Unwritten Literature of Hawaii, by Nathaniel B. Emerson, [1909], at sacred-texts.com

Unwritten Literature of Hawaii, by Nathaniel B. Emerson, [1909], at sacred-texts.com

A bird is easier captured than the notes of a song. The mele and oli of Hawaii's olden time have been preserved for us; but the music to which they were chanted, a less perdurable essence, has mostly exhaled. In the sudden transition from the tabu system to the new order of things that came in with the death of Kamehameha in 1819, the old fashion of song soon found itself antiquated and outdistanced. Its survival, so far as it did survive, was rather as a memorial and remembrance of the past than as a register of the living emotions of the present.

The new music, with its pa, ko, li--answering to our do, re, mi a--was soon in everybody's mouth. From the first it was evidently destined to enact a role different from that of the old cantillation; none the less the musical ideas that came in with it, the air of freedom from tabu and priestcraft it breathed, and the diatonic scale, the highway along which it marched to conquest, soon produced a noticeable reaction in all the musical efforts of the people. This new seed, when it had become a vigorous plant, began to push aside the old indigenous stock, to cover it with new growths, and, incredible as it may seem, to inoculate it with its own pollen, thus producing a cross which to-day is accepted in certain quarters as the genuine article of Hawaiian song. Even now. the people of northwestern America are listening with demonstrative interest to songs which they suppose to be those of the old hula, but which in reality have no more connection with that institution than our negro minstrelsy has to do with the dark continent.

The one regrettable fact, from a historical point of view, is that a record was not made of indigenous Hawaiian song before this process of substitution and adulteration had begun. It is no easy matter now to obtain the data for definite knowledge of the subject.

While the central purpose of this chapter will be a study of the music native to old Hawaii, and especially of that produced in the halau, Hawaiian music of later times and of the present day can not be entirely neglected; nor will it be without its value for the indirect light it will shed on ancient conditions and on racial characteristics. The reaction that has taken place in Hawaii within historic times in

response to the stimulus from abroad can not fail to be of interest in itself.

There is a peculiarity of the Hawaiian speech which can not but have its effect in determining the lyric tone-quality of Hawaiian music; this is the predominance of vowel and labial sounds in the language. The phonics of Hawaiian speech, we must remember, lack the sounds represented by our alphabetic symbols b, c or s, d, f, g, j, q, x, and z--a poverty for which no richness in vowel sounds can make amends. The Hawaiian speech, therefore, does not call into full play the uppermost vocal cavities to modify and strengthen, or refine, the throat and month tones of the speaker and to give reach and emphasis to his utterances. When he strove for dramatic and passional effect, he did not make his voice resound in the topmost cavities of the voice-trumpet, but left it to rumble and mutter low down in the throat-pipe, thus producing a feature that colors Hawaiian musical recitation.

This feature, or mannerism, as it might be called, specially marks Hawaiian music of the bombastic bravura sort in modern times, imparting to it in its strife for emphasis a sensual barbaric quality. It can be described further only as a gurgling throatiness, suggestive at times of ventriloquism, as if the singer were gloating over some wild physical sensation, glutting his appetite of savagery, the meaning of which is almost as foreign to us and as primitive as are the mewing of a cat, the gurgling of an infant, and the snarl of a mother-tiger. At the very opposite pole of development from this throat-talk of the Hawaiian must we reckon the highly-specialized tones of the French speech, in which we find the nasal cavities are called upon to do their full share in modifying the voice-sounds.

The vocal execution of Hawaiian music, like the recitation of much of their poetry, showed a surprising mastery of a certain kind of technique, the peculiarity of which was a sustained and continuous outpouring of the breath to the end of a certain period, when the lungs again drank their fill. This seems to have been an inheritance from the old religious style of prayer-recitation, which required the priest to repeat the whole incantation to its finish with the outpour of one lungful of breath. Satisfactory utterance of those old prayer-songs of the Aryans, the mantras, was conditioned likewise on its being a one-breath performance. A logical analogy may be seen between all this and that unwritten law, or superstition, which made it imperative for the heroes and demigods, kupua, of Hawaii's mythologic age to discontinue any unfinished work on the coming of daylight. a

When one listens for the first time to the musical utterance of a Hawaiian poem, it may seem only a monotonous onflow of sounds faintly punctuated by the primary rhythm that belongs to accent, but lacking those milestones of secondary rhythm which set a period to such broader divisions as distinguish rhetorical and musical phrasing. Further attention will correct this impression and show that the Hawaiians paid strict attention not only to the lesser rhythm which deals with the time and accent of the syllable, but also to that more comprehensive form which puts a limit to the verse.

With the Hawaiians musical phrasing was arranged to fit the verse of the mele, not to express a musical idea. The cadencing of a musical phrase in Hawaiian song was marked by a peculiarity all its own. It consisted of a prolonged trilling or fluctuating movement called i’i, in which the voice went up and down in a weaving manner, touching the main note that formed the framework of the melody, then springing away from it for some short interval--a half of a step, or even some shorter interval--like an electrified pith-ball, only to return and then spring away again and again until the impulse ceased. This was more extensively employed in the oli proper, the verses of which were longer drawn out, than in the mele such as formed the stock pieces of the hula. These latter were generally divided into shorter verses.

The musical instruments of the Hawaiians included many classes, and their study can not fail to furnish substantial data for any attempt to estimate the musical performances, attainments, and genius of the people.

Of drums, or drum-like instruments of percussion, the Hawaiians had four:

1. The pahu, or pahu-hula (pl. X), was a section of hollowed log. Bread-fruit and coconut were the woods generally used for this purpose. The tough skin of the shark was the choice for the drumhead, which was held in place and kept tense by tightening cords of coconut fiber, that passed down the side of the cylinder.

The workmanship of the pahu, though rude, was of tasteful design. So far as the author has studied them, each pahu was constructed with a diaphragm placed about two-thirds the distance from the head, obtained by leaving in place a cross section of the log, thus making a closed chamber of the drum-cavity proper, after the fashion of the kettledrum. The lower part of the drum also was hollowed out and carved, as will be seen in the illustration. In the carving of all the specimens examined the artists have shown a notable fondness for a fenestrated design representing a series of arches, after the fashion of

a two-storied arcade, the haunch of the superimposed arch resting directly on the crown of that below. In one case the lower arcade was composed of Roman, while the upper was of Gothic, arches. The grace of the design and the manner of its execution are highly pleasing, and suggest the inquiry, Whence came the opportunity for this intimate study of the arch?

The tone of the palm was produced by striking its head with the finger-tips, or with the palm of the hand; never with a stick, so far as the writer has been able to learn. Being both heavy and unwieldly, it was allowed to rest upon the ground, and, if used alone, was placed to the front of the operator; if sounded in connection with the instrument next to be mentioned, it stood at his left side.

The pahu, if not the most original, was the most important instrument used in connection with the hula. The drum, with its deep and solemn tones, is an instrument of recognized efficiency in its power to stir the heart to more vigorous pulsations, and in all ages it has been relied upon as a means of inspiring emotions of mystery, awe, terror, sublimity, or martial enthusiasm.

Tradition of the most direct sort ascribes the introduction of the pahu to La’a--generally known as La’a-mai-Kahiki (La’a-from-Kahiki)--a prince who flourished about six centuries ago. He was of a volatile, adventurous disposition, a navigator of some renown, having made the long voyage between Hawaii and the archipelagoes in the southern Pacific--Kahiki--not less than twice in each direction. On his second arrival from the South he brought with him the big drum, the pahu, which he sounded as he skirted the coast quite out to sea, to the wonder and admiration of the natives on the land. La’a, being of an artistic temperament and an ardent patron of the hula, at once gave the divine art of Laka the benefit of this newly imported instrument. He traveled from place to place, instructing the teachers and inspiring them with new ideals. It was he also who introduced into the hula the kaékeéke as an instrument of music.

2. The pu-niu (pl. XVI) was a small drum made from the shell of a coconut. The top part, that containing the eyes, was removed, and the shell having been smoothed and polished, the opening was tightly covered with the skin of some scaleless fish--that of the kala (Acanthurus unicornis) was preferred. A venerable kumu-hula states that it was his practice to use only the skin taken from the right side of the fish, because he found that it produced a finer quality of sound than that of the other side. The Hawaiian mind was very insistent on little matters of this sort--the mint, anise, and cummin of their system. The drumhead was stretched and placed in position while moist and flexible, and was then made fast to a ring-shaped cushion--poahu--of fiber or tapa that hugged the base of the shell.

The Hawaiians sometimes made use of the clear gum of the kukui tree to aid in fixing the drumhead in place.

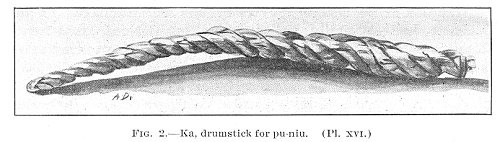

When in use the pu-niu was lashed to the right thigh for the convenience of the performer, who played upon it with a thong of braided fibers held in his right hand (), his left thus being free to manipulate the big drum that stood on the other side.

Of three pu-niu in the author's collection, one, when struck, gives off the sound of c+1 below the staff; another that of c+1♯ below the staff, and a third that of c+2♯ in the staff.

While the grand vibrations of the palm filled the air with their solemn tremor, the lighter and sharper tones of the pu-niu gave a piquancy to the effect, adding a feature which may be likened to the sparkling ripples which the breeze carves in the ocean's swell.

3. The ipu, or ipu-hula (pl. VII), though not strictly a drum, was a drumlike instrument. It was made by joining closely together two pear-shaped gourds of large size in such fashion as to make a body shaped like a figure 8. An opening was made in the upper end of

FIG. 2.--Ka, drumstick for pu-niu. (Pl. XVI.)

the smaller gourd to give exit to the sound. The cavities of the two gourds were thrown into one, thus making a single column of air, which, in vibration, gave off a note of clear bass pitch. An ipu of large size in the author's collection emits the tone of c in the bass. Though of large volume, the tone is of low intensity and has small carrying power.

For ease in handling, the ipu is provided about its waist with a loop of cord or tapa, by which device the performer was enabled to manipulate this bulky instrument with one hand. The instrument was sounded by dropping or striking it with well-adjusted force against the padded earth-floor of the Hawaiian house.

The manner and style of performing on the ipu varied with the sentiment of the mele, a light and caressing action when the feeling was sentimental or pathetic, wild and emphatic when the subject was such as to stir the feelings with enthusiasm and passion.

Musicians inform us that the drum--exception is made in the case of the snare and the kettle drum--is an instrument in which the pitch is a matter of comparative indifference, its function being to mark the time and emphasize the rhythm. There are other elements, it

Click to enlarge

PLATE XVI

PU-NIU, A DRUM

would seem, that must be taken into the account in estimating the value of the drum. Attention may be directed first to its tone-character, the quality of its note which touches the heart in its own peculiar way, moving it to enthusiasm or bringing it within the easy reach of awe, fear, and courage. Again, while, except in the orchestra, the drum and other instruments of percussion may require no exact pitch, still this does not necessarily determine their effectiveness. The very depth and gravity of its pitch, made pervasive by its wealth of overtones, give to this primitive instrument a weird hold on the emotions.

This combination of qualities we find well illustrated in the pahu and the ipu, the tones of which range in the lower registers of the human voice. The tone-character of the pu-niu, on the other hand, is more subdued, yet lively and cheerful, by reason in part of the very sharpness of its pitch, and thus affords an agreeable offset to the solemnity of the other two.

Ethnologically the palm is of more world-wide interest than any other member of its class, being one of many varieties of the kettle-drum that are to be found scattered among the tribes of the Pacific, all of them, perhaps, harking back to Asiatic forbears, such as the tom-tom of the Hindus.

The sound of the pahu carries one back in imagination to the dread sacrificial drum of the Aztec teocallis and the wild kettles of the Tartar hordes. The drum has cruel and bloody associations. When listening to its tones one can hardly put away a thought of the many times they have been used to drown the screams of some agonized creature.

For more purely local interest, inventive, originality, and simplicity, the round-bellied ipu takes the palm, a contrivance of strictly Hawaiian, or at least Polynesian, ingenuity. It is an instrument of fascinating interest, and when its crisp rind puts forth its volume of sound one finds his imagination winging itself back to the mysterious caverns of Hawaiian mythology.

The gourd, of which the ipu is made, is a clean vegetable product of the fields and the garden, the gift of Lono-wahine--unrecognized daughter of mother Ceres--and is free from all cruel alliances. No bleating lamb was sacrificed to furnish parchment for its drumhead. Its associations are as innocent as the pipes of Pan.

4. The Ka-éke-éke, though not drumlike in form, must be classed as an instrument of percussion from the manner of eliciting its note. It was a simple joint of bamboo, open at one end, the other end being left closed with the diaphragm provided by nature. The tone is produced by striking the closed end of the cylinder, while held in a vertical position, with a sharp blow against some solid, nonresonant body, such as the matted earth floor of the old Hawaiian house. In

the author's experiments with the kaékeéke an excellent substitute was found in a bag filled with sand or earth.

In choosing bamboo for the kaékeéke it is best to use a variety which is thin-walled and long-jointed, like the indigenous Hawaiian varieties, in preference to such as come from the Orient, all of which are thick-walled and short-jointed, and therefore less resonant than the Hawaiian.

The performer held a joint in each hand, the two being of different sizes and lengths, thus producing tones of diverse pitch. By making a proper selection of joints it would be possible to obtain a set capable of producing a perfect musical scale. The tone of the kaékeéke is of the utmost purity and lacks only sustained force and carrying power to be capable of the best effects.

An old Hawaiian once informed the writer that about the year 1850, in the reign of Kamehameha III, he was present at a hula kaékeéke given in the royal palace in Honolulu. The instrumentalists numbered six, each one of whom held two bamboo joints. The old man became enthusiastic as he described the effect produced by their performance, declaring it to have been the most charming hula he ever witnessed.

5. The úli-ulí () consisted of a small gourd of the size of one's two fists, into which were introduced shotlike seeds, such as those of the canna. In character it was a rattle, a noise-instrument pure and simple, but of a tone by no means disagreeable to the ear, even as the note produced by a woodpecker drumming on a log is not without its pleasurable effect on the imagination.

The illustration of the úliulí faithfully pictured by the artist reproduces a specimen that retains the original simplicity of the, instrument before the meretricious taste of modern times tricked it out with silks and feathers. (For a further description of this instrument, see p. 107.)

6. The pu-íli was also a variety of the rattle, made by splitting a long joint of bamboo for half its length into slivers, every alternate sliver being removed to give the remaining ones greater freedom and to make their play the one upon the other more lively, The tone is a murmurous breezy rustle that resembles the notes of twigs, leaves, or reeds struck against one another by the wind--not at all an unworthy imitation of nature-tones familiar to the Hawaiian ear.

The performers sat in two rows facing each other, a position that favored mutual action, in which each row of actors struck their instruments against those of the other side, or tossed them back and forth. (For further account of the manner in which the puili was used in the hula of the same name, see p. 113.)

7. The laau was one of the noise-instruments used in the hula. It consisted of two sticks of hard resonant wood, the smaller of which

was struck against the larger, producing a clear xylophonic note. While the pitch of this instrument is capable of exact determination, it does not seem that there was any attempt made at adjustment. A man in the author's collection, when struck, emits tones the predominant one of which is d+1 (below the staff).

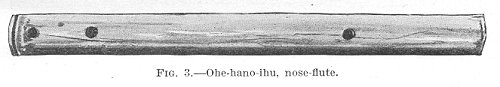

8. The ohe, or ohe-hano-ihu (), is an instrument of undoubted antiquity. In every instance that has come under the author's observation the material has been, as its name--ohe--signifies, a simple joint of bamboo, with an embouchure placed about half an inch from the closed end, thus enabling the player to supply the instrument with air from his right nostril. In every nose-flute examined there have been two holes, one 2 or 3 inches away from the embouchure, the older about a third of the distance from the open end of the flute.

The musician with his left hand holds the end of the pipe squarely against his lip, so that the right nostril slightly overlaps the edge of the embouchure. The breath is projected into the embouchure with modulated force. A nose-flute in the author's collection with the lower hole open produces the sound of f+1♯; with both holes unstopped

FIG. 3.--Ohe-hano-ihu, nose-flute.

it emits the sound a+2; and when both holes are stopped it produces the sound of c+2♯, a series of notes which are the tonic, mediant, and dominant of the chord of F♯ minor.

An ohe played by an old Hawaiian named Keaonaloa, an inmate of the Lunalilo Home, when both holes were stopped sounded f+1; with the lower hole open it sounded a+2, and when both holes were open it sounded c+3.

The music made by Keaonaloa with his ohe was curious, but not soul-filling. We must bear in mind, however, that it was intended only as an accompaniment to a poetical recitation.

Some fifty or sixty years ago it was not uncommon to see bamboo flutes of native manufacture in the hands of Hawaiian musicians of the younger generation. These instruments were avowedly imitations of the D-flute imported from abroad. The idea of using bamboo for this purpose must have been suggested by its previous use in the nose-flute.

"The tonal capacity of the Hawaiian nose-flute," says Miss Jennie Elsner, "which has nothing harsh and strident about it, embraces five tones, f+1 and g+2 in the middle register, and f+2, g+1, and a+2 an

octave above. These flutes are not always pitched to the same key, varying half a tone or so." On inquiring of the native who kindly furnished the following illustrations, he stated that he had bored the holes of his ohe without much measurement, trusting to his intuitions and judgment.

Click to enlarge

I--Range of the Nose-flute

The player began with a slow, strongly accented, rhythmical movement, which continued to grow more and more intricate. Rhythmical diminution continued in a most astounding manner until a frenzied climax was reached; in other words, until the player's breath-capacity was exhausted.

A peculiar effect, as of several instruments being used at the same time, was produced by the two lower tones being thrown in in wild profusion, often apparently simultaneously with one of the upper tones. As the tempo in any one of these increased, the rhythm was lost sight of and a peculiar syncopated effect resulted. a

Click to enlarge

II--Music from the Nose-flute

9. The pu-á was a whistle-like instrument. It was made from a gourd of the size of a lemon, and was pierced with three holes, or sometimes only two, one for the nose, by which it was blown, while

the others were controlled by the fingers. This instrument has been compared to the Italian ocarina.

10. The íli-íli was a noise-instrument pure and simple. It consisted of two pebbles that were held in the hand and smitten together, after the manner of castanets, in time to the music of the voices. (See p. 120.)

11. The niau-kani--singing splinter--was a reed-instrument of a rude sort, made by holding a reed of thin bamboo against a slit cut out in a larger piece of bamboo. This was applied to the mouth, and the voice being projected against it produced an effect similar to that of the jew's harp. (See p. 132.)

12. Even still more extemporaneous and rustic than any of these is a modest contrivance called by the Hawaiians pú-la-í. It is nothing more than a ribbon torn from the green leaf of the ti plant, say three-quarters of an inch to an inch in width by 5 or 6 inches long, and rolled up somewhat after the manner of a lamplighter, so as to form a squat cylinder an inch or more in length. This was compressed to flatten it. Placed between the lips and blown into with proper force, it emits a tone of pure reedlike quality, that varies in pitch, according to the size of the whistle, from G in the middle register to a shrill piping note more than an octave above.

The hula girl who showed this simple device offered it in answer to reiterated inquiries as to what other instruments, besides those of more formal make already described, the Hawaiians were wont to use in connection with their informal rustic dances. "This," said she, "was sometimes used as an accompaniment to such informal dancing as was indulged in outside the halau." This little rustic pipe, quickly improvised from the leaf that every Hawaiian garden supplies, would at once convert any skeptic to a belief in the pipes of god Pan.

13. The ukeké, the one Hawaiian instrument of its class, is a mere strip of wood bent into the shape of a bow that its elastic force may keep tense the strings that are stretched upon it. These strings, three in number, were originally of sinnet, later after the arrival of the white man, of horsehair. At the present time it is the fashion to use the ordinary gut designed for the violin or the taro-patch guitar. Every ukeké seen followed closely a conventional pattern, which argues for the instrument a historic age sufficient to have gathered about itself some degree of traditional reverence. One end of the stick is notched or provided with holes to hold the strings, while the other end is wrought into a conventional figure resembling the tail of a fish and serves as an attachment about which to wind the free ends of the strings.

No ukeké seen by the author was furnished with pins, pegs, or any similar device to facilitate tuning. Nevertheless, the musician does

tune his ukeké as the writer can testify from his own observation. This Hawaiian musician was the one whose performances on the nose-flute are elsewhere spoken of. When asked to give a sample of his playing on the ukeké, he first gave heed to his instrument as if testing whether it was in tune. He was evidently dissatisfied and pulled at one string as if to loosen it; then, pressing one end of the bow against his lips, he talked to it in a singing tone, at the same time plucking the strings with a delicate rib of grass. The effect was most pleasing. The open cavity of the mouth, acting as a resonator, reenforced the sounds and gave them a volume and dignity that was a revelation. The lifeless strings allied themselves to a human voice and became animated by a living soul.

With the assistance of a musical friend it was found that the old Hawaiian tuned his strings with approximate correctness to the tonic, the third and the fifth. We may surmise that this self-trained musician had instinctively followed the principle or rule proposed by Aristoxenus, who directed a singer to sing his most convenient note, and then, taking this as a starting point, to time the remainder of his strings--the Greek kithara, no doubt--in the usual manner from this one.

While the ukeké was used to accompany the mele and the oli, its chief employment was in serenading and serving the young folk in breathing their extemporized songs and uttering their love-talk--hoipoipo. By using a peculiar lingo or secret talk of their own invention, two lovers could hold private conversation in public and pour their loves and longings into each other's ears without fear of detection--a thing most reprehensible in savages. This display of ingenuity has been the occasion for outpouring many vials of wrath upon the sinful ukeké.

Experiment with the ukeké impresses one with the wonderful change in the tone of the instrument that takes place when its lifeless strings are brought into close relation with the cavity of the mouth. Let anyone having normal organs of speech contract his lips into the shape of an O, make his cheeks tense, and then, with the pulp of his finger as a plectrum, slap the center of his cheek and mark the tone that is produced. Practice will soon enable him to render a full octave with fair accuracy and to perform a simple melody that shall be recognizable at a short distance. The power and range this acquired will, of course, be limited by the skill of the operator. One secret of the performance lies in a proper management of the tongue. This function of the mouth to serve as a resonant cavity for a musical instrument is familiarly illustrated in the jew's-harp.

The author is again indebted to Miss Elsner for the following comments on the ukeké:

The strings of this ukeké, the Hawaiian fiddle, are tuned to e+1, to b and to d+1. These three strings are struck nearly simultaneously, but the sound being very feeble, it is only the first which, receiving the sharp impact of the blow, gives out enough volume to make a decided impression.

Click to enlarge

III--The Ukeké (as played by Keaonaloa)

The early visitors to these islands, as a rule, either held the music of the savages in contempt or they were unqualified to report on its character and to make record of it.

We know that in ancient times the voices of the men as well as of the women were heard at the same time in the songs of the hula. One of the first questions that naturally arises is, Did the men and the women sing in parts or merely in unison?

It is highly gratifying to find clear historical testimony on this point from a competent authority. The quotation that follows is from the pen of Capt. James King, who was with Capt. James Cook on the latter's last voyage, in which he discovered the Hawaiian islands (January 18, 1778). The words were evidently penned after the death of Captain Cook, when the writer of them, it is inferred, must have succeeded to the command of the expedition. The fact that Captain King weighs his words, as evidenced in the footnote, and that he appreciates the bearing and significance of his testimony, added to the fact that he was a man of distinguished learning, gives unusual weight to his statements. The subject is one of so great interest and importance, that the whole passage is here quoted. a It adds not a little to its value that the writer thereof did not confine his remarks to the music, but enters into a general description of the hula. The only regret is that he did not go still further into details.

Their dances have a much nearer resemblance to those of the New Zealanders than of the Otaheitians or Friendly Islanders. They are prefaced with a slow, solemn song, in which all the party join, moving their legs, and gently striking their breasts in a manner and with attitudes that are perfectly easy and graceful; and so far they are the same with the dances of the Society Islands. When this has lasted about ten minutes, both the tune and the motions gradually quicken, and end only by their inability to support the fatigue, which

part of the performance is the exact counterpart of that of the New Zealanders; and (as it is among them) the person who uses the most violent action and holds out the longest is applauded as the best dancer. It is to be observed that in this dance the women only took part and that the dancing of the men is nearly of the same kind with what we saw at the Friendly Islands; and which may, perhaps, with more propriety, be called the accompaniment of the songs, with corresponding and graceful motions of the whole body. Yet as we were spectators of boxing exhibitions of the same kind with those we were entertained with at the Friendly Islands, it is probable that they had likewise their grand ceremonious dances, in which numbers of both sexes assisted.

Their music is also of a ruder kind, having neither flutes nor reeds, nor instruments of any other sort, that we saw, except drums of various sizes. But their songs, which they sing in parts, and accompany with a gentle motion of the arms, in the same manner as the Friendly Islanders, had a very pleasing effect.

To the above Captain King adds this footnote:

As this circumstance of their singing in parts has been much doubted by persons eminently skilled in music, and would be exceedingly curious if it was clearly ascertained, it is to be lamented that it can not be more positively authenticated.

Captain Burney and Captain Phillips of the Marines, who have both a tolerable knowledge of music, have given it as their opinion they did sing in parts; that is to say, that they sang together in different notes, which formed a pleasing harmony.

These gentlemen have fully testified that the Friendly Islanders undoubtedly studied their performances before they were exhibited public; that they had an idea of different notes being useful in harmony; and also that they rehearsed their compositions in private and threw out the inferior voices before they ventured to appear before those who were supposed to be judges of their skill in music.

In their regular concerts each man had a bamboo a which was of a different length and gave a different tone. These they beat against the ground, and each performer, assisted by the note given by this instrument, repeated the same note, accompanying it with words, by which means it was rendered sometimes short and sometimes long. In this manner they sang in chorus, and not only produced octaves to pitch other, according to their species of voice, but fell on concords such as were not disagreeable to the ear.

Now, to overturn this fact, by the reasoning of persons who did not hear these performances, is rather an arduous task. And yet there is great improbability that any uncivilized people should by accident arrive at this perfection in the art of music, which we imagine can only be attained by dint of study and knowledge of the system and the theory on which musical composition is founded. Such miserable jargon as our country psalm-singers practice, which may be justly deemed the lowest class of counterpoint, or singing in several parts, can not be acquired in the coarse manner in which it is performed in the churches without considerable time and practice. It is, therefore, scarcely credible that a people, semibarbarous, should naturally arrive at any perfection in that art which it is much doubted whether the Greeks and Romans, with all their refinements in music, ever attained, and which the Chinese, who have been longer civilized than any people on the globe, have not yet found out.

If Captain Burney (who, by the testimony of his father, perhaps the greatest musical theorist of this or any other age, was able to have done it) has written down in European notes the concords that these people sung, and if these concords had been such as European ears could tolerate, there would have been no longer doubt of the fact; but, as it is, it would, in my opinion, be a rash judgment to venture to affirm that they did or did not understand counterpoint; and therefore I fear that this curious matter must be considered as still remaining undecided. (A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean, undertaken by the command of His Majesty, for making discoveries in the Northern Hemisphere. Performed under the direction of Captains Cook, Clerke, and Gore, in His Majesty's ships the Resolution and Discovery, in the years 1776, 1777, 1778, and 1780, 3 volumes, London, 1784, III, 2d ed., 142, 143, 144.)

While we can not but regret that Captain King did not go into detail and inform us specifically what were the concords those old-time people "fell on," whether their songs were in the major or minor key, and many other points of information, he has, nevertheless, put science under obligations to him by his clear and unmistakable testimony to the fact that they did arrange their music in parts. His testimony is decisive: "In this manner they sang in chorus, and not only produced octaves to each other, according to their species of voice, but fell on concords such as were not disagreeable to the ear." When the learned doctor argues that to overturn this fact would be an arduous task, we have to agree with him--an arduous task indeed. He well knew that one proven fact can overthrow a thousand improbabilities. "What man has done man can do" is a true saying; but it does not thence follow that what man has not done man can not do.

If the contention were that the Hawaiians understood counter-point as a science and a theory, the author would unhesitatingly admit the improbability with a readiness akin to that with which he would admit the improbability that the wild Australian understood the theory of the boomerang. But that a musical people, accustomed to pitch their voices to the clear and unmistakable notes of bamboo pipes cut to various lengths, a people whose posterity one generation later appropriated the diatonic scale as their own with the greatest avidity and readiness, that this people should recognize the natural harmonies of sound, when they had chanced upon them, and should imitate them in their songs--the improbability of this the author fails to see.

The clear and explicit statement of Captain King leaves little to be desired so far as this sort of evidence can go. There are, however, other lines of inquiry that must be developed:

1. The testimony of the Hawaiians themselves on this matter. This is vague. No one of whom inquiry has been made is able to affirm positively the existence of part-singing in the olden times. Most of those with whom the writer has talked are inclined to the view that the ancient cantillation was not in any sense part-singing as now practised. One must not, however, rely too much on such

testimony as this, which at the best is only negative. In many cases it is evident the witnesses do not understand the true meaning and bearing of the question. The Hawaiians have no word or expression synonymous with our expression "musical chord." In all inquiries the writer has found it necessary to use periphrasis or to appeal to some illustration. The fact must be borne in mind, however, that people often do a thing, or possess a thing, for which they have no name.

2. As to the practice among Hawaiians at the present time, no satisfactory proof has been found of the existence of any case in which in the cantillations of their own songs the Hawaiians--those uninfluenced by foreign music--have given an illustration of what can properly be termed part-singing; nor can anyone be found who can testify affirmatively to the same effect. Search for it has thus far been as fruitless as pursuit of the will-o’-the-wisp.

3. The light that is thrown on this question by the study of the old Hawaiian musical instruments is singularly inconclusive. If it were possible, for instance, to bring together a complete set of kaekeeke bamboos which were positively known to have been used together at one performance, the argument from the fact of their forming a musical harmony, if such were found to be the case--or, on the other hand, of their producing only a haphazard series of unrelated sounds, if such were the fact--would bring to the decision of the question the overwhelming force of indirect evidence. Put such an assortment the author has not been able to find. Bamboo is a frail and perishable material. Of the two specimens of kaekeeke tubes found by him in the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum one was cracked and voiceless; and so the testimony of its surviving partner was of no avail.

The Hawaiians of the present day are so keenly alive to musical harmony that it is hardly conceivable that their ancestors two or three generations ago perpetrated discords in their music. They must either have sung in unison or hit on "concords such as were not disagreeable to the ear." If the music heard in the halau to-day in any close degree resembles that of ancient times--it must be assumed that it does--no male voice of ordinary range need have found any difficulty in sounding the notes, nor do they scale so low that a female voice would not easily reach them.

Granting, then, as we must, the accuracy of Captain King's statement, the conclusion to which the author of this paper feels forced is that since the time of the learned doctor's visit to these shores, more than one hundred and twenty-eight years ago, the art and practice of singing or cantillating after the old fashion has declined among the Hawaiians. The hula of the old times, in spite of all the efforts to maintain it, is becoming more and more difficult of procurement

every day. Almost none of the singing that one hears at the so-called hula performances gotten up for the delectation of sight-seers is Hawaiian music of the old sort. It belongs rather to the second or third rattoon-crop, which has sprung up under the influence of foreign stimuli. Take the published hula songs, such as "Tomi-tomi," "Wahine Poupou" and a dozen others that might be mentioned, to say nothing about the words--the music is no more related to the genuine Hawaiian article of the old times than is "ragtime" to a Gregorian chant.

The bare score of a hula song, stripped of all embellishments and reduced by the logic of our musical science to the merest skeleton of notes, certainly makes a poor showing and gives but a feeble notion of the song itself--its rhythm, its multitudinous grace-notes, its weird tone-color. The notes given below offer such a skeletal presentation of a song which the author heard cantillated by a skilled hula-master. They were taken down at the author's request by Capt. H. Berger, conductor of the Royal Hawaiian Baud:

Click to enlarge

IV--Song from the Hula Pa’i-umauma

The same comment may be made on the specimen next to be given as on the previous one: there is an entire omission of the trills and flourishes with which the singer garlanded his scaffolding of song, and which testified of his adhesion to the fashion of his ancestors, the fashion according to which songs have been sung, prayers recited, brave deeds celebrated since the time when Pane and Pele and the other gods dipped paddle for the first time into Hawaiian waters. Unfortunately, in this as in the previous piece and as in the one next to be given, the singer escaped the author before he was able to catch the words.

Click to enlarge

V--Song from the Hula Pa-ipu

Here, again, is a piece of song that to the author's ear bears much the same resemblance to the original that an oiled ocean in calm would bear to the same ocean when stirred by a breeze. The fine dimples which gave the ocean its diamond-flash have been wiped out.

Click to enlarge

VI--Song for the Hula Pele

Is it our ear that is at fault? Is it not rather our science of musical notation, in not reproducing the fractions of steps, the enharmonics that are native to the note-carving ear of the Chinaman, and that are perhaps essential to the perfect scoring of an oli or mele as sung by a Hawaiian?

None of the illustrations thus far given have caught that fluctuating trilling movement of the voice which most. musicians inter-viewed on the subject declare to be impossible of representation, while some flout the assertion that it represents a change of pitch. One is reminded by this of a remark made by Pietro Mascagni: a

The feeling that a people displays in its character, its habits, its nature, and thus creates an overprivileged type of music, may be apprehended by a foreign spirit which has become accustomed to the usages and expressions common from that particular people. But popular music, [being] void of any scientific basis, will always remain incomprehensible to the foreigner who seeks to study it technically.

When we consider that the Chinese find pleasure in musical performances on instruments that divide the scale into intervals less than half a step, and that the Arabian musical scale included quarter-steps, we shall be obliged to admit that this statement of Mascagni is not merely a fling at our musical science.

Here are introduced the words and notes of a musical recitation done after the manner of the hula by a Hawaiian professional and his wife. Acquaintance with the Hawaiian language and a feeling for the allusions connoted in the text of the song would, of course, be a great aid in enabling one to enter into the spirit of the performance. As these adjuncts will be available to only a very few

of those who will read these words, in the beginning are given the words of the oli with which he prefaced the song, with a translation of the same, and then the mele which formed the bulk of the song, also with a translation, together with such notes and comments as are necessary to bring one into intellectual and sympathetic relation with the performance, so far as that is possible under the circumstances. It is especially necessary to familiarize the imagination with the language, meaning, and atmosphere of a mele, because the Hawaiian approached song from the side of the. poet and elocutionist. Further discussion of this point must, however, be deferred to another division of the subject:

He Oli

[Translation]

A Song

The mele to which the above oli was prelude is as follows:

Mele

Click to enlarge

VII--Oli and Mele from the Hula Ala’a-papa

Click to enlarge

VII--Oli and Mele from the Hula Ala’a-papa

[Translation]

Song from the Hula Ala’apapa

EXPLANATORY REMARKS

The acute or stress accent is placed over syllables that take the accent in ordinary speech.

A word or syllable italicized indicates drum-down-beat.

It will be noticed that the stress-accent and the rhythmic accent, marked by the down-beat, very frequently do not coincide. The time marked by the drum-down-beat was strictly accurate throughout.

The tune was often pitched on some other key than that in which it is here recorded. This fact was noted when, from time to time, it was found necessary to have the singer repeat certain passages.

The number of measures devoted to the i’i, or fluctuation, which is indicated by the wavering line

, varied from time to time, even when the singer repeated the same passage. (See remarks on the i’i, p. 140.)

, varied from time to time, even when the singer repeated the same passage. (See remarks on the i’i, p. 140.)

Redundancies of speech (interpolations) which are in disagreement with the present writer's text (pp. 155-156) are inclosed in brackets. It will be seen that in the fifth verse he gives the version Maka’u ke kanaka i ka lehua instead of the one given by the author, which is Maka’u ka Lehua i ke kanaka. Each version has its advocates, and good arguments are made in favor of each.

On reaching the end of a measure that coincided with the close of a rhetorical phrase the singer, Kualii, made haste to snatch, as it were, at the first word or syllable of the succeeding phrase. This is indicated by the word "anticipating," or "anticipatory "--written anticip.--placed over the syllable or word thus snatched.

It was somewhat puzzling to determine whether the tones which this man sang were related to each other as five and three of the major key, or as three and one of the minor key. Continued and strained attention finally made it seem evident that it was the major key which he intended, i. e., it was f+1 and d+1 in the key of B♭, rather than f+1 and d+1 in the key of D minor.

In their ordinary speech the Hawaiians were good elocutionists--none better. Did they adhere to this same system of accentuation in their poetry, or did they punctuate their phrases and words according to the notions of the song-maker and the conceived exigencies of poetical composition? After hearing and studying this recitation of Kualii the author is compelled to say that he does depart in a great measure from the accent of common speech and charge his words with intonations and stresses peculiar to the mele. What artificial influence has come in to produce this result? Is it from some demand of poetic or of musical rhythm? Which? It was observed that he substituted the soft sound of t for the stronger sound of k, "because," as he explained, "the sound of the t is lighter." Thus he said te tanata instead of ke kanaka, the man. The Hawaiian ear has always a delicate feeling for tone-color.

In all our discussions and conclusions we must bear in mind that the Hawaiian did not approach song merely for its own sake; the song did not sing of itself. First in order came the poem, then the rhythm of song keeping time to the rhythm of the poetry. The Hawaiian sang not from a mere bubbling up of indefinable emotion, but because he had something to say for which he could find no other adequate form of expression. The Hawaiian boy, as he walks the woods, never whistles to keep his courage up. When he paces the dim aisles of Kaliuwa’a, he sets up an altar and heaps on it a sacrifice of fruit and flowers and green leaves, but he keeps as silent as a mouse.

During his performance Kualii cantillated his song while handling a round wooden tray in place of a drum; his wife meanwhile performed the dance. This she did very gracefully and in perfect time. In marking the accent the left foot was, if anything, the favorite, yet each foot in general took two measures; that is, the left marked the down-beat in measures 1 and 2, 5 and 6, and so on, while the right, in turn, marked the rhythmic accent that comes with the down-beat in measures 3 and 4, 7 and 8, and so on. During the four steps taken by the left foot, covering the time of two measures, the body was gracefully poised on the other foot. Then a shift was made, the position was reversed, and during two measures the emphasis came on the right foot.

The motions of the hands, arms, and of the whole body, including the pelvis--which has its own peculiar orbital and sidelong swing were in perfect sympathy one part with another. The movements were so fascinating that one was at first almost hypnotized and disqualified for criticism and analytic judgment. Not to derogate from the propriety and modesty of the woman's motions, under the influence of her Delsartian grace one gained new appreciation of "the charm of woven paces and of waving hands."

Throughout the whole performance of Kualii and his wife Abigaila it was noticed that, while he was the reciter, she took the part of the olapa (see p. 28) and performed the dance; but to this rôle she added that of prompter, repeating to him in advance the words of the next verse, which he then took up. Her verbal memory, it was evident, was superior to his.

Experience with Kualii and his partner, as well as with others, emphasizes the fact that one of the great difficulties encountered in the attempt to write out the slender thread of music (leo) of a Hawaiian mele and fit to it the words as uttered by the singer arises from the constant interweaving of meaningless vowel sounds. This, which the Hawaiians call i’i, is a phenomenon comparable to the weaving of a vine about a framework, or to the pen-flourishes that

illuminate old German text. It consists of the repetition of a vowel sound--generally i (= ee) or e (= a, as in fate), or a rapid interchange of these two. To the ear of the author the pitch varies through an interval somewhat less than a half-step. Exactly what is the interval he can not say. The musicians to whom appeal for aid in determining this point has been made have either dismissed it for the most part as a matter of little or no consequence or have claimed the seeming variation in pitch was due simply to a changeful stress of voice or of accent. But the author can not admit that the report of his senses is here mistaken.

A further embarrassment comes from the fact that this tone-embroidery found in the i’i is not a fixed quantity. It varies seemingly with the mood of the singer, so that not unfrequently, when one asks for the repetition of a phrase, it will, quite likely, be given with a somewhat different wording, calling for a readjustment of the rhythm on the part of the musician who is recording the score. But it must be acknowledged that the singer sticks to his rhythm, which, so far as observed, is in common time.

In justice to the Hawaiian singer who performs the accommodating task just mentioned it must be said that, under the circumstances in which he is placed, it is no wonder that at times he departs front the prearranged formula of song. His is the difficult task of pitching his voice and maintaining the same rhythm and tempo unaided by instrumental accompaniment or the stimulating movements of the dance. Let any stage-singer make the attempt to perform an aria, or even a simple recitative, off the stage, and without the support--real or imaginary--afforded by the wonted orchestral accompaniment as well as the customary stage-surroundings, and he will be apt to find himself embarrassed. The very fact of being compelled to repeat is of itself alone enough to disconcert almost anyone. The men and women who to-day attempt the forlorn task of reproducing for us a hula mele or an oli under what are to them entirely unsympathetic and novel surroundings are, as a rule, past the prime of life, and not unfrequently acknowledge themselves to be failing in memory.

After making all of these allowances we must, it would seem, make still another allowance, which regards the intrinsic nature and purpose of Hawaiian song. It was not intended, nor was it possible under the circumstances of the case, that a Hawaiian song should be sung to an unvarying tempo or to the same key; and even in the words or sounds that make up its fringework a certain range of individual choice was allowed or even expected of the singer. This privilege of exercising individuality might even extend to the solid framework of the mele or oli and not merely to the filigree, the i’i, that enwreathed it.

It would follow from this, if the author is correct, that the musical critic of to-day must be content to generalize somewhat and must not be put out if the key is changed on repetition and if tempo and rhythm depart at times from their standard gait. It is questionable if even the experts in the palmy days of the hula attained such a degree of skill as to be faultless and logical in these matters.

It has been said that modern music has molded and developed it-self under the influence of three causes, (1) a comprehension of the nature of music itself, (2) a feeling or inspiration, and (3) the influence of poetry. Guided by this generalization, it may be said that Hawaiian poetry was the nurse and pedagogue of that stammering infant, Hawaiian music; that the words of the mele came before its rhythmic utterance in song; and that the first singers were the priests and the eulogists. Hawaiian poetry is far ahead of Hawaiian song in the power to move the feelings. A few words suffice the poet with which to set the picture before one's eyes, and one picture quickly follows another; whereas the musical attachment remains weak and colorless, reminding one of the nursery pictures, in which a few skeletal lines represent the human frame.

Let us now for refreshment and in continued pursuit of our subject listen to a song in the language and spirit of old-time Hawaii, composed, however, in the middle of the nineteenth century. It is given as arranged by Miss Lillian Byington, who took it down as she heard it sung by an old Hawaiian woman in the train of Queen Liliuokalani, and as the author has since heard it sung by Miss Byington's pupils of the Kamehameha School for Girls. The song has been slightly idealized, perhaps, by trimming away some of the superfluous i’i, but not more than is necessary to make it highly acceptable to our ears and not so much as to take from it the plaintive bewitching tone that pervades the folk-music of Hawaii. The song, the mele, is not in itself much--a hint, a sketch, a sweep of the brush, a lilt of the imagination, a connotation of multiple images which no jugglery of literary art can transfer into any foreign speech. Its charm, like that of all folk-songs and of all romance, lies in its mysterious tug at the heartstrings.

Click to enlarge

VIII--He Inoa no Kamehameha

(Old Mele--Kindness of H. R. H. Liliuokalani)

He Inoa no Kamehameha

[Translation]

A Name-song of Kamehameha

The text of this mele--said to be a name-song of Kamehameha V--as first secured had undergone some corruption which obscured the meaning. By calling to his aid an old Hawaiian in whose memory the song had long been stored the author was able to correct it. Hawaiian authorities are at variance as to its meaning. One party reads in it an exclusive allusion to characters that have flitted across the stage within the memory of people now living, while another, taking a more romantic and traditional view, finds in it a reference to an old-time myth--that of Ke-anini-ula-o-ka-lani--the chief character in which was Haina-kolo. (See note e.) After carefully considering both sides of the question it seems to the author that, while the principle of double allusion, so common in Hawaiian poetry, may here prevail, one is justified in giving prominence to the historico-mythological interpretation that is inwoven in the poem. It is a comforting thought that adhesion to this decision will suffer certain unstaged actions of crowned heads to remain in charitable oblivion.

The music of this song is an admirable and faithful interpretation of the old Hawaiian manner of cantillation, having received at the hands of the foreign musician only so much trimming as was necessary to idealize it and make it reducible to our system of notation.

