The Evil Eye, by Frederick Thomas Elworthy, [1895], at sacred-texts.com

The Evil Eye, by Frederick Thomas Elworthy, [1895], at sacred-texts.com

WHETHER looked at as the emblem of a hideous fable or simply as a mask, the Gorgoneion has in all ages been "reputed one of the most efficacious

Click to enlarge FIG. 47. |

It may have been the universality of the belief in the Medusa's power that led to masks becoming such favourites as protectors. Probably the root idea of the efficacy of any amulet lying in its strangeness, whether provocative of fear or laughter, may have led to the grotesque and impossible faces which are so frequently to be seen. Actors in classic days adopted a mask to hide their features, most likely from the general dread of the evil eye, lest among the crowd, gazing upon the performer, some may

have possessed that fatal influence which Heliodorus records respecting the daughter of Calasiris. The masks, whether worn by actors or painted on walls by way of decoration, were commonly of hideous grotesqueness. In Rome, certain of these by long usage developed into conventional faces, just like

Click to enlarge FIG. 48. |

speak for themselves, showing how the idea had developed from the ugliness of the early Greek ideal, to beauty in the Augustan age of Rome, and how it had again declined both in art and in comeliness during the period of Byzantine Christianity, as exhibited in the annexed (Fig. 49), known as the

Click to enlarge

FIG. 49.

[paragraph continues] "Gnostic Gorgon." The inscription upon this undoubted amulet (actual size) from King's Gnostics 261 (p. 67) being translated, reads: "Holy, holy, Lord of Sabaoth, hosanna in the highest, the Blessed." 262

A Medusa's head very similar to the one last mentioned is given in Gnostics (p. 119) as the seal of S. Servatius, Maestricht Cathedral, which of course brings it

down as an amulet to much later times. We know that both on seals and on coins objects prophylactic against fascination were common even in the late Middle Ages, and were used down to a period long since the Reformation. Our own Anglo-Saxon kings adopted such devices on their coins. 263 Not only were the Greek and Etruscan Gorgons common in Europe, representing a widely-received myth, but in the East, Bhavani, the Destructive Female Principle, is still represented with a head exactly agreeing with the most ancient type of the Medusa: with huge tusks, tongue thrust out, and with snakes twining about the throat, just as may still be seen in the Etruscan tomb of the Volumni at Perugia, and such as was described by Hesiod of old. "In the centre of that tomb 264 is an enormous Gorgon's head, hewn from the dark rock, with eyes upturned in horror, gleaming from the gloom, teeth bristling whitely in the open mouth, wings on the temples, and snakes knotted over the brow. You confess the terror of the image, and almost expect to hear

"Some whisper from that horrid mouth

Of strange unearthly tone;

A wild infernal laugh to thrill

One's marrow to the bone.

But, no! it grins like horrid Death,

And silent as a stone."

A lamp of earthenware was suspended over the doorway of this same chamber, having another Medusa's head on the bottom. A similar lamp was suspended from the ceiling of the central chamber.

The illustration here given is from the under side of a very beautifully wrought bronze lamp in the Museum at Cortona, intended for suspension, and it would seem from these several instances, that this mode of depicting the Gorgon's head was, as we are told, 265 a very common Etruscan sepulchral decoration.

Click to enlarge FIG. 50. |

wings outspread, and a naked satyr playing the double pipes, having a dolphin beneath his feet. "In a band encircling it are lions, leopards, wolves, griffons in pairs, devouring a bull, a horse, a boar, and a stag." The bottom is hollowed in the centre and contains a huge Gorgon's face. "It is a libel on the face of fair Dian, to say that this hideous visage symbolises the moon. . . . There is every reason to believe it was suspended in a tomb, perhaps in a temple as a sacrificial lamp. . . . It is undoubtedly of ante-Roman times, and I think it may safely be referred to the fifth century of Rome, or to the close of Etruscan independence." 266

Gorgon's heads are found also on the cinerary urns, "winged and snaked, sometimes set in acanthus leaves." Some of these, coloured to the life, are now to be seen in the Museum at

