The Algonquin Legends of New England, by Charles G. Leland, [1884], at sacred-texts.com

The Algonquin Legends of New England, by Charles G. Leland, [1884], at sacred-texts.com

(Micmac.)

N'kah-nee-oo. In the old time (P.) Glooskap came to Pulewech Munegoo (M., Partridge Island), and here he met with Kitpooseagunow, 1 whose mother had been slain by a fearful cannibal giant. And it was against these that he made war all his life long, as did Glooskap. Whence it came to pass that they loved one another, which did not at all hinder them from having a hearty and merry encounter, in which they missed but little of killing one or the other, and all in the best natured way in the world.

Now, having come to Pulewech Munegoo, the lord

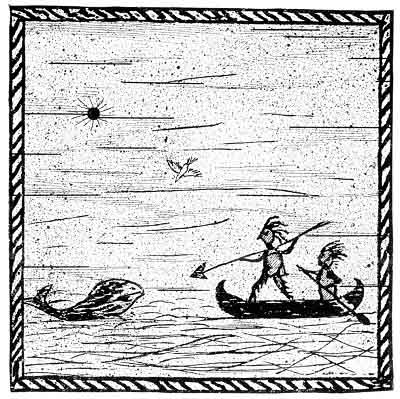

GLOOSKAP AND KEANKE SPEARING THE WHALE.

of men and beasts was entertained by Kitpooseagunow. And when the night came, he who was born after his mother's death said to his guest, "Let us go on the sea in a canoe and catch whales by torchlight;" to which Glooskap, nothing loath, consented, for he was a mighty fisherman, as are all the Wabanaki of the seacoast. 1

Now when they came to the beach there were only great rocks, lying here and there; but Kitpooseagunow, lifting the largest of these, put it on his head, and it became a canoe. And picking up another, it turned to a paddle, while a long splinter which he split from a ledge seemed to be a spear. Then Glooskap asked, "Who shall sit in the stern and paddle, and who will take the spear?" Kitpooseagunow said, "That will I." So Glooskap paddled, and soon the canoe passed over a mighty whale; in all the great sea there was not his like; but he who held the spear sent it like a thunderbolt down into the waters, and as the handle rose again to sight he snatched it up, and the great fish was caught. And as Kitpooseagunow whirled it on high, the whale, roaring, touched the clouds. Then taking him from the point, the fisher

tossed him into the bark as if he had been a trout. And the giants laughed; the sound of their laughter was heard all over the land of the Wabanaki. And being at home, the host took a stone knife and split the whale, and threw one half to the guest Glooskap, and they roasted each his piece over the fire and ate it.

Now the Master, having marked the light, which was long in the heaven after the sun went clown, said, "The sky is red; we shall have a cold night." And his host understood him well, and saw that he would make it cold by magic. So he bade Marten bring in all the fuel he could find, and all there was of the oil of a porpoise; and this oil he so multiplied by magic that there was ten times more of it. And they sat them down and smoked, and told tales of old times; but it grew ever colder and colder. And at midnight, when all was burnt out, Marten froze to death, and then the grandmother, but the two giants smoked on, and laughed and talked. Then the rocks out-of-doors split with the cold, the great trees in the forest split; the sound thereof was as thunder, but the Master and he who was born after his mother's death laughed even louder. And so they sat until the sun rose. Then Glooskap said to the dead woman, "Noogume, numchahse!" (M.) Grandmother, arise!" and to his boy, "Abistanooch numchahse!" "Marten, arise!" and they arose, and went about their work.

And the morning being bright, they went forth far into the forest to find game. But they got very little, for they caught only one small beaver, and Glooskap

gave up his share of this to Kitpooseagunow. And he, taking the skin, fastened it to his garter, whence it dangled like the skin of a mouse at the knee of a tall man. But as he went on through the woods the skin grew larger and larger and larger, till it broke away by its own weight. Then the giant twisted a mighty sapling into a withe, and fastened it around his waist. But it still grew apace as he went on, till, trailing after, it tore down all the forest, pulling away the trees, so that Kitpooseagunow left a clean, fair road behind him. 1

And when the night came on they fished again, as they had done before; and again it was said, but this time by the host, "The sky is red; we shall have a cold night." So they heaped up wood more than the first time, but now it was far colder. And soon the boy was dead, and the grandmother also lay frozen. But when the sun rose the Master brought them back to life, and, bidding good-by to Kitpooseagunow, went his way. 2

The most striking feature, however, of this legend is its Norse-like breadth or grandeur and its genial humor, which are very remarkable characteristics for the fictions of savages. Its resemblance to the Scandinavian tales is, if accidental, very remarkable. The two heroes are, like Thor and Odin, giant heroes who make war on Jötuns and Trolls; that is, giant-like sorcerers. It is their profession; they live in it. No one can read Beowulf without being struck by the great resemblance between Grendel, the hideous, semi-human night prowler, and the Kewahqu', a precisely similar monster, who rises from the depths of waters to wantonly murder man. I do not recall any two beings in any other two disconnected mythologies so strangely similar. The fishing for the whale re-calls that which is told in the Older Edda (Hymiskvida, 21), where Hymir succeeds in hooking two of these fish:—

"Then he and Hymir rowed out to sea. Thor rowed oft with two oars, and so powerfully that the giant was obliged to acknowledge they were speeding very fast. He himself rowed at the prow."

