Click to enlarge

ELDER FREDERICK W EVANS.

The Communistic Societies of the United States, by Charles Nordhoff, [1875], at sacred-texts.com

It was on a bleak and sleety December day that I made my first visit to a Shaker family. As I came by appointment, a brother, whom I later found to be the second elder of the family, received me at the door, opening it silently at the precise moment when I had reached the vestibule, and, silently bowing, took my bag from my hand and motioned me to follow him. We passed through a hall in which I saw numerous bonnets, cloaks, and shawls hung up on pegs, and passed an empty dining-hall, and out of a door into the back yard, crossing which we entered another house, and, opening a door, my guide welcomed me to the "visitors' room." "This," said he, "is where you will stay. A brother will come in presently to speak with you." And with a bow my guide noiselessly slipped out, softly closed the door behind him, and I was alone.

I found myself in a comfortable low-ceiled room, warmed by an air-tight stove, and furnished with a cot-bed, half a dozen chairs, a large wooden spittoon filled with saw-dust, a looking-glass, and a table. The floor was covered with strips of rag carpet, very neat and of a pretty, quiet color, loosely laid down. Against the wall, near the stove, hung a dust-pan, shovel, dusting-brush, and small broom. A door opened into an inner room, which contained another bed and conveniences for washing. A closet in the wall held matches, soap, and other articles. Every thing was scrupulously neat and clean. On the table were laid a number of Shaker books and newspapers.

[paragraph continues] In one corner of the room was a bell, used, as I afterward discovered, to summon the visitor to his meals. As I looked out of a window, I perceived that the sash was fitted with screws, by means of which the windows could be so secured as not to rattle in stormy weather; while the lower sash of one window was raised three or four inches, and a strip of neatly fitting plank was inserted in the opening—this allowed ventilation between the upper and lower sashes, thus preventing a direct draught, while securing fresh air.

I was still admiring these ingenious little contrivances, when, with a preliminary knock, entered to me a tall, slender young man, who, hanging his broad-brimmed hat on a peg, announced himself to me as the brother who was to care for me during my stay. He was a Swede, a student of the university in his own country, and a person of intelligence, some literary culture, and I should think of good family. His attention had been attracted to the Shakers by Mr. Dixon's book, "The New America;" he had come over to examine the organization, and had found it so much to his liking that, coming as a visitor, he had remained as a member. He had been here six or seven years. He had a fresh, fine complexion, as most of the Shaker men and women have—particularly the latter; his hair was cut in the Shaker fashion, straight across the forehead, and suffered to grow long behind, and he wore the long, blue-gray coat, a collar without a neck-tie, and the broad-brimmed whitish-gray felt hat of the order. His voice was soft and low, his motions noiseless, his conversation in a subdued tone, his smile ready; but his expression was that of one who guarded himself against the world, with which he was determined to have nothing to do. Frank and communicative he was, too, though I do not doubt that my tireless questioning sometimes bored him. Such as I have described him I have found all or nearly all the Shaker people—polite, patient, noiseless in their motions except during their "meetings" or worship, when they are

Click to enlarge

ELDER FREDERICK W EVANS.

sometimes quite noisy; scrupulously neat, and much given to attend to their own business.

The Sabbath quiet and stillness which prevailed I attributed to the fact that there had been a death in the family, and the funeral was to be held that morning; but I discovered afterwards that an eternal Sabbath stillness reigns in a Shaker family—there being no noise or confusion, or hum of busy industry at any time, although they are a most industrious people.

While the Swedish brother was, in answer to my questions, giving me some account of himself, to us came Elder Frederick, the head of the North or Gathering Family at Mount Lebanon, and the most noted of all the Shakers, because he, oftener than any other, has been sent out into the world to make known the society's doctrines and practice.

Frederick W. Evans is an Englishman by birth, and was a "reformer" in the old times, when men in this country strove for "land reform," the rights of labor, and against the United States Bank and other monopolies of forty or fifty years ago. He is now sixty-six years of age, but looks not more than fifty; was brought to this country at the age of twelve; became a socialist in early life, and, after trying life in several communities which perished early, at last visited the Shakers at Mount Lebanon, and after some months of trial and examination, joined the community, and has remained in it ever since—about forty-five years.