Click to enlarge FIG. 51 |

Fig. 51 is from a vase at Chiusi, which Dennis says (vol. ii. p. 221) is typical of the early Etruscan style; but whether the Greeks or the Etruscans first discarded hideousness is uncertain. It is however clear that the latter people had done so before Roman times, for in the same tomb of the Volumni, where the frightful face is on the ceiling, is to be found an "ash chest" with a patera at each angle, having a Gorgon's head, "no longer the hideous

mask of the original idea, but the beautiful Medusa of later art, 267 with a pair of serpents knotted on her head and tied beneath her chin, and wings also springing from her brows." 268

Not only did the pictorial idea change and develop, but as extremes meet, so it came in time to be believed, that it was her marvellous beauty and not her hideousness, that had turned beholders into stone. 269

One of the most beautiful Medusas of late Greek

Click to enlarge

FIG. 52--From Naples Museum.

art is to be seen in Rome. It is a highly sculptured relief in the Villa Ludovisi, where also is the Aurora of Guercino, now unfortunately closed to the public. She is there represented as a woman of severe though grand beauty, in her dying moments. There are no snakes about her head, but her hair lies in suggestive snake-like tresses about her neck and shoulders. Her eyes are closed, but yet she does not appear dead. This beautiful sculpture is ascribed

to the Macedonian period of Greek art. A much later type still is shown in the triskelion arms of Sicily, in the chapter on Crosses (p. 290).

The legend of the Gorgoneion although apparently unknown to the Egyptians is traceable in the far East, whence indeed the story of Perseus is said to have been brought. It is known in Cambodia and Borneo, in Tahiti and in far-off Peru.

Click to enlarge FIG. 53. From Tahiti |

By some it was held long ago that the Gorgon's head was a symbol of the lunar disc, hence the allusion by Dennis to "fair Dian." Another theory has been broached in modern times, that "the Gorgon of antiquity was nothing but an ape or ourang-outang, seen on the African coast by some early Greek or Phœnician mariner; and that its ferocious air, its

horrible tusks, its features and form caricaturing humanity, seized on his imagination, which reproduced the monster in the series of myths." 270

The story of the Medusa is but an incident in the early belief in the evil eye, and should be carefully

Click to enlarge

FIG. 54., 55.

From Peru.

studied by any who are interested in the subject. After using it effectually in the turning of his enemy Polydectes into stone, Perseus presented the terrible head to Pallas, the Athenian goddess, who placed it on her aegis, and in nearly all her statues, and those of her Roman counterpart Minerva, she bears this notable mask as an amulet. 271

Originally the aegis was a goat's hide worn as a protective garment, but later it became a breastplate, and afterwards a shield. When Minerva is represented with a shield as the war goddess, she has the gorgon's head emblazoned upon it. Thus was

first set the fashion of bearing some prophylactic device by men in battle, which should first attract the angry glance of their enemies and then baffle their malignity. A custom once begun, and by so powerful a deity as the Goddess Athena, would not long want imitators; consequently representations of fighting men, especially on Greek vases, the oldest-known European pictures, show some object or other depicted upon breastplate or shield, but always one that was considered effective as a protector. 272 As the number of protectors came to be more numerous, so the variety of device upon the shield became greater: each warrior-chief naturally adopting that in which he placed the greatest faith. According to Plutarch, Ulysses adopted the dolphin as his special charm; both on his signet and on his shield. It is said that he chose this fish to commemorate the saving of Telemachus from drowning by its means.

Since then the dolphin has become a favourite device, and was in Roman times one of the special charms against the evil eye. 273 On an ancient vase at Arezzo 274 is a representation of Hercules and Telamon fighting the Amazons, who are all armed with round shields. The shield of one of the Amazons bears the Gorgoneion; another who is wounded bears a Cantharus or two-handled cup on her shield, and on her

cuirass a lion. The hero Telamon bears a round shield just like the Amazons with a large lion passant upon it. Each of the figures represented may be taken as a leader, and so of course each of that leader's following would bear the same device. When under the Roman Empire the usages of war had become regulated by minute laws, the distinguishing badges of the various legions were prescribed with great exactness. The devices of several are referred to by Tacitus and also by Ammianus. They were borne by each man on his shield, and fortunately we are still able to see what many of those designs were.