If the reader will compare this account of the Edda with the Micmac story, he cannot fail to be struck with the great resemblance between them. It

is even specified in both that the hero, though a guest, paddles. And in both instances the host catches a whale. Now compare with this the legend of Manobozho-Hiawatha, who merely catches the great sunfish, and is swallowed by it. Does it not seem as if the Western Indians had here borrowed from the Micmacs, and the Micmacs from the Norse? Whether this was done directly or through the Eskimo is as yet a problem. It may also be noted that both in the Edda and in the Micmac story, it is declared that one of the giants picked up the boat and carried it.

It may be observed that most of these Indian traditions were originally poems. It is probable that all were sung, while they still retained the character of serious mythical or sacred narrative. Now they are in the transition state of heroic tales. But they unquestionably still retain many passages of very great antiquity, and it is not impossible that Eskimo and even Norse songs are still preserved in them. In this tale the following coincidences with passages in the Elder Edda (Hymiskvida) are remarkable. In both the host asks his guest to go with him to catch whales, to which the latter assents.

"We three to-morrow night

Shall be compelled

On what we catch to live.'

Thor said he would

On the sea row."

Kitpooseagunow picks up the heavy canoe, with its oars and a spear, and carries them.

"Thor went,

grasped the prow

quickly with its hold-water,

lifted the boat

together with its oars

and scoop ;

bore to the dwelling

the curved vessel."

Glooskap, asks which of the two shall take the paddle, and which sit in the stern. Hymir inquires,--

"Wilt thou do

half the work with me?

either the whales

home to the dwelling bear,

Or the boat

fast bind?"

Kitpooseagunow drew up a whale.

"The mighty Hymir,

He alone

two whales drew

up with his hook."

After this whale-fishing, the Scandinavian giants at home have a trial of strength and endurance. Thor throws a cup at Hymir. This cup can only be broken on Hymir's head, which is of ice, and intensely hard.

"That is harder

than any cup."

This is therefore an effort on the part of Thor to overcome Cold. Hymir is the incarnation of Cold itself.

"The icebergs resounded

as the churl approached; p. 81

the thicket on his cheeks

was frozen.

In shivers flew the pillars

At the Jotun's glance."

That is, the frost cracks the stones and rocks. In the Indian tale the two giants try to see which can freeze the other. In both there is distinctly a contest, In the Norse tale Strength or Heat fights Frost; in the American, Frost is battled with by Frost as a rival.

It may be observed that the Indian tale is far from being perfect, and that in all probability the whole of it includes a fishing for the sea-serpent.

It is plainly set forth in the Edda that Cold may be overcome by a magic spell. Thus Groa (Grougaldr, 12) promises her son a rune to effect this:—

"A seventh (charm) I will sing thee

If on a mountain high

frost should assail thee,

deadly cold shall not

thy body injure,

nor draw it to thy limbs."

74:1 Kitpooseagunow, "one born after his mother's death," is a magician-giant, who plays in the Algonquin mythology a part only inferior to that of Glooskap, whom he in every way resembles. Both are benevolent, both make war on wicked sorcerers and evil wild beasts, and both, finally, are much like Gargantua and Pantagruel in their sense of humor. They are sometimes made the heroes of the same adventure in different stories. The true origin of the name, according to Mr. Rand, is as follows: "After a cow moose or caribou has been killed, her calf is sometimes taken out alive, and reared by hand. As may be supposed, the calf is very easily tamed. The animal thus born is called Kitpooseagunow, and from this a verb is formed which denotes the act."--Legends of the Mic Macs, Old Dominion Monthly, 1871.

This giant was also called the Protector of the Oppressed. He probably represents the Glooskap myth in another form.

75:1 Glooskap would seem to have been the prototype of the giant fisher so well known in song:—

"His rod was made of a sturdy oak,

His line, a cable, in storms ne'er broke

He baited his hook with a dragon's tail,

And sat on a rock and bobbed for whale.'

A fabulous monster, apparently identical with the dragon, is common in Micmac stories.

77:1 Many of these stories have received later additions, which can be detected by their occurring only in single versions of them. In the story of Kitpooseagunow (Rand's manuscript) the giants arrive at a "large town," and go to a "store," where they sell the skin for all the motley, goods, houses, and lands which the merchant possesses. "And the skin was so heavy that it took the greater part of the day to weigh it."

77:2 It is possible that there is a version of this story in which Glooskap kills his friend with frost, and then revives him. In one story it is a frozen stream, incarnate as a man, which attempts in vain to freeze Glooskap.

The extraordinary manner in which host and guest, or even p. 78 intimate friends, endeavor to kill one another in the most good-natured rivalry, is of constant occurrence in the Eskimo legends. It is not infrequent among our own backwoods or frontier-men.

The stone-canoe occurs in Eskimo legends (vide Rink), as it does in those of all American Indians.