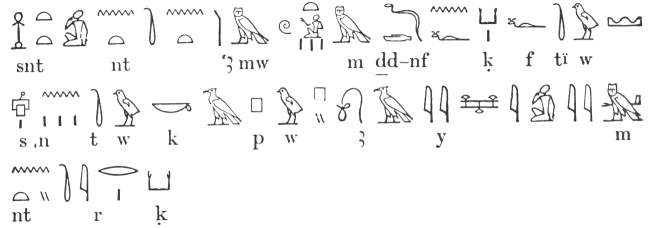

inter alia the following—copied here from a corrected version published by Ebers. 1

'Conjuration in the Amu language which people call Keftiu—senutiukapuwaimantirek' or something similar. This is not more intelligible than such formulae usually are. Mr. Alton calls my attention to the tempting resemblance of the last letters to trke, turke, θrke, a verb (?) common in the Etruscan inscriptions.

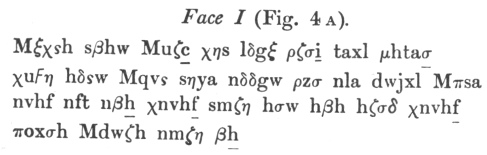

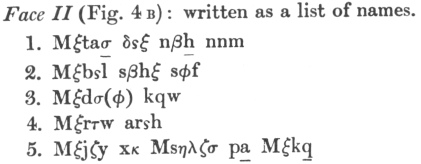

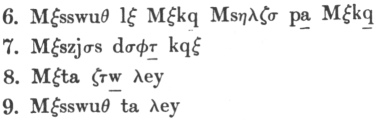

There is one document of conspicuous importance for our present purpose, although it is as yet impossible to read it. This is the famous disk of terra-cotta found in the excavation of the Cretan palace of Phaestos, and dated to the period known as Middle Minoan III—that is to say, about 1600 B.C. It is a roughly circular tablet of terra cotta, 15.8–16.5 cm. in diameter. On each face is a spiral band of four coils, indicated by a roughly drawn meandering line; and an inscription, in some form of picture-writing, has been impressed on this band, one by one, from dies, probably resembling those used by bookbinders. I suppose it is the oldest example of printing with movable types in the world. On one face of the disk, which I call Face I, there are 119 signs; on the other face, here called Face II, there are 123. They are divided into what appear to be word-groups, 30 in number on Face I and 31 on Face II, by lines cutting across the spiral bands at right angles. These word-groups contain from two to seven characters each. There are forty-five different characters employed. It is likely, therefore, from the largeness of this number that we have to deal with a syllabary rather than an alphabet.

I have discussed this inscription in a paper contributed to the Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 2 to which I must refer the reader for the full investigation. Its special importance for our present purpose is based upon the fact that the most frequently used character, a man's head with a plumed head-dress, has from the

moment of its first discovery been recognized as identical in type with the plumed head-dresses of the Philistine captives pictured at Medinet Habu. This character appears only at the beginnings of words, from which I infer that it is not a phonetic sign, but a determinative, most probably denoting personal names. Assuming this, it next appears that Face II consists of a list of personal names. Representing

Click to enlarge

Fig. 4 A. The Phaestos Disk (Face 1).

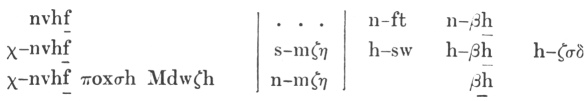

each character by a letter, which is to be regarded as a mere algebraic symbol and not a phonetic sign, we may write the inscription on the disk in this form:

Click to enlarge

Fig. 4B. The Phaestos Disk (Face II).

There is just one type of ancient document which shows such a 'sediment', so to speak, of proper names at the end. This is a contract tablet, which ends with a list of witnesses, and in the paper above

referred to I have put forward the conjecture that the disk is of this nature. In Face I, although not one word of the inscription can be deciphered, it will be found that, applying the clue of the proper names, everything fits exactly in its place, assuming the ordinary formula of a contract such as we find it in cuneiform documents.

The first two words would give us the name and title of the presiding magistrate: then comes the name of one of the contracting parties, uζc χηs: then come six words or word-groups, quite unintelligible, but not improbably stating what this person undertakes to do: then follows what would be the name of the other contracting party.