A few of these devices here given (Figs. 56-66) are from Notitia Dignitatum, 275 by Guido Pancirolo, Lugduni, 1608. 276 Of the various subjects adopted by authority as the "cognisances" of the Roman legions, we have made a typical selection. One main idea seems to have influenced the choice of design. In all the scores of representations preserved in this remarkable book nearly all had a symbol of the sun in some form or other as its centre. There are twenty-one different insignia of the Thracian legions, of which sixteen are here given; all but one of the twenty-one had a circle in

its centre. 277 Many had the crescent as well as the sun; and one, the Thaanni, had six stars (probably the Pleiades) enclosed within the crescent.

Click to enlarge

FIG. 56--Auxilia Palatina XVIII. p. 21.

Many of the shields bore various animals as "supporters." These may have been intended to represent the sun, or as symbols of it. 278

Click to enlarge

FIG. 57.--Legiones Comitatenses XXI. p. 36 (Thracians)

In the descriptions given, it is quite clear that the colours, as well as the devices, had each their symbolic meaning. 279 The Ascarii Seniores had their shield half white and the rest ferruginea. There were two purple hemicycles united in the

Click to enlarge

FIG. 58.--Legiones Palatinæ XV. p. 20.

centre with two half-circles. Pancirolo calls the whole a skilful design of symbol (arguta symboli inventio), for purple is the imperial colour.

The description of the insignia of the Ascarii in which the above occurs, if it had been in modern heraldic language, might well apply to mediæval coats. 280

We are told that the Honoriani Seniores (cavalry) bore a white shield, in which a golden centre (aureus umbilicus) was surrounded by a yellow circle.

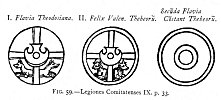

Click to enlarge

FIG. 59.--Legiones Comitatenses IX. p. 33.

[paragraph continues] The Martiarii Seniores had two jackals rampant supporting an orb with a Greek cross, surmounted by a crescent. The Cornuti had two griffins' heads joined

Click to enlarge FIG 60. Auxilia Palatina |

could not have been intended to distinguish any leader from his following. They give plenty of examples of both helmets and shields. None of the helmets had visors, which appeared at a much later period, while the shields had

Click to enlarge

FIG. 61.--Auxilia Palatina XVIII. p. 30.

(All the foregoing belong to the Army of the East.)

a common device for each clan or troop--of these by. far the most frequently seen was the Gorgoneion. The various ancient representations

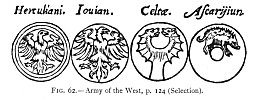

Click to enlarge

FIG. 62.-- Army of the West, p. 124 (Selection).

of objects depicted on shields seem to show that these were adopted at the special or separate pleasure of the individual chieftains, and the device may be said to depict his clan totem. They were, like the cognizances of our mediæval knights in their day, not specially distinctive of family, but more like the Roman insignia, the badges of particular corps. Thus, according to Æschylus, in a

story dating from the dawn of history, the heroes at the siege of Thebes bore distinctive devices on their shields, which the poet describes, and we may at least accept his statements as of historic value.

Click to enlarge

FIG. 63.--Army of the West, p. 125.

[paragraph continues] One, Parthenopæus, had on his shield a sphinx devouring a prostrate Theban; another, Typhon (our devil) belching forth flames and smoke. The mention of a sphinx as a device naturally leads one to Egypt, but there is a remarkable absence of anything

which could be called a cognizance upon the arms of ancient Egypt, so that we of course conclude

Click to enlarge

FIG. 64.--Army of the West, p. 127.

that in this particular the Greeks obtained their notions elsewhere. 282

The variety of devices upon Chinese shields, and the known unchangeable antiquity of everything in China, make it a fair assumption that the early Greeks and Etruscans obtained the custom of painting

Click to enlarge

FIG. 65.--Army of the West, p. 125.

their shields from oriental people, and not from Egypt. Among the Japanese, enormous fans are used as ensigns in war, with various devices painted upon them; moreover the armorial bearings, the totems of families, are painted on fans. The fan is

considered as a symbol of life--the rivet end is the starting point, and as the rays expand, so the road of, life widens out. 283 The suggestion that the original custom of emblazoning strange devices upon

Click to enlarge

FIG. 66.--Army of the West, p. 127.

warriors' shields, to catch the eye of the enemy, is an Oriental one, lends additional weight to the contention that in the Medusa's head we have the germ of armorial device, because, as before mentioned, Bhavani

corresponds to and is most likely the prototype of the Greek Gorgon, whereas there is no evidence of anything analogous in ancient Egyptian mythology.

