A QUARTERLY MAGAZINE

A CHINESE ANTI-MACHIAVELLI.

SHORTLY before Frederick the Great ascended the throne, he wrote a criticism of Machiavelli's doctrines of statecraft, which in those times were considered the sum-total of political wisdom, in a treatise entitled Anti-Machiavelli. Machiavelli, an Italian statesman, educated in the school of Italian politics with its intrigues and coups d'état, advised princes to maintain their sovereignty by crooked means, by treachery, and violence, but the young Crown Prince of Prussia condemned the book not only as immoral but also as very unwise,—in a word, as absolutely wrong; and he stated his own views that a prince could maintain himself best by serving the people with ability and honesty. "Government is needed," the young Frederick argued, "and so long as a prince will do his duty, his people will need him and will be grateful for the service he gives." In contrast to the notion of Louis XIV. of France, who said; "L'état c'est moi," Frederick's maxim was that a king is, and should consider himself, "the first servant of his people." The statesmen of Europe smiled at the ingenuity of the fantastic idealist, as which they regarded him, but Frederick proved to them by deeds that his maxims were superior to the intricate wiles of the old diplomacy.

It is interesting to learn that in China too there lived a sovereign who came to the conclusion that honesty is the best policy, and whose main maxim of government may be summed up in the principle, to serve the interests of the people. The man of whom p. 734 we speak is K'ang-Hi, and the famous document which expresses his views on the subject is called the "Holy Edict."

THE HOLY EDICT OF K'ANG-HI.

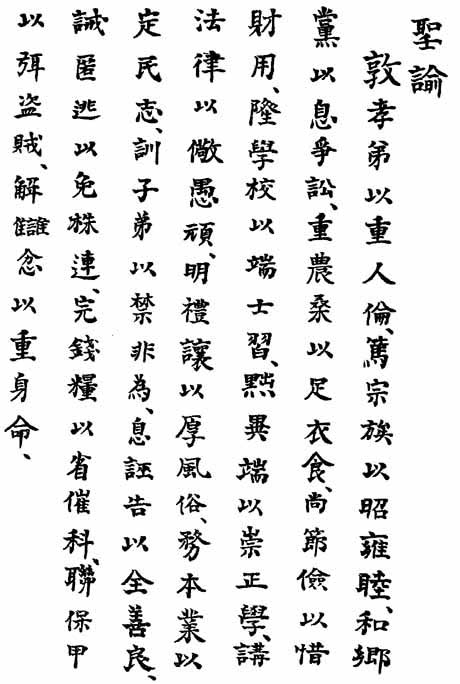

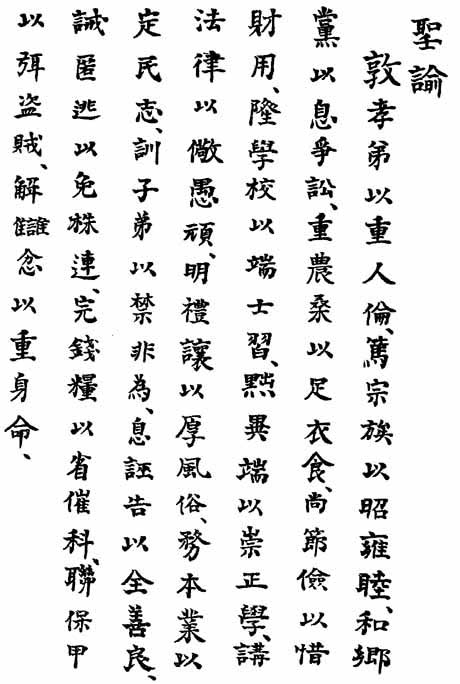

K'ang-Hi ###, the second emperor of the present dynasty called Ch'ing, was distinguished not only in the field as a successful general, but also as a good ruler by the wisdom of his government. He published in the latter part of his glorious reign an advice to government officials in sixteen maxims, known under the name Shêng Yü ###, i.e., "Holy Edict." They were written on slips of wood and hung up in all the imperial offices of the country.