Next come some words which ought to give some such essential detail as the date of the contract. And we find among these words just what we want, a proper name πsa, denoting the officer who was eponymous of the year.

The last thirteen words we might expect to be a detailed inventory of the transaction, whatever its nature may have been. It is therefore satisfactory to notice that they arrange themselves neatly, just as they stand, in three parallel columns, having obvious mutual relations: thus—

which table not only confirms the conclusions arrived at, but illustrates a rule that may also be inferred from the list of witnesses on Face II. Words are declined by prefixes ξ, s, n, h, χ and suffixes w, ξ; and words in apposition have the same prefix. See the third column of the above table, and the titles of witnesses 1, 2. We have a word βh in several forms: s-βh-w, n-βh, h-βh, s-βh-ξ. Further, ξ, prefixed to the 'name of the magistrate' and all the names of witnesses, probably means 'before, in the presence of'. The name which follows that of the two witnesses 5 and 6 is probably that of their father, and this assumed it follows that the prefix s probably has a genitive sense.

There remains one important point. At the bottom of certain characters there is a sloping line running to the left. This is always at the end of a word-group: the two apparent exceptions shown in some drawings of the disk (in word-groups 6 and 23 on Face II) being seemingly cracks in the surface of the disk. The letters marked are underlined in the transcript given above. I suggest with regard to

these marks that they are meant to express a modification of the phonetic value of the character, too slight to require a different letter to express it, but too marked to allow it to be neglected altogether. And obviously the most likely modification of the kind would be the elision of the vowel of a final open syllable. The mark would thus be exactly like the virāma of the Devanāgarī alphabet. 1 When we examine the text, we find that it is only in certain words that this mark occurs. It is found in βh, however declined, except when the suffixes w, ξ are present. It is found in the word nvhf, however declined, and appears in the two similar words µhtaσ and Mξtaσ. It is found in the personal name kq (in the formula pa Mξkq). There are only one or two of the eighteen examples of its use outside these groups, and probably if we had some more examples of the script, or a longer text, these would be found to fit likewise into series. This stroke would therefore be a device to express a final closed syllable. Thus, if it was desired to write the name of the god Dagon, it would be written on this theory, let us say, DA-GO-NA, with a stroke underneath the last symbol to elide its vowel. The consequences that may follow if this assumption should at any time be proved, and the culture which the objects represented by the various signs indicate, are subjects for discussion in later sections of this chapter. For further details of the analysis of the disk I must refer to my Royal Irish Academy paper above quoted: I have dwelt on it here, because if, as is most probable, the plumed head-dress shows that in this disk we have to deal with 'proto-Philistines', we must look to this document and others of the same kind, with which excavators of the future may be rewarded, to tell us something of the language of the people with whom we have to deal.

Footnotes

79:1 The 'Lords of the Philistines' are, however, in the Greek Version called σατράπαι; but in Judges (except iii. 3), Codex Vaticanus and allied MSS. have ἄρχοντες, a rendering also found sometimes in Josephus.

80:1 De Filistijnen, p. 81.

80:2 Cf. Latin cappa, &c. (?).

81:1 Max Müller in his account of the school-tablet (ante, p. 10) compares the Assyrian form Ikausu and the Greek Ἀγχοῦς, and infers that the true pronunciation of the name was something like Ekôsh.

81:2 But in the last edition of KAT. p. 437, it is noticed that this name can possibly be read Ikasamsu or Ikasamsu.

82:1 See the description by Chassinat, Bulletin de l’inst. franç. d’arch. au Caire, i. (1901), p. 98.

82:2 See Conway in the Annual of the British School at Athens, vol. viii, p. 125, for an exhaustive analysis of these inscriptions.

82:3 Zeitschr. f. ägypt. Sprache (1871), p. 61.

83:1 Zeitschr. der D. M. G. xxxi, pp. 451, 452.

83:2 Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, vol. xxx, section C, p. 342.

87:1 I find that this comparison has been anticipated in an article in Harper's Magazine (European Edition, vol. lxi, p. 187), which I have read since writing the above. The rest of the article, I regret to say, does not convince me.