Having then, as we believe, run the original idea to its source, it is easy to see how it became adopted practically. The belief in the power of the malignant eye, especially of a furious foe, needed something to be held up before it, which should absorb the poison of the first glance. What then so effective as a strangely attractive pictorial device, to be carried in front of the warrior on his shield, on which might first alight the dreaded eye? It was thought that a protection against the dire invisible blow was a much greater safeguard than the best shield or buckler against the stroke of sword or spear. Hence the habit of presenting a strange sight to the enemy grew and developed until it crystallised into a custom which has endured to this day, but whose origin and meaning have been utterly forgotten.

To continue the chain of evidence, we find the Roman insignia continued down to Norman times. In the long interval between the placing of the Medusa's head upon the ægis of Athena, and even the Greek, or still later Roman age, a great variety of device had been adopted by fighting men, to be painted on their shields. The stranger and more bizarre the design, so much the more potent.

In the Bayeux tapestry, the figures upon the shields of the Norman knights were generally simple and single, carrying on for the most part the style of the Roman shields. This is the more easily accounted for when we remember that the Franks and Gauls had, from Constantine's time onwards, been the chief material of the Roman

armies, and that after the destruction of the Empire, they would be likely to maintain, or at least not to forget, the institutions and traditions of the school in which they had been trained. We therefore expect to find that down to a moderately late period, the arms and discipline of the Franks would perpetuate, in the main, those of their Roman teachers. In another branch of our subject we see how various emblems and simple amulets came to be used not only singly, but compounded and combined, from the most simple to the most various and complicated types, in all intervening stages; so also we find that the devices called armorial bearings became compounded and complicated during the age known as that of Chivalry, until at last a systematic form of such combination developed itself into a quasi-science, which we now call Heraldry. Of course in the meantime the old notion of specially favourite amulets (shall we call them totems?) had become fixed, and thus certain devices had been adopted by heads of families or tribes which their dependants adopted as their own special cognizance, and naturally when families became united by marriage, each party contributed his or her own special family device, and hence arose what is known as "quartering of arms." This having grown into a well-recognised system with its official experts and exponents, the combination of totems, amulets, or special devices, has at length arrived at the position of a pictorial family history, read with greater pride, and, in these enlightened days, more highly valued, than any other records however compiled. It preserves the mark of lineage to the highest and the noblest born, through means which, though retained

and still believed in by humbler people, are treated with scoffing and contempt by those most interested. Superstition and ignorance are the mildest words to express the opinions of the adepts in heraldry, for those who still cherish the root notions on which heraldry is founded. Who are the totemists, who are the really ignorant, but those who boast loudest of their refinement, their cultivation, their enlightenment, as proved by their long pedigree, recorded by amulets?

158:259 King, Gnostics, pp. 67, 223. Lucian says: "It was an amulet against the evil eye: what could be more potent than the face of the Queen of Hell?"

159:260 There are several similar ones, quite flat at the back, and, like this, perforated with holes for suspension, in the Museums of Palermo and Girgenti. They were evidently intended to be hung up against a wall or other flat surface.

160:261 For permission to copy illustrations from the works of the late Rev. C. W. King, I am indebted to the kindness of Mr. David Nutt, and Messrs. G. Bell and Sons.

160:262 Αγιος αγιος κοας φαωθ ωσανας τοις υψιστοις ευλογιμενος. This legend, full of corruptions, is intended for: Ἅγιος, Ἅγιος, Κύριος Σαβαώθ, ὡσαννὰ τοῖσ ὑψίστοις εὺλογημένος (King, Handbook of Engraved Gems, p. 377).

161:263 A large number of these may be seen in Archæologia, vol. xix.; and in the Proceedings of the Somerset Arch. and Nat. Hist. Society, vol. i. 1849.

161:264 Dennis, Cities of Etruria, vol. ii. p. 441.

162:265 Dennis, op. cit. vol. i. p. 199.

163:266 The writer knew the lamp well, and possessed the print here copied many years before reading Mr. Dennis's description.

164:267 Dennis, op. cit. vol. ii. p. 439.

164:268 None of the early Medusas are given by Montfaucon, whose "Antiquity" does not seem to include anything but quite late objects.