Yung-Ching, the son and successor of K'ang-Hi, republished his father's edict with a preface and amplifications of his own. He says in the preface:

"Our sacred father, the benevolent emperor, for a long period taught the method of a perfect reform. His virtue was as wide as the ocean, and his mercy extended to the boundaries of heaven. His benevolence sustained the world, and his righteousness guided the teeming multitudes of his people. For sixty years, in the morning and in the evening, even while eating and dressing, his sole care was to rouse all, both his own subjects and those living outside his domain, to exalt virtue, to rival with each other in liberal-mindedness and in keeping engagements with fidelity. His aim was that all should cherish the spirit of kindness and meekness, and that they should enjoy a reign of eternal peace.

"With this purpose in view, he graciously published an edict consisting of sixteen maxims, wherein he informed the soldiers of the Tartar race (at the capital), and also the soldiers and people of the various provinces, of their whole duty concerning the practice of the essential virtues, the duties of husbandry and the culture of cotton and silk, labor and rest, common things and ideal aspirations, public and private affairs, great things and small, and whatever was proper for the people to do; all this he elucidated thoughtfully. He looked upon his people as his own children. His sacred p. 735 instructions are like the sayings of the ancient sages, for they point out the right way of assured safety.

"Ten thousand generations should practise his maxims. To improve them is impossible.

"Since we succeeded to the charge of this great empire and are ruling now over the millions of people, we have conformed our mind to the mind of our sacred father and our government to his, morning and evening, and with untiring1 energy, we endeavor to conform to the ancient traditions and customs. . . .

"With great reverence, we publish the sixteen maxims of the Sacred Edict on the principles of which we have deeply meditated. We have amplified them by an addition of ten thousand characters, explaining them with similes from things far and near, quoting ancient books in order to fully explain their meaning."

The preface is signed "Yung Ching," bearing the date of the second year of his rule, the second day of the second month. His seal consists of two impressions: one shows the characters "Attend to the people," the other "Venerate heaven."

My source of the Chinese text is a manuscript copy, written by an unknown Sinologist as marginal notes in an old translation of the Sacred Edict by the Rev. Willliam Milne, Protestant Missionary at Malacca, printed in 1817 at London for Black, Kingsbury & Allen, Booksellers for the Hon. East India Co. The handwriting of the Chinese characters is awkward but clear, obviously made with a Western pen, not a native's brush. It contains two mistakes, which were corrected by Mr. Teitaro Suzuki, who also assisted me in the translation.

The copy here reproduced has been written by Mr. Kentok Hori of San Francisco, California, well known among his countrymen for his elegant penmanship.

TEXT OF THE SIXTEEN MAXIMS.1

TRANSLATION OF THE HOLY EDICT.

Cultivate filial piety and brotherly love, for thereby will be honored social morality.

MAXIM II.

Render family relations1 cordial, for thereby appears the bliss of harmony.

Let concord prevail among neighbors,2 for thereby you prevent quarrels and law suits.

Honor husbandry and silk industry, for thereby is supplied raiment and food.

MAXIM V.

Esteem thrift and economy,3 for thereby is saved money in business.

Promote academic institutions, for thereby are established scholarly habits.

Do away with heretical systems, for thereby is exalted the orthodox doctrine.

Explain laws and ordinances,4 for thereby are warned the foolish and obstinate.

MAXIM IX.

Recommend polite manners, for thereby is refined the social atmosphere.1

MAXIM X.

Develop legitimate business, for thereby the people's desire is rendered pacific.

MAXIM XI.

Instruct the youth,2 for thus you prevent crime.

Suppress false denunciations, for thereby you protect the good and the worthy.3

MAXIM XIII.

Warn those who conceal deserters, for thereby they escape being entangled in their fate.4

Enforce the payment5 of taxes,6 for thereby you avoid the imposition of fines.

MAXIM XV.

Keep disciplined the police forces,7 for thereby are prevented thefts and robberies.

Settle enmities and dissensions, for thereby you protect human lives.8

Each maxim of the Holy Edict consists of seven characters, and exhibits the same grammatical construction. The first three characters express the advice given; the fourth character is uniformly the same word, i which means "thereby," "thus," or "so that": the concluding three characters contain the result to be obtained.

The style of the Holy Edict will naturally appear pedantical to a Western reader, but if we consider its contents and the spirit in which it is written, we must grant that it is a remarkable document which reveals to us the inmost thought of a great Chinese ruler.

YUNG CHING'S AMPLIFICATIONS.