EXPLANATORY NOTE

Hoaeae.--This term calls for a quiet, sentimental style of recitation, in which the fluctuating trill i’i, if it occurs at all, is not made prominent. It is contrasted with the olioli, in which the style is warmer and the fluctuations of the i’i are carried to the extreme.

Thus far we have been considering the traditional indigenous music of the land. To come now to that which has been and is being produced in Hawaii by Hawaiians to-day, under influences from abroad, it will not be possible to mistake the presence in it of two strains: The foreign, showing its hand in the lopping away of much redundant foliage, has brought it largely within the compass of scientific and technical expression; the native element reveals itself, now in

plaintive reminiscence and now in a riotous bonhommie, a rollicking love of the sensuous, and in a style of delivery and vocal technique which demands a voluptuous throatiness, and which must be heard to be appreciated.

The foreign influence has repressed and well-nigh driven from the field the monotonous fluctuations of the i’i, has lifted the starveling melodies of Hawaii out of the old ruts and enriched them with new notes, thus giving them a spring and élan that appeal alike to the cultivated ear and to the popular taste of the day. It has, moreover, tapped the springs of folk-song that lay hidden in the Hawaiian nature. This same influence has also caused to germinate a Hawaiian appreciation of harmony and has endowed its music with new chords, the tonic and dominant, as well as with those of the subdominant and various minor chords.

The persistence of the Hawaiian quality is, however, most apparent in the language and imagery of the song-poetry. This will be seen in the text of the various mele and oli now to be given. Every musician will also note for himself the peculiar intervals and shadings of these melodies as well as the odd effects produced by rhythmic syncopation.

The songs must speak for themselves. The first song to be given, though dating from no longer ago than about the sixth decade of the last century, has already scattered its wind-borne seed and reproduced its kind in many variants, after the manner of other folklore. This love-lyric represents a type, very popular in Hawaii, that has continued to grow more and more personal and subjective in contrast with the objective epic style of the earliest Hawaiian mele.

Click to enlarge

IX--Song, Poli Anuanu

Click to enlarge

PLATE XVII

HAWAIIAN MUSICIAN PLAYING ON THE UKU-LELE

(By permission of Hubert Voss

Poli Anuanu

2. He anu e ka ua,

He anu e ka wai,

Li’a kuu ili

I ke anu, e.

3. Ina paha,

Ooe a owau

Ka i pu-kukú’i,

I ke anu, e.

He who would translate this love-lyric for the ear as well as for the mind finds himself handicapped by the limitations of our English speech--its scant supply of those orotund vowel sounds which flow forth with their full freight of breath in such words as a-ló-ha, pó-li, and á-nu-á-nu. These vocables belong to the very genius of the Hawaiian tongue.

[Translation]

Cold Breast

2. How bitter cold the rainfall,

Bitter cold the stream,

Body all a-shiver,

From the pinching cold.

3. Pray, what think you?

What if you and I

Should our arms enfold,

Just to keep off the cold?

The song next given, dating from a period only a few years subsequent, is of the same class and general character as Poli Anuanu. Both words and music are peculiarly Hawaiian, though one may easily detect the foreign influence that presided over the shaping of the melody.

Click to enlarge

X--Song, Hua-hua’i

Huahua’i

Chorus:

Kaua i ka huahua’i,

E uhene la’i pili koolua,

Pu-kuku’i aku i ke koekoe,

Anu lipo i ka palai.

[Translation]

Outburst

Chorus:

You and I, then, for an outburst!

Sing the joy of love's encounter,

Join arms against the invading damp,

Deep chill of embowering ferns.

The following is given, not for its poetical value and significance, but rather as an example of a song which the trained Hawaiian singer delights to roll out with an unctuous gusto that bids defiance to all description:

Click to enlarge

XI--Song, Ka Mawae

2 PILA = Two measures of an instrumental interlude.

NOTE.--The music to which this hula song is set was produced by a member of the Hawaiian Band, Mr. Solomon A. Hiram, and arranged by Capt. H. Berger, to whom the author is indebted for permission to use it.

Ka Mawae

Huli mai kou alo, ua anu wau,

Ua pulu i ka ua, malule o-luna.

[Translation]

The Refuge

Face now to my face; I'm smitten with cold,

Soaked with the rain and benumbed.

Click to enlarge

XII--Like no a Like

Like no a Like

Chorus:

Ooe no ka’u i upu ai,

Ku’u lei hiki ahiahi,

O ke kani o na manu,

I na hora o ke aumoe.

2. Maanei mai kaua,

He welina pa’a i ka piko,

A nau no wau i imi mai.

A loaa i ke aheahe a ka makani.

Chorus.

[Translation]

Resemblance

Chorus:

Thou art the end of my longing,

The crown of evening's delight,

When I hear the cock blithe crowing,

In the middle watch of the night.

2. This way is the path for thee and me,

A welcome warm at the end.

I waited long for thy coming,

And found thee in waft of the breeze.

Chorus.

Click to enlarge

XIII--Song, Pili Aoao

NOTE.--The composer of the music and the author of the reels was a Hawaiian named John Meha, a member of the Hawaiian Band, who died some ten years ago, at the ago of 40 years.

Chorus:

Maikai ke aloha a ka ipo--

Hana mao ole i ka puuwai,

Houhou liilii i ka poli--

Nowelo i ka pili aoao.

2. A mau ka pili’na olu pono;

Huli a’e, hooheno malie,

Hanu liilii nahenahe,

Nowelo i ka pili aoao.

Chorus.

The author of the mele was a Hawaiian named John Meha, who died some years ago. He was for many years a member of the Hawaiian Band and set the words to the music given below, which has since been arranged by Captain Berger.

[Translation]

Side by side

Chorus:

Most dear to the soul is a love-touch;

Its pulse stirs ever the heart

And gently throbs iii the breast--

At thrill from the touch of the side.

2. In time awakes a new charm

As you turn and gently caress;

Short comes to breath--at

The thrill from the touch of the side.

Chorus.

The fragments of Hawaiian music that have drifted down to us no doubt remain true to the ancient type, however much they may have changed in quality. They show the characteristics that stamp all primitive music--plaintiveness to the degree almost of sadness, monotony, lack of acquaintance with the full range of intervals that make up our diatonic scale, and therefore a measurable absence of that ear-charm we call melody. These are among its deficiencies.

If, on the other hand, we set down the positive qualities by the possession of which it makes good its claim to be classed as music, we shall find that it has a firm hold on rhythm. This is indeed one of the special excellencies of Hawaiian music. Added to this, we find that it makes a limited use of such intervals as the third, fifth, fourth, and at the same time resorts extravagantly, as if in compensation, to a fine tone-carving that divides up the tone-interval into fractions so much less than the semitone that our ears are almost indifferent to them, and are at first inclined to deny their existence. This minute division of the tone, or step, and neglect at the same time of the broader harmonic intervals, reminds one of work in which the artist charges his picture with unimportant detail, while failing in attention to the strong outlines. Among its merits we must not forget to mention a certain quality of tone-color which inheres in the Hawaiian tongue and which greatly tends to the enhancement of Hawaiian music, especially when thrown into rhythmic forms.

The first thing, then, to repeat, that will strike the auditor on listening to this primitive music will be its lack of melody. The voice goes wavering and lilting along like a canoe on a rippling ocean.

Click to enlarge

PLATE XVIII

HALA FRUIT BUNCH AND DRUPE WITH A ''LEI''

(PANDANUS ODORATISSIMUS)

[paragraph continues] Then, of a sudden, it swells upward, as if lifted by some wave of emotion; and there for a time it travels with the same fluctuating movement, soon descending to its old monotone, until again moved to rise on the breast of some fresh impulse. The intervals sounded may be, as already said, a third, or a fifth, or a fourth; but the whole movement leads nowhere; it is an unfinished sentence. Yet, in spite of all these drawbacks and of this childish immaturity, the amateur and enthusiast finds himself charmed and held as if in the clutch of some Old-World spell, and this at what others will call the dreary and monotonous intoning of the savage.

In matters that concern the emotions it is rarely possible to trace with certainty the lines that lead up from effect to cause. Such is the nature of art. If we would touch the cause which lends attractiveness to Hawaiian music, we must look elsewhere than to melody. In the belief of the author the two elements that conspire for this end are rhythm and tone-color, which comes of a delicate feeling for vowel-values.

The hall-mark of Hawaiian music is rhythm, for the Hawaiians be-long to that class of people who can not move hand or foot or perform any action except they do it rhythmically. Not alone in poetry and music and the dance do we find this recurring accent of pleasure, but in every action of life it seems to enter as a timekeeper and regulator, whether it be the movement of a fingerful of poi to the mouth or the swing of a kahili through the incense-laden air at the burial of a chief.

The typical Hawaiian rhythm is a measure of four beats, varied at times by a 2-rhythm, or changed by syncopation into a 3-rhythm.

These people have an emotional susceptibility and a sympathy with environment that belongs to the artistic temperament; but their feelings, though easily stirred, are not persistent and ideally centered; they readily wander away from any example or pattern. In this way may be explained their inclination to lapse from their own standard of rhythm into inexplicable syncopations.

As an instance of sympathy with environment, an experience with a hula dancer may be mentioned. Wishing to observe the movement of the dance in time with the singing of the mele, the author asked him to perform the two at one time. He made the attempt, but failed. At length, bethinking himself, he drew off his coat and bound it about his loins after the fashion of a pa-ú, such as is worn by hula dancers. He at once caught inspiration, and was thus enabled to perform the double rule of dancer and singer.

It has been often remarked by musical teachers who have had experience with these islanders that as singers they are prone to flat the tone and to drag the time, yet under the stimulus of emotion they show the ability to acquit themselves in these respects with great credit. The native inertia of their being demands the spur of excitement

to keep them up to the mark. While human nature everywhere shares in this weakness, the tendency seems to be greater in the Hawaiian than in some other races of no higher intellectual and esthetic advancement.

Another quality of the Hawaiian character which reenforces this tendency is their spirit of communal sympathy. That is but another way of saying that they need the stimulus of the crowd, as well as of the occasion, even to make them keep step to the rhythm of their own music. In all of these points they are but an epitome of humanity.

Before closing this special subject, the treatment of which has grown to an unexpected length, the author feels constrained to add one more illustration of Hawaii's musical productions. The Hawaiian national hymn on its poetical side may be called the last appeal of royalty to the nation's feeling of race-pride. The music, though by a foreigner, is well suited to the words and is colored by the environment in which the composer has spent the best years of his life. The whole production seems well fitted to serve as the clarion of a people that need every help which art and imagination can offer.

Click to enlarge

PLATE XIX

PU (TRITON TRITONIS)

Click to enlarge

XIV--Hawaii Ponoi

Click to enlarge

XIV--Hawaii Ponoi

Click to enlarge

XIV--Hawaii Ponoi

HAWAI'I PONOI

Refrain:

Makua lani, e,

Kamehameha, e,

Na kaua e pale,

Me ka ihe.

2. Hawai’i ponoí,

Nana i na ’li’i,

Na kaua muli kou,

Na poki’i.

Refrain:

3. Hawai’i ponoí

E ka lahui, e,

O kau hana nui

E ui, e.

Refrain.

[Translation]

Hawaii Ponoi

Refrain:

Protector, heaven-sent,

Kamehameha great,

To vanquish every foe,

With conquering spear.

2. Men of Hawaii's land,

Look to your native chiefs,

Your sole surviving lords,

The nation's pride.

Refrain:

3. Men of Hawaiian stock,

My nation ever dear,

With loins begirt for work,

Strive with your might.

Refrain.

138:a The early American missionaries to Hawaii named the musical notes of the scale pa, ko, li, ha, no, la, mi.

139:a The author can see no reason for supposing that this prolonged utterance had anything to do with that Hindoo practice belonging to the yoga, the exercise of which consists in regulating the breath.

146:a The writer is indebted to Miss Elsner not only for the above comments but for the following score which she has cleverly arranged as a sample of nose-flute music produced by Keaonaloa.

149:a Italics used are those of the present author.

150:a These bamboos were, no doubt, the same as the kaékeéke, elsewhere described. (See p. 122.)

154:a The Evolution of Music from the Italian Standpoint, in the Century Library of Music, xvi, 521.

155:a Halau. The rainy valley of Hanalei, on Kauai, is here compared to a halau, a dance-hall, apparently because the rain-columns seem to draw together and inclose the valley within walls, while the dark foreshortened vault of heaven covers it as with a roof.

155:b Kumano. A water-source, or, as here, perhaps, a sort of dam or loose stone wall that was run out into a stream for the purpose of diverting a portion of it into a new channel.

155:c Like. A bud; fresh verdure; a word much used in modern Hawaiian poetry.

155:d Opiwai. A watershed. In Hawaii a knife-edged ridge as narrow as the back of a horse will often decide the course of a stream, turning its direction from one to the other side of the island.

155:e Waioli (wai, water; oli, joyful). The name given to a part of the valley of Hanalei, also the name of a river.

162:a Waipi’o. A deep valley on the windward side of Hawaii.

162:b Paka’alana. A temple and the residence of King Liloa in Waipi’o.

162:c Paepae. The doorsill (of this temple), always an object of superstitious regard, but especially so in the case of this temple. Here it stands for the whole temple.

162:d Liloa. A famous king of Hawaii who had his seat in Waipi’o.

162:e Wahine pii ka pali. Haina-kolo, a mythical character. is probably the one alluded to. She married a king of Kukulu o Kahiki, and. being deserted by him, swam back to Hawaii. Arrived at Waipi’o in a famishing state, she climbed the heights and ate of the ulei berries without first propitiating the local deity with a sacrifice. As an infliction of the offended deity, she became distraught and wandered away into the wilderness. Her husband repented of his neglect and after long search found her. Under kind treatment she regained her reason and the family was happily reunited.

162:f Lau laau. Leaves of plants.

162:g Hoolaau. The last part of this word, laau, taken in connection with the last word of the previous verse, form a capital instance of word repetition. This was an artifice much used in Hawaiian poetry, both as a means of imparting tone-color and for the punning wit it was supposed to exhibit.

162:h Ua pe’e pa Kai-a-ulu a Waimea. Kai-a-ulu is a fierce rain-squall such as arises suddenly in the uplands of Waimea, Hawaii. The traveler, to protect himself, crouches (pe’e) behind a hummock of grass, or builds up in all haste a barricade (pa) of light stuff as a partial shelter against the oncoming storm.

162:i Kai. Taken in connection with Kai-a-ulu in the preceding verse, this is another instance of verse repetition. This word, the primary meaning of which is sea, or ocean, is used figuratively to represent a source of comfort or life.

162:j Keoloewa. The name of one of the old gods belonging to the class called akua noho, a class of deities that were sent by the necromancers on errands of demoniacal possession.

167:a Papi’o-huli. A slope in the western valley-side at the head of Nuuanu, where the tall grass (kawelu) waves (holu) in the wind.