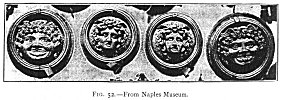

164:269 The accompanying heads, Fig. 52, from the Naples Museum, are simply door-knockers from Pompeii, but they admirably represent the transition period from the earlier grim and ferocious face, to the smiling and beautiful. It will be noted that the protruded tongue is retained in two, while in one there is an indication of the old splitting.

166:270 Dennis, op. cit. vol. ii. p. 22 1.

166:271 At Athens new-born infants "were commonly wrapped in a cloth, wherein was represented the Gorgon's head, because that was described in the shield of Minerva, the protectress of that city, whereby, it may be, infants were committed to the goddess's care" (Potter, Archæol. Græc. ii. p. 320).

167:272 The same objects appear over and over again in later times, avowedly as charms against the evil eye.

167:273 See gem, Fig. 18; also Water Bottle, Fig. 179, from the British Museum.

The dolphin is the badge of the well-known Somerset family of Fitz-James, two of whom, Richard, Bishop of London, and his nephew, Sir John Fitz-James, Lord Chief justice, were the two principal founders of Bruton School, A.D. 1519. The original foundation deed, a most interesting document, is given at length by the Rev. F. W. Weaver in Som. and Dor. Notes and Queries, iii. xxii. 241.

167:274 Plates in Dennis's Etruria, vol. ii. p. 387.

168:275 Coloured copies of these insignia will be found in Logan's History of the Scottish Gael.

168:276 "This valuable record," Mr. Hodgkin says (Italy and her Invaders A. D. 376 to 476. Oxford, 1880, Vol. i. p. 200) "was compiled in the fifth century. It is a complete Official Directory and Army List of the whole Roman Empire, and it is of incalculable value for the decision of all sorts of questions, antiquarian and historical." The work of Pancirolo consists of the original text, compiled as above, together with his lengthy and important Commentarium.

In the Bodleian Library is a very beautiful MS. copy (Canon. Misc. 378) of the text of the Notitia, and containing the whole of the insignia; moreover, all are highly coloured, so that the curious may learn precisely what these various badges were like. This is the more important because, even in those days, as the work fully explains, colour in itself entered largely as an element into the several designs.

169:277 It may be accepted as a fact that recognition of the sun was quite characteristic of the army of the East, while there are many more exceptions to the rule, in that of the West.

169:278 Surely it is no straining of Scripture to suggest that the Psalmist must p. 170 have been well used to the device as the central ornament, and familiar with its object, when he says: "For the Lord God is a sun and shield" (Psalm lxxxiv. 11).

171:279 "Ascarii Juniores, in luteo clypeo, quem latus limbus rubeus circumscribit, orbem aureum ferunt: unde octo luteæ cuspides acutæ exeunt. In Madruciatio, globus nigris lineis in septem partes dividitur, quæ forte septem terræ habitatæ climata referunt, eaque Imperio Rom. subesse."--Notitia, p. 39.

171:280 Many similar allusions to the colours of the various badges might be given, but in the Oxford MS. these all tell their own tale. It will be noticed that there was another legion--Ascarii Juniores--but these belonged to the Western Army and had a different shield.

172:281 The popular notion regarding coats of arms is no doubt accurately reflected by the leader-writer who penned the following: "Armorial bearings, we may presume, were originally adopted to distinguish a military leader in the throng of fighting men from a host of others similarly accoutred, and all with their vizors down. They served, in short, as a sort of hieroglyphics, invented in an unlettered age, before the capability of reading a more conventional form of writing had become general" (Standard, June 9, 1894). He will therefore perhaps be surprised to see how much like mediæval shields were those of the Roman legions.

175:282 The combination of protective symbols upon the same shield is by no means a feature peculiar to mediæval blazonry or modern heraldry. The ancient Etruscans were adepts at it, for on a coupe found at Vulci, now in the Berlin Museum (given in Daremberg et Saglio, p. 187), is a combat between Poseidon and Ephialtes. On the shield of the former are depicted a dolphin, scorpion, stag, serpent, lizard and crab, while on that of the latter there is only a horse rampant (the modern arms of Kent) with the legend KALON.

177:283 "Fans of Japan," M. Salwey in Spectator, Mar. 17, 1894.