Yung Ching, the son of K'ang-Hi and his successor, adds to the sixteen Maxims of his father his amplifications, as he styles them, which may be characterised as sermons on the bliss of virtue and the curse of evil-doing.

Yung Ching's comments on the first Maxim are typical Chinese expositions of the significance of ### hsiao, i.e., "filial piety," the cardinal virtue of Confucian ethics. It reads as follows:

"Filial piety is the unalterable statute of heaven, the corresponding operations of earth, and the common obligations of all people. Have those who are void of filial piety never reflected on the natural affection of parents to their children?

"Before leaving the parental bosom, if hungry, you could not feed yourselves; if cold, you could not put on clothes. Parents judge by the voice and anxiously watch the features of their children; their smiles create joy, their weeping, grief. On beginning to walk they leave not their steps; when sick, they do not sleep or eat; thus they nourish and teach them. When they come to years they give them wives, and settle them in business, exhausting their minds by planning and their strength by labor. Parental virtue is truly great and exhaustless as that of heaven.

"The son of man that would recompense one in ten thousand of favors of his parents, should at home exhaust his whole heart, abroad exert his whole strength. Watch over his person, practise economy, diligently labor for, and dutifully nourish them. Let him not gamble, drink, quarrel, or privately hoard up riches for his own sake! Though his external manners may not be perfect, yet there should be abundant sincerity!

"Let us enlarge a little here by quoting what Tsang-Tsze says: 'To move unbecomingly is unfilial; to serve the prince without fidelity is unfilial; to act disrespectful as a mandarin is unfilial; to be insincere to a friend is unfilial; to be cowardly in battle is also unfilial.' These things are comprehended in the duty of an obedient son.

"Again, the father's elder son is styled viceroy of the family; and the younger brothers [after the father's death] give him honorable appellation of family superior.

"Daily, in going out and coming in, whether in small or great affairs, the younger branches of his family must ask his permission. In eating and drinking, they must give him the preference; in conversation, yield to him; in walking, keep a little behind him; in sitting and standing, take the lower place. These are illustrative of the duties of the younger brothers.

"If I meet a stranger, ten years older than myself, I would treat him as an eIder brother; if one five years older, I would walk with my shoulder a little behind his; how much more then ought I to act thus towards him who is of the same blood with myself!

"Therefore, undutifulness to parents and unbrotherly conduct are intimately connected. To serve parents and elder brothers are things equally important.

"The dutiful child will also be the affectionate brother; the dutiful child and affectionate brother will, in the country, be a worthy member of the community; in the camp, a faithful and bold soldier. You, soldiers and people, know that children should act filially and brothers fraternally; but we are anxious lest the thing, becoming to you all, should not be borne in mind, and you thus trespass the bounds of the human relations."

In his amplification of the third Maxim, Yung Ching quotes a saying of his father, which reads:

"By concord, litigation may be nipped in the bud."

Yung Ching's further comments on Maxim III are a sermon on concord:

"It is evident that a man should receive all, both relatives and indifferent persons, with mildness; and manage all, whether great or small affairs, with humility. Let him not presume on his riches, and despise the poor; not pride himself of his illustrious birth, and contemn the ignoble; not arrogate wisdom to himself and impose on the simple; not rely on his own courage and shame the weak; but let him, by suitable words, compose differences; kindly excuse people's errors; and, though wrongfully offended, settle the matter according to reason. . . . .

"Let the aged and the young in the village be united as one body, and their joys and sorrows viewed as those of one family. When the husbandman and the merchant mutually lend, and when the mechanic and the shopman mutually yield, then the people will harmonise with the people. . . . . When the the soldiers exert their strength to protect the people, let the people nourish that strength. When the people spend their money to support the soldiers, let the soldiers be sparing of that money; thus both soldiers and people will harmonise together. . . . .

"The whole empire is an aggregate of villages; hence you ought truly to conform yourselves to the sublime instructions of our sacred father and honor the excellent spirit of concord: then, indeed, filial and fraternal duties would be more attended to, kindred more respected, the virtue of villages become more illustrious, approximating habitations prosper, litigations cease, and man enjoy repose through the age of ages! The union of peace will extend to myriads of countries, and superabounding harmony diffuse itself through the universe!"

Concerning the fourth Maxim, Yung Ching writes:

"Of old time the emperors themselves ploughed, and their empresses cultivated the mulberry tree. Though supremely honorable, they disdained not to labor, in order that, by their example, they might excite the millions of the people to lay due stress on the essential principles of political economy."

