Evolution of the Dragon, by G. Elliot Smith, [1919], at sacred-texts.com

Evolution of the Dragon, by G. Elliot Smith, [1919], at sacred-texts.com

Aphrodite was associated not only with the cowry, the pearl, and the mandrake, but also with the octopus, the argonaut, and other cephalopods. Tümpel seems to imagine that the identification of the goddess with the argonaut and the octopus necessarily excludes her association with molluscs; and Dr. Rendel Harris attributes an equally exclusive importance to the mandrake. But in such methods of argument due recognition is not given to the outstanding fact in the history of primitive beliefs. The early philosophers built up their great generalizations in the same way as their modern successors. They were searching for some explanation of, or a working hypothesis to include, most diverse natural phenomena within a concise scheme. The very essence of such attempts was the institution of a series of homologies and fancied analogies between dissimilar objects. Aphrodite was at one and the same time the personification of the cowry, the conch shell, the purple shell, the pearl, the lotus, and the lily, the mandrake and the bryony, the incense tree and the cedar, the octopus and the argonaut, the pig, and the cow.

Every one of these identifications is the result of a long and chequered history, in which fancied resemblances and confusion of meaning play a very large part. But I cannot too strongly repudiate the claim made by Sir James Frazer that such events are merely so

many evidences of the innate human tendency to personify nature. The history of the arbitrary circumstances that were responsible for the development of each one of these homologies is entirely fatal to this wholly unwarranted speculation. 1 Tümpel claims 2 the Aphrodite was associated more especially with "a species of Sepia". He refers to the attempts to associate the goddess of love with amulets of univalvular shells "in virtue of a certain peculiar and obscene symbolism". 3 Naturalists, however, designate with the term Venus Cytherea certain gaping bivalve molluscs.

But, according to Tümpel (p. 386), neither univalvular nor bivalve shells can be regarded as a real part of the goddess's cultural equipment. There is no representation of Aphrodite coming in a shell from across the sea. 4 The truly sacred Aphrodite-shell was entirely different, so Tümpel believes: it was obviously difficult to preserve, but for that reason more worthy of notice, for the small χοιρίναι, (pectines), virginalia marina (Apuleius de mag. 34, 35, and in reference thereto, Isidor. origg. 9, 5, 24) or spuria (σπόρια) were only the commoner and more readily obtained surrogates: the univalvular shells

(μονοθυρα of Aristotle), such as those just mentioned, and the other ὄστρεα of Aphrodite, the Nerites (periwinkles, etc.), the purple shell and the Echineïs were also real Veneriae conchae. Among the Nerites Aelian enumerates (N.A. 14, 28): Ἀφροδίτην δὲ συνδιαιτωμένην έν τῂ θαλάττη ἡσθὴναί τε τῷ Νηρίτῃ τῷδε καὶ ἔχειν ἀυτὸν φίλον. On account of their supposed medicinal value in cases of abortion and especially as a prophylactic for pregnant women the Ἐχενηΐς (pure Latin re[mi]mora) was called ὠδινολὐτη 1 (Pliny, 32, 1, 5: pisciculus!). According to Mutianus (Pliny, 9, 25 (41), 79 f.), it was a species of purple shell, but larger than the true Murex purpura. From this the sanctity of the Echineïs to the Cnidian Aphrodite is demonstrated: "quibus (conchis) inhaerentibus plenam ventis stetisse navem portantem Periandro, ut castrarentur nobilis pueros, conchasque, quae id praestiterint, apud Cnidiorum Venerem coli" (Pliny).

Tümpel then (p. 387) accuses Stephani of being mistaken in his interpretation of Martial's Cytheriacae (Epign. II, 47, 1 = purple shells) as the amulets of Aphrodite, and claims that Jahn has given the correct solution of the following passages from Pliny (N.H., 9, 33 [52], 103, compare 32, 11 [53]): "navigant ex his (conchis) veneriae, praebentesque concavam sui partem et aurae opponentes per summa aequorum velificant"; and further (9, 30 [49], 94): "in Propontide concham esse acatii modo carinatam inflexa puppe, prora rostrata, in hac condi nauplium animal saepiae simile ludendi societate sola. duobus hoc fieri generibus: tranquillum enim vectorem demissis palmulis ferire ut remis; si vero flatus invitet, easdem in usu gubernaculi porrigi pandique buccarum sinus aurae".

