Fictitious and Symbolic Creatures in Art, by John Vinycomb, [1909], at sacred-texts.com

Fictitious and Symbolic Creatures in Art, by John Vinycomb, [1909], at sacred-texts.com

"Come not between the dragon and his wrath."

"King Lear," Act i. sc. 2.

The dragon does not seem to have been a native emblem with the Romans, and when they adopted it it was only as a sort of subordinate emblem—the eagle still holding the first place. It seems to have been in consequence of their intercourse with other nations either of Pelasgic or Teutonic race. Amongst all the new races which overran Europe at the termination of the classical period the dragon seems to have occupied nearly the same place that it held in the earlier stages of Greek life. Among the Teutonic tribes which settled in England the dragon was from the first a principal emblem, and the custom of

carrying the dragon in procession with great jollity on May eve to Burford is referred to by old historians. The custom is said by Brand also to have prevailed in Germany, and was probably common in other parts of England.

Nor was the dragon peculiar to the Teutonic races. Amongst the Celts it was the symbol of sovereignty, and as such was borne on the sovereign's crest. Mr. Tennyson's "Idylls" have made us familiar with the dragon of the great Pendragonship "blazing on Arthur's helmet as he rode forth to his last battle, and "making all the night a stream of fire." The fiery dragon or drake and the flying dragon of the air were national phenomena of which we have frequent accounts in old books.

The Irish drag means "fire," and the Welsh dreigiaw (silent flashes of lightning) "fiery meteors"; hence Shakespeare says:

A principal source of the Dragon legends in these countries is the Celtic use of the word "dragon" for "a chief." Hence Pen-dragon (sumus rex), a sort of dictator in times of danger. Those knights who slew a chief in battle slew a dragon, and the military title soon got confounded with the fabulous monster. The name or title Pendragon (dragon's head) was among British kings and princes what

[paragraph continues] Bretwalda was among the Saxons; and his authority or supremacy over the confederation was greater or less according to his valour, ability, and good fortune. Arthur succeeded his father Uther, and was raised to the pendragonship in the first quarter of the sixth century.

The dragon was a symbol among the heathen. One of the sons of Odin was thus invoked: "Child of the Dragon, Son of Conquest, arise! grasp thy silver spear; thy snowy steed prepare and haste thee to the strife of the shield! Uprise thou Dragon of Onslaught!" And again:

"The Dragon of the Shield struck his sounding war-board with his ponderous spada. The fierce-browed children of Hilda gathered round at the signal."

Maglocue, a British king who was a great warrior and of a remarkable stature, whose exploits had rendered him terrible to his foes, as a surname was called "The Dragon of the Isle," perhaps from his seat in Anglesey.

Cuthred, King of Wessex, bore a dragon on his banner. A dragon was also the device of the British King Uther Pendragon, or Dragon's-head, father or that King Arthur of chivalric memory, who so bravely withstood the incursions of the Saxons. Two

dragons addorsed—that is, back to back—are ascribed to Arthur, as well as several other devices.

Dragon's Hill, Berkshire, is where the legend says St. George killed the dragon. A bare place is shown on the hill where nothing will grow, and there the blood ran out. In Saxon annals we are told that Cedric, founder of the West Saxon kingdom, slew there Naud, the pendragon, with 5000 men. This

|

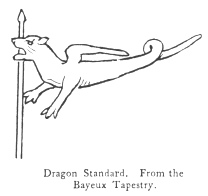

"It has sometimes been thought," says Miss Millington, "that the royal Saxon banner bore a dragon; certain it is, that on the Bayeux tapestry a dragon raised upon a pole is constantly represented near a figure, whilst the words 'Hic Harold' prove to be intended for Harold; yet Matthew of Westminster, in describing a battle fought in the time of Edward I., says that the place of the king was 'between the dragon and the standard,' which seems to imply that the standard or banner had some other device. The dragon was perhaps a kind of standard borne to indicate the presence of the king. Henry III. carried one at the Battle of Lewes, fought against Simon de Montfort in 1264:

[paragraph continues] It was not, however, at that time restricted to the King, for Simon himself in the same battle

[paragraph continues] The English at the Battle of Crecy carried a 'burning dragon, made of red silk adorned and beaten with very broad and fair lilies of gold, and broidered about with gold and vermilion.' This banner," adds Miss Millington, perhaps resembled that used by the Parthians and Dacians, which is described by Ammianus Marcellinus as 'a dragon, formed of purple stuff; resplendent with gold and precious stones fixed on a long pike, and so contrived that when held in a certain manner, with its mouth to the wind, the entire body became inflated, and stretched its sinuous length upon the air.'"

"The dragon," says Mr. Planché, "was the customary standard of the kings of England from the time of the Conquest. It was borne in the battle between Canute and Edmund Ironside; it is figured in the Bayeux tapestry, and there are directions for making one in the reign of Henry III., but it never formed a portion of their armorial bearings, i.e., as a charge upon the shield of arms."

Henry VII., first of the Tudor line, assumed as one of his badges the red dragon of Cadwallader—

[paragraph continues] "Red dragon dreadful." Henry claimed an uninterrupted descent from the aboriginal princes of Britain, Arthur and Uther, Caradoc, Halstan, Pendragon, &c. His grandfather, Owen Tudor, bore a dragon as his device in proof of his descent from Cadwallader, the last British prince and first King of Wales (678 A.D.), the dragon being the ensign of that monarch. At the Battle of Bosworth Field Henry bore the dragon standard. After the battle of Bosworth Field Henry went in state to St. Paul's, where he offered three standards. On one was the image of St. George, on the other a "red fierce dragon beaten upon green and white sarsenet" (the livery colours of the House of Tudor); on the third was painted a dun cow upon yellow tartan,—the dun cow, in token of his descent from Guy Earl of Warwick, who had slain

[paragraph continues] The dun cow is still one of the badges of the Guards. This monarch founded the office of Rouge dragon pursuivant on the day before his coronation (October 29, 1485). Henry VII., Henry VIII., Edward V., Mary and Elizabeth all carried the dragon as a supporter to the royal arms, but varied in position, and at times superseded by a greyhound. (A greyhound argent, collared or, the collar charged with a rose gules, was a Lancastrian badge.) Henry VIII. used for supporters the red dragon and

white greyhound of his family; a red dragon and a lion gardant gold, sometimes crowned; at other times a silver greyhound and a golden lion, an antelope, a white bull, a cock, &c. On the union of Scotland and England under King James, the Scottish unicorn was substituted for the sinister supporter, while the lion gardant, first adopted by Henry VIII., appears to have permanently superseded the red dragon of Wales, the white greyhound, &c., as the other supporter of the royal arms, the dragon being relegated to be the special badge of the principality of Wales, which position it still retains. The present royal badges, as settled at the union, 1801, are:

|

A white rose within a red |

England. |

|

A thistle |

Scotland. |

|

A harp or, stringed argent, and a trefoil or shamrock vert |

Ireland. |

|

Upon a mount vert, a dragon passant, wings expanded and endorsed, gules |

Wales. |

Richard III. as a badge had a black dragon. "The bages that he beryth by the Earldom of Wolsr (Ulster) ys a blacke dragon," derived through his mother from the De Burghs, Earls of Ulster.

Mallet, in his "Northern Antiquities," states "that the thick misshapen walls winding round a rude fortress at the summit of a rock were called by a name signifying dragon, and as women of distinction

were, during the ages of chivalry, commonly placed in such castles for security, thence arose the romances of princesses of great beauty being guarded by dragons, and afterwards delivered by young heroes

|

The dragon has always been an honourable bearing in British armoury, in some instances to commemorate a triumph over a mighty foe, or merely for the purpose of inspiring the enemy with terror. This seems to have been especially the case with the dragon standard—the "red dragon dreadful" of Wales (y Ddraig Coch) described as:

86:* Brewer's "Dictionary of Phrase and Fable."