Learning is perhaps more highly honored in China than in any other country. Yung Ching amplifies the sixth Maxim in a sermon on the duties of a scholar:

"The scholar is the head of the four classes of people. The respect that others show to him should teach him to respect himself, and not degrade his character. When the scholar's practice is correct, the neighborhood will consider him as a model of manners. Let him, therefore, make filial and fraternal duties the beginning and talent the end; place enlarged knowledge first and literary ornaments last. Let the books he reads be all orthodox, and the companions he chooses all men of approved character. Let him adhere rigorously to propriety, and watchfully preserve decency, lest he ruin himself, and disgrace the walls of his college, and lest that, after having become famous, the shadows of conscious guilt and shame should haunt him under the bed cover.

"He who can act according to this maxim is a true scholar.

"But there are some who keenly contend for fame and gain, act contrary to their instructions, learn strange doctrines and crooked sciences, p. 742 not knowing the exalted doctrine. Giving wild liberty to their words, they talk bigly, but effect nothing. Ask them for words, and they have them; search for the reality, and they are void of it. . . . .

"With respect to you, soldiers and people, it is to be feared that you are not aware of the importance of education, and suppose that it is of no consequence to you. But though not trained up in the schools, your nature is adapted to the common relations. Mung-Tsze said: 'Carefully attend to the instructions of the schools—repeatedly inculcate filial and fraternal duties.' He also said: 'When the common relations are fully understood by superiors, affection and kindness will be displayed among inferiors.' Then it is evident that the schools were not intended for the learned only, but for the instruction of the people also."

As to the seventh Maxim, we find what may be considered as a suppression of religious liberty in China, and such it is in a certain way and with certain limitations.

Professor De Groot has devoted an elaborate essay1 on the subject which we have reviewed in The Monist for January, 1904. The present edict truly expresses the spirit of the Chinese government in matters of religion. The great emperor K'ang-Hi is anxious to establish the orthodox religion of China which is practically Confucianism, but he tolerates Taoism and Buddhism. His son, Emperor Yung Ching, amplifies his father's maxim by saying that it discriminates only against the corruptors of the doctrines of Confucius, Lao-Tze, and Buddha, and also condemns secret fraternities, such as exist all over China and become easily centers of sedition, as we have seen in the Boxer movement which has recently originated.

[As a rule religions are tolerated until they come in conflict with the basic principle of Confucianism, which is expressed in that one syllable hsiao, i.e., "filial piety." There are millions of Muhammedans in China who are practically unmolested in their faith. The Muhammedan rebellion in 1865 was a purely political affair and had nothing to do with religion. Further the Jews lived in China undisturbed for many centuries; they could build synagogues and worship God in their own way without any interference from the government. The fact is that both Muhammedans and Jews complied with the main request of Confucianism and inculcated reverence for parents and a recognition of the emperor's authority. The Nestorians met with a hearty welcome from the government and flourished for some time. Marco Polo tells us how much Kublai Khan was interested in Christianity, and that he wrote a letter to the Pope which, however, was never delivered, requesting him to send missionaries to China. The great K'ang-Hi, the author of the Holy Edict, favored the Jesuits and not only allowed them to preach Christianity, but did not hesitate to entrust them with high and important government positions. The animosity against Christianity is of recent date and is mainly based upon the notion that native Christians must despise the sages of yore, that they must repudiate their family (which is frequently demanded by missionaries on account of the ritual of ancestor worship), and that they place the authority of Christ (which practically means the church) above the authority of their parents, as indicated in the passage (Luke xiv. 26) where Christ says: "If any man come to me and hate not his father, and mother, and wife, and children, and brethren, and sisters, yea, and his own life also, he cannot be my disciple." The very words "to hate father and mother," whatever the interpretation may be, jars on the ear of the Chinese. This verse in combination with denunciations of missionaries who call Buddha "the night of Asia," Confucius "a blind leader of the blind," etc., has done much harm to Christianity.]

Yung Ching says:

"From of old three sects have been delivered down. Beside the sect of the learned, there are those of Tao and Fŭh. Chu-Tsze says: 'The sect of Fŭh regard not heaven, earth, or the four quarters, but attend only to the heart; the sect of Lao exclusively to the preservation of the animal spirits.' This definition of Chu-Tsze is correct and impartial and shows what Fŭh and Tao originally aimed at.

"Afterwards, however, there arose a class of wanderers, who, void of any source of dependence, stole the names of these sects, but corrupted their principles.

"And what is still worse, lascivious and villainous persons creep in secretly among them; form brotherhoods, bind themselves to each other by oath, meet in the night and disperse at the dawn, violate the laws, corrupt the age, and impose on the people,—and behold! one morning the whole business comes to light. They are seized according to law, their innocent neighbors injured—their own families involved—and the chief of their cabal punished with extreme rigor. What they vainly thought would prove the source of their felicity becomes the cause of their misery. . .

"By his benevolence, our sacred father, the benevolent Emperor, refined the people; by his rectitude he polished them; by his most exalted talents he set forth in order the common relations and radical virtues. His sublime and luminous instructions form the plan by which to rectify the hearts of the men of the age. A plan the most profound and excellent! . . . .

"The injury of torrents, flames, robbers, and thieves, terminates on the body; but that of false religions extends to the human heart. Man's heart is originally upright and without corruption; and, were there firm resolution, p. 744 men would not be seduced. A character, square and upright, would appear. All that is corrupt would not be able to overcome that which is pure. In the family there would be concord; and, on meeting with difficulties, they would be converted into felicities.

"He who dutifully serves his father and faithfully performs the commands of his prince, completes the whole duty of man, and collects celestial favor. He who seeks not a happiness beyond his own sphere and rises not up to evil, but attends diligently to the duties proper for him, will receive prosperity from the gods.

"Attend to your agriculture and to your tactics. Be satisfied in the pursuit of the cloth and the grain, which are the common necessaries. Obey this true, equitable, and undeviating doctrine. Then false religions will not wait to be driven away: they will retire of their own accord."

Concerning the knowledge of laws, Yung Ching says:

"Though the law has a thousand chapters and ten thousand sections, yet it may be summed up in this sentence: 'It agrees with common sense, and its norm is reason.' Heavenly reason and man's common sense can be understood by all. When the heart is directed by common sense and by reason, the body will never be subject to punishment."

In the amplification to Maxim XII we find the following exhortation:

"The commandment is exalted and most perspicuous, yet there are some who dare presume to transgress. The lust of gain having corrupted their hearts, and their nature being moulded by deceit, they spurt out the poison lodged within, vainly hoping that the law will excuse them. But they consider not that, if a false statement be once discovered, it can by no means pass with impunity. To move to litigations with the view of entrapping others, is the same as to dig a pit into which they themselves shall fall."

Yung Ching's sermon on the fourteenth Maxim on taxes shows that the Chinese officials had sometimes great trouble in collecting the taxes. He says:

"Since our dynasty established its rule, the proportions of the revenue have been fixed by a universally approved statute; and all the other unjust items have been completely cancelled: a thread or a hair too much is not demanded from the people.

"In the days of our sacred father, the benevolent Emperor, his abounding benevolence and liberal favor fed this people for upwards of sixty years. Thinking daily how to promote the abundance and happiness of the people, he greatly diminished the revenue. . . . .

"Pay in all the terms and wait not to be urged. Then you may take what is over and nourish your parents, complete the marriage ceremonies of your sons and daughters, satisfy your own morning and evening wants, and prepare for the annual feasts and sacrifices. The district officers may then sleep at ease in their public halls. The villages will no more be teased in the night by the calls of the tax-gatherers. Above you or below you none will be evolved. Your wives and children will be easy and at rest. There is no joy greater than this.

"If you be not aware of the importance of the revenue to the government, and that the law cannot dispense with it, perhaps you will positively refuse or deliberately put off the payment. The mandarins, being obliged to balance their accounts, and give in their reports at the stated times, must be rigorously severe.

"The collectors will have to apply the whip, cannot avoid pressing their demands for money on you. Knocking on your doors, like hungry hawks, they will devise numerous methods of getting a supply of their wants. These nameless ways of spending will probably amount to more than the sum which ought to have been paid; and after all, the tax cannot be dispensed with.

"We know not what benefit can accrue from this. Rather than to give presents to satisfy the rapacity of the police officers, how much better would it be to clear off the just demands of the nation! Rather than prove yourselves to be obstinate, refusing the payment of the revenue, would it not be better to keep the law as a peace-abiding people? Every one, even the most stupid, knows this. . . . .

"Try to think that the daily and nightly vexations and labors of the palace are all in the service of the people. When there is an inundation, dykes must be raised to keep it off. When the demon of drought appears, prayer must be offered for rain; when there are locusts, they must be destroyed. If fortunately the calamity be averted, you all enjoy the profits. When unfortunately it comes, your taxes are remitted and alms liberally dealt out to you.

"If it be thus, and the people still can suffer thernselves to evade the payment of taxes, and hinder the supply of the wants of the govemment, ask yourselves how it is possible for you to be at ease? This may be compared to the conduct of an undutiful son: while with his parents he receives his share of the property, and ought afterwards to nourish them, and thus discharge his duty; the parents also manifest the utmost affection, diligence, and anxiety, and leave none of their strength unexerted; yet the son appropriates their money to his own private use; diminishes their savory food; and feeds them with reluctant and obstinate looks. Can such a person be called a child of a human being?

"We use these repeated admonitions, solely wishing you, soldiers and people, to think of the army and the nation above you; and of your persons and families below you. Then abroad you will have the fame of having faithfully exerted your ability, and at home, peacefully enjoy the fruits of it. The mandarins will neither trouble you, nor the clerks vex you—what joy equal to this!"

The sixteenth Maxim is practically a sermon on anger. Yung Ching says:

"Our sacred father, the benevolent Emperor, in consequence of desiring to manifest regard to you, closed the sixteen maxims of the admonitory Edict by teaching to respect life. The heart of heaven and earth delights in animated nature; but fools regard not themselves. The government of a good prince loves to nourish, but multitudes of the ignorant lightly value life. If the misery rise not from former animosities, it proceeds from momentary anger. The violent, depending on the strength of their backbone, kill others, and throw away their own lives. . . . .

"Cherish mildness, disperse passion; then you need not wait for the mediation of others: habits of contention will cease of their own accord. How excellent would such manners be!

"Kung-Tsze said, 'When anger rises, think of the consequences.' Mung-Tsze said, 'He that repeatedly treats one rudely is a fool.' The doctrines delivered down by these sages, from more than a thousand years ago, correspond exactly with those explained in the Edict by our sacred father, the benevolent Emperor.

"Soldiers and people, respectfully obey this: disregard it not. Then the people in their cottages will be protected; the soldiers in the camp enjoy repose; below you will support your family character, and above reward the nation. Comfortable and easy in days of abundance, all will advance to a virtuous old age. Does not this illustrate the advantages of settling animosities?"

EDITOR.

1. The larva of the mosquito is an animalcule which is constantly wriggling in the water. It has a name of its own in Chinese, being called Chieh-Chieh, which serves as a well-known symbol of an indefatigable activity. For the sake of simplicity, we have simp1y translated it "untiring."

1. The text of the Holy Edict has been incorporated in an edition of the T'ai Shang Kan Ying P'ien, published by the Association of the Middle Flower, a Chinese society at Yokohama. The text agrees wlth the present one with the exception of two cases, viz., Maxim II, word 7, and Maxim XIII, word 2, which are replaced by homonyms, and in Maxim XII the order of the characters 6 and 7 is inverted. Our translation is as literal as possible.

1. Literally: "Make cordial ||relatives|| [and] kin."—Here as well as elsewhere, two synonyms are used to express one idea. They had perhaps been better translated by one word.

2. Literally: "Harmonise ||the village's|| inhabitants."

3. See note to Maxim II.

4. See note to Maxim II.

1. Literally: "Wind and habits"; ### Feng = "wind," means also "climate," and "atmosphere." Both characters together are best translated "social atmosphere."

2. Literally: "Boys and youngsters." See note to Maxim II.

3. See note to Maxim II.

4. Literally: "Escape bush entanglement," which means "being entangled in the (same) bush," i.e., "being caught with criminals."

5. Literally: "Complete," which means "be punctual in collecting."

6. The term "taxes" means in Chinese "cash payments and food products," because the tax payers have their choice to pay either in coin or in produce.

7. Literally: "Protecting armies."

8. Literally: "Persons and their destinies."

1. Sectarianism and Religious Persecution in China. Amsterdam: Johannes Müller.