He is both a writer and a speaker; and while not college bred, has studied and read a good deal, and has such natural abilities as make him a leader among his people, and a man of force any where. He is a person of enthusiastic and aggressive temperament, but with a practical and logical side to his mind, and with a hobby for science as applied to health, comfort, and the prolongation of life. In person he is tall, with a stoop as though he had overgrown his strength in early life;

with brown eyes, a long nose, a kindly, serious face, and an attractive manner. He was dressed rigidly in the Shaker costume.

Click to enlarge

VIEW OF A SHAKER VILLAGE.

Mount Lebanon lies beautifully among the hills of Berkshire, two and a half miles from Lebanon Springs, and seven miles from Pittsfield. The settlement is admirably placed on the hillside to which it clings, securing it good drainage, abundant water, sunshine, and the easy command of water-power. Whoever selected the spot had an excellent eye for beauty and utility in a country site. The views are lovely, broad, and varied; the air is pure and bracing; and, in short, a company of people desiring to seclude themselves from the world could hardly have chosen a more delightful spot.

As you drive up the road from Lebanon Springs, the first building belonging to the Shaker settlement which meets your eye is the enormous barn of the North Family, said to be the largest in the three or four states which near here come together, as in its interior arrangements it is one of the most

complete. This huge structure lies on a hillside, and is two hundred and ninety-six feet long by fifty wide, and five stories high, the upper story being on a level with the main road, and the lower opening on the fields behind it. Next to this lies the sisters' shop, three stories high, used for the women's industries; and next, on the same level, the family house, one hundred feet by forty, and five stories high. Behind these buildings, which all lie directly on the main road, is another set—an additional dwelling-house, in which are the visitors' room and several rooms where applicants for admission remain while they are on trial; near this an enormous woodshed, three stories high; below a carriage-house, wagon sheds, the brothers' shop, where different industries are carried on, such as broom-making and putting up garden seeds; and farther on, the laundry, a saw-mill and grist-mill and other machinery, and a granary, with rooms for hired men over it. The whole establishment is built on a tolerably steep hillside.

Click to enlarge

THE HERB HOUSE, MOUNT LEBANON.

A quarter of a mile farther on are the buildings of the Church Family, and also the great boiler-roofed church of the society; and other communes or families are scattered along, each having all its interests separate, and forming a distinct

community, with industries of its own, and a complete organization for itself.

Click to enlarge

MEETING HOUSE AT MOUNT LEBANON.

The illustrations show sufficiently the character of the different buildings and the style of architecture, and make more detailed description needless. It need only be said that whereas on Mount Lebanon they build altogether of wood, in other settlements they use also brick and stone. But the peculiar nature of their social arrangements leads them to build very large houses.

Elder Frederick came to give me notice that I was permitted to witness the funeral ceremonies of the departed sister, which were set for ten o'clock, in the assembly-room; and thither I was accordingly conducted at the proper time by one of the brethren. The members came into the room rapidly, and ranged themselves in ranks, the men and women on opposite sides of the room, and facing each other. All stood up, there being no seats. A brief address by Elder Frederick opened the services,

Click to enlarge

INTERIOR OF MEETING-HOUSE AT MOUNT LEBANON.

after which there was singing; different brethren and sisters spoke briefly; a call was made to the spirit of the departed to communicate, and in the course of the meeting a medium delivered some words supposed to be from this source; some memorial verses were read by one of the sisters; and then the congregation separated, after notice had been given that the body of the dead sister would be placed in the hall, where all could take a last look at her face. I, too, was asked to look; the good brother who conducted me to the plain, unpainted pine coffin remarking very sensibly that "the body is not of much importance after it is dead."

Afterwards, in conversation, Elder Frederick told me that the "spiritual" manifestations were known among the Shakers many years before Kate Fox was born; that they had had all manner of manifestations, but chiefly visions and communications through mediums; that they fell, in his mind, into three epochs: in the first the spirits laboring to convince unbelievers in the society; in the second proving the community, the spirits relating to each member his past history, and showing up, in certain cases, the insincerity of professions; in the third, he said, the Shakers reacted on the spirit world, and formed communities of Shakers there, under the instruction of living

[paragraph continues] Shakers. "There are at this time," said he, "many thousands of Shakers in the spirit world." He added that the mediums in the society had given much trouble because they imagined themselves reformers, whereas they were only the mouth-pieces of spirits, and oftenest themselves of a low order of mind. They had to teach the mediums much, after the spirits ceased to use them.