Tümpel claims (pp. 387 and 388) that this quotation settles the question. Aphrodite's "shell," according to him, is the Nauplius (depicted as a shell-fish, with its sail-like palmulæ spread out to the wind, but with the same sails flattened into plate-like arms for steering), clearly "a species of Sepia," wholly like Aphrodite herself, a ship-like shell-fish sailing over the surface of the water, the concha veneria. [The analogy to a ship bearing the Great Mother is extremely ancient and originally referred to the crescent moon carrying the moon-goddess across the heavenly ocean.]

Elsewhere (p. 399) he discusses the reasons for the connexion of Aphrodite with the "nautilus," by which is meant the argonaut of zoologists.

But if Jahn and Tümpel have thus clearly established the proof of the intimate association of Aphrodite with certain cephalopods, they are wholly unjustified in the assumption that their quotations from relatively modern authors disprove the reality of the equally close (though more ancient) relationship of the goddess to the cowry, the pearl-shell, the trumpet-shell, and the purple-shell.

It must not be forgotten that, as we have already seen, the primitive shell-cults of the Erythræan Sea had been diffused throughout the Mediterranean area long before Aphrodite was born upon the shores of the Levant, and possibly before Hathor came into existence in the south. The use of the cowry and gold models of the cowry goes back to an early time in Ægean history. 1 And the influence of Aphrodite's early associations had become blurred and confused by the development of new links with other shells and their surrogates.

But the connexion of Aphrodite with the octopus and its kindred played a very obtrusive part in Minoan and Mycenæan art; and its influence was spread abroad as far as Western Europe 2 and towards the East as far as America. In many ways it was a factor in the development of such artistic designs as the spiral and the volute, and not improbably also of the swastika.

Starting from the researches of Tümpel, a distinguished French zoologist, Dr. Frédéric Houssay, 3 sought to demonstrate that the cult of Aphrodite was "based upon a pre-existing zoological philosophy". The argument in support of his claim that Aphrodite was a personification of the octopus must be sharply differentiated into two parts: first, the reality of the association of the octopus with the goddess, of which there can be no doubt; and secondly, his explanation of it, which (however popular it may be with classical writers and modern scholars) 4 is not only a gratuitous assumption, but also, even if it were

Click to enlarge

Fig. 22

Fig. 22.—(a) Sepia Officinalis, after Tryon, "Cephalopoda".

(b) Loligo Vulgaris, after Tryon.

(c) The position usually adopted by the resting Octopus, after Tryon.

based upon more valid evidence than the speculations of such recent writers as Pliny, would not really carry the explanation very far.

I refer to his claim that "les premiers conquérants de la mer furent induits en vénération du poulpe nageur (octopus) parce qu’ils crurent que quelque-uns de ces céphalopodes, les poulpes sacrés (argonauta) avaient, comme eux et avant eux, inventé la navigation" (op. cit., p. 15). Idle fancies of this sort do not help us to understand the arbitrary beliefs concerning the magical powers of the octopus.

The real problem we have to solve is to discover why, among all the multitude of bizarre creatures to be found in the Mediterranean Sea, the octopus and its allies should thus have been singled out for distinctive appreciation, and also acquired the same remarkable attributes as the cowry.

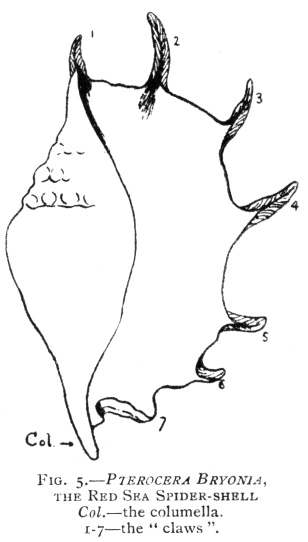

I believe that the Red Sea "Spider shell," Pterocera, 1 was the link between the cowry and the octopus. This shell was used, like the cowry, for funerary purposes in Egypt and as a trumpet in India. 2 But it was also depicted upon a series of remarkable primitive statues of the god Min, which were found at Coptos during the winter 1893-4 by Professor Flinders Petrie. 3 Some of these objects are now in the Cairo Museum and the others in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. They are supposed to be late predynastic representations of the god Min. If this supposition is correct they are the earliest idols (apart from mere amulets) that have been preserved from antiquity.

Upon these statues, representations of the Red Sea shell Pterocera bryonia are sculptured in low relief. Mr. F. Ll. Griffith is disinclined to accept my suggestion that the object of these pictures of the shell was to animate the statues. But whether this was their purpose or not, it is probably not without some significance that these life-giving shells were associated with so obtrusively phallic a deity as Min. In any case they afford concrete evidence of cultural contact between Coptos and the Red Sea, and indicate that these particular shells were chosen as symbols of that sea or its coast.

The distinctive feature of the Pterocera is that the mantle in the adult expands into a series of long finger-like processes each of which

secretes a calcareous process or "claw". There are seven 1 of these claws as well as the long columella (Fig. 5). Hence, when the shell-cults were diffused from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean (where the Pterocera is not found), it is quite likely that the people of the Levant may have confused with the octopus some sailor's account of the eight-rayed shell (or perhaps representations of it on some

|

I have already mentioned that the mandrake is believed to possess the same magical powers. Sir James Frazer has called attention to the fact that in Armenia the bryony (Bryonia alba) is a surrogate of the mandrake and is credited with the same attributes? Lovell Reeve ("Conchologia Iconica," VI, 1851) refers to the Red Sea Pterocera as the "Wild Vine Root" species, previously known as Strombus radix brioniae; and Chemnitz ("Conch. Cab.," 1788, Vol. X, p. 227) says the French call it "Racine de brione femelle imparfaite," and refer to it as "the maiden". Here then is further evidence that this shell (a) was associated in some way with a surrogate of the mandrake (Aphrodite), and (b) was regarded as a maiden. Thus clearly it has a place in the chequered history of Aphrodite. I have suggested the possibility of its confusion with the octopus, which may have led to the inclusion of the latter within the scope of the marine creatures in Aphrodite's cultural equipment. According to Matthioli (Lib. 2, p. 135),

another of Aphrodite's creatures, the purple shell-fish, was also known as "the maiden". By Pliny it is called Pelogia, in Greek πορφυρα; and πορφυρώματα was the term applied to the flesh of swine that had been sacrificed to Ceres and Proserpine (Hesych.). In fact, the purple-shell was "the maiden" and also "the sow": in other words it was Aphrodite. The use of the term "maiden" for the Pterocera suggests a similar identification. To complete this web of proof it may be noted that an old writer has called the mandrake the plant of Circe, the sorceress who turned men into swine by a magic draught. 1 Thus we have a series of shells, plants, and marine creatures accredited with identical magical properties, and each of them known in popular tradition as "the maiden". They are all culturally associated with Aphrodite.

I shall have occasion (infra, p. 177) to refer to M. Siret's account of the discovery of the Ægean octopus-motif upon Æneolithic objects in Spain, and of the widespread use in Western Europe of certain conventional designs derived from the octopus. M. Siret also (see the table, Fig. 6, on p. 34 of his book) makes the remarkable claim that the conventional form of the Egyptian Bes, which, according to Quibell, 2 is the god whose function it is to preside over sexual intercourse in its purely physical aspect, is derived from the octopus. If this is true—and I am bound to admit that it is far from being proved—it suggests that the Red Sea littoral may have been the place of origin of the cultural use of the octopus and an association with Hathor, for Bes and Hathor are said to have been introduced into Egypt from there. 3

That the octopus was actually identified with the Great Mother and also with the dragon is revealed by the fact of the latter assuming an octopus-form in Eastern Asia and Oceania, and by the occurrence of octopus-motifs in the representation of the goddess in America. One of the most remarkable series of pictures depicting the Great Mother is found sculptured in low relief upon a number of stone slabs from Manabi in Central America, 4 one of which I reproduce here

[paragraph continues] (Fig. 21b). The head of the goddess is a conventionalized octopus; to that was added a body consisting of a Loligo; and, to give greater definiteness to this remarkable process of building up the form of the goddess, conventional representations of her arms and legs (and in some of the sculptures also the pudendum muliebre) were added. Thus there can be no doubt of the identification of this American Aphrodite and the octopus.

In the Polynesian Rata-myth there is a very instructive series of manifestations of the dragon. 1 The first form assumed by the monster in this story was a gaping shell-fish of enormous size; then it appeared as a mighty octopus; and lastly, as a whale, into whose jaws the hero Nganaoa sprang, as his representatives are said to have done elsewhere throughout the world (Frobenius, op. cit., pp. 59-219).

Houssay (op. cit. infra) calls attention to the fact that at times Astarte was shown carrying an octopus as her emblem, 2 and has suggested that it was mistaken for a hand, just as in America the thunderbolt of Chac was given a hand-like form in the Dresden Codex (vide supra, Fig. 13), and elsewhere (e.g. Fig. 12).

If this suggestion should prove to be well founded it would provide a more convincing explanation of the girdle of hands worn by the Indian goddess Kali 3 than that usually given. If the "hands" really represent surrogates of the cowry, the wearing of such a girdle brings the Indian goddess into line, not only with Astarte and Aphrodite, but also with the East African maidens who still wear the girdle of cowries. Kali's exploits were in many respects identical with those of the bloodthirsty Sekhet-manifestation of the Egyptian goddess Hathor. Just as Sekhet had to be restrained by Re for her excess of zeal in murdering his foes, so Siva had to intervene with Kali upon the battlefield

Click to enlarge

Fig. 23

Fig. 23.—A series of Mycenæan conventionalizations of the Argonaut and the Octopus (after Tümpel), which provided the basis for Houssay's theory of the origin of the triskele (a, c, and d) and swastika (b and e), and Siret's theory to explain the design of Bes's face (f and g).

flooded with gore (as also in the Egyptian story) to spare the remnant of his enemies. 1

166:1 Sir James Frazer, "Jacob and the Mandrakes," Proc. Brit. Academy.

166:2 K. Tümpel, "Die 'Muschel der Aphrodite,'" Philologus, Zeitschrift für das Classische Alterthum, Bd. 51, 1892, p. 385: compare also, with reference to the "Muschel der Aphrodite," O. Jahn, SB. d. k. Sächs. G. d. W., VII, 1853, p. 16 ff.; also IX, 1855, p. 80; and Stephani, Compte rendu pour l’an 1870-71, p. 17 ff.

166:3 See Jahn, op. cit., 1855, T. V, 6, and T. IV, 8: figures of the so-called Χοιρίναι, (from Χοῖρος in the double sense as "pig" and "the female pudendum"): Aristophanes, Eq. 1147; Vesp. 332; Pollux, 8, 16; Hesch. s.v.

166:4 The fact that no graphic representation of this event has been found is surely a wholly inadequate reason for refusing to credit the story. Very few episodes in the sacred history of the gods received concrete expression in pictures or sculptures until relatively late. A Hellenistic representation of the goddess emerging from a bivalve was found in Southern, Russia (Minns, "Scythians and Greeks," p. 345).

Tümpel cites the following statements: "te (Venus) ex concha natam esse autumant: cave tu harum conchas spernas!" Tibull. 3, 3, 24: "et faveas concha, Cypria, vecta tua"; Statius Silv. 1, 2, 117: Venus to Violentilla, "haec et caeruleïs mecum consurgere digna fluctibus et nostra potuit considere concha"; Fulgent. myth. 2, 4 "concha etiam marina pingitur (Venus) portari (I. HS:—am portare)"; Paulus Diacon. p. 52, "M. Cytherea Venus ab urbe Cythera, in quam primum devecta esse dicitur concha, cum in mari esset concepta cet".

167:1 From ὠδινο—"to have the pains of childbirth".

168:1 See Schliemann, "Ilios," p. 455; and Siret, op. cit.

168:2 Siret, op. cit. supra, p. 59.

168:3 "Les Théories de la Genèse à Mycènes et le sens zoologique de certains symboles du culte d’Aphrodite," Revue Archéologique, 3ie série, T. XXVI, 1895, p. 13.

168:4 It was adduced also by Tümpel and others before him.

169:1 or Pteroceras.

169:2 Jackson, op. cit., p. 38.

169:3 "Koptos," pp. 7-9, Pls. III. and IV.: for a discussion of the significance of these statues see Jean Capart, "Les Débuts de l’Art en Égypte," Brussels, 1904, p. 216 et seq.

170:1 This may help to explain the peculiar sanctity of the shell. Frazer, op. cit., 4.

171:1 Just as Hathor (or her surrogate Horus) turned men into the creatures of Set, i.e. pigs, crocodiles, et cetera.

171:2 "Excavations at Saqqara," 1905-1906, p. 14.

171:3 Maspero, "The Dawn of Civilization," p. 34.

171:4 Saville, "Antiquities of Manabi, Ecuador," 1907.

172:1 A detailed summary of the literature relating to the world-wide distribution of certain phases of the dragon-myth is given by Frobenius, "Das Zeitalter des Sonnesgottes," Berlin, 1904: on pp. 63-5 he gives the Rata-myth.

172:2 Which can also be compared with the conventional form of the thunderbolt.

172:3 Of course the hands had the additional significance as trophies of her murderous zeal. But I think this is a secondary rationalization of their meaning. An excellent photograph of a bronze statue (in the Calcutta Art Gallery), representing Kali with her girdle of hands, is given by Mr. Donald A. Mackenzie, "Indian Myth and Legend," p. xl.

173:1 F. T. Elworthy has summarized the extensive literature relating to hand-amulets ("The Evil Eye," 1895; and "Horns of Honour," 1900). Many of these hands have the definite reputation as fertility charms which one would expect if Houssay's hypothesis of their derivation from the octopus is well founded.