In what follows I give the substance, and often the words, of many conversations with Elder Frederick and with several of the brethren, relating to details of management and to doctrinal points and opinions, needed to fill up the sketch given in the two previous chapters.

As to new members, Elder Frederick said the societies had not in recent years increased—some had decreased in numbers. But they expected large accessions in the course of the next few years, having prophecies among themselves to that effect. Religious revivals he regarded as "the hot-beds of Shakerism;" they always gain members after a "revival" in any part of the country. "Our proper dependence for increase is on the spirit and gift of God working outside. Hence we are friendly to all religious people."

They had changed their policy in regard to taking children, for experience had proved that when these grew up they were oftenest discontented, anxious to gain property for themselves, curious to see the world, and therefore left the society. For these reasons they now almost always decline to take children, though there are some in every society; and for these they have schools—a boys’ school in the winter and a girls’ school in summer-teaching all a trade as they grow up. "When men or women come to us at the age of twenty-one or twenty-two, then they make the best Shakers. The society then gets the man's or woman's best energies, and experience shows us that they have then had enough of the world to satisfy their curiosity and make them restful. Of course we like to keep up our numbers;

but of course we do not sacrifice our principles. You will be surprised to know that we lost most seriously during the war. A great many of our younger people went into the army; many who fought through the war have since applied to come back to us; and where they seem to have the proper spirit, we take them. We have some applications of this kind now."

A great many Revolutionary soldiers joined the societies in their early history; these did not draw their pensions; most of them lived to be old, and "I proved to Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Stanton once, when we were threatened with a draft," said Elder Frederick, "that our members had thus omitted to draw from the government over half a million of dollars due as pensions for army service."

With their management, he said, they had not much difficulty in sloughing off persons who come with bad or low motives; and in this I should say he was right; for the life is strictly ascetic, and has no charms for the idler or for merely sentimental or romantic people. "If one comes with low motives, he will not be comfortable with us, and will presently go away; if he is sincere, he may yet be here a year or two before he finds himself in his right place; but if he has the true vocation he will gradually work in with us."

He thought an order of celibates ought to exist in every Protestant community, and that its members should be self-supporting, and not beggars; that the necessities and conscience of many in every civilized community would be relieved if there were such an order open to them.

In admitting members, no property qualification is made; and in practice those who come in singly, from time to time, hardly ever possess any thing; but after a great revival of religion, when numbers come in, usually about half bring in more or less property, and often large amounts.

As to celibacy, he asserted in the most positive manner that it is healthful, and tends to prolong life; "as we are constantly

proving." He afterward gave me a file of the Shaker, a monthly paper, in which the deaths in all the societies are recorded; and I judge from its reports that the death rate is low, and the people mostly long-lived. *

"We look for a testimony against disease," he said; "and even now I hold that no man who lives as we do has a right to be ill before he is sixty; if he suffer from disease before that, he is in fault. My life has been devoted to introducing among our people a knowledge of true physiological laws; and this knowledge is spreading among all our societies. We are not all perfect yet in these respects; but we grow. Formerly fevers were prevalent in our houses, but now we scarcely ever have a case; and the cholera has never yet touched a Shaker village."

"The joys of the celibate life are far greater than I can make you know. They are indescribable."

The Church Family at Mount Lebanon, by the way, have built and fitted up a commodious hospital, for the permanently disabled of the society there. It is empty, but ready; and "better empty than full," said an aged member to me.

Among the members they have people who were formerly clergymen, lawyers, doctors, farmers, students, mechanics, sea-captains, soldiers, and merchants; preachers are in a much larger proportion than any of the other professions or callings. They get members from all the religious denominations except the Roman Catholic; they have even Jews. Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, and Adventists furnish them the greatest proportion. They have always received colored people, and have some in several of the societies.

"Every commune, to prosper, must be founded, so far as

its industry goes, on agriculture. Only the simple labors and manners of a farming people can hold a community together. Wherever we have departed from this rule to go into manufacturing, we have blundered." For his part, he would like to make a law for the whole country, that every man should own a piece of land and work on it. Moreover, a community, he said, should, as far as possible, make or produce all it uses. "We used to have more looms than now, but cloth is sold so cheaply that we gradually began to buy. It is a mistake; we buy more cheaply than we can make, but our home-made cloth is much better than that we can buy; and we have now to make three pairs of trousers, for instance, where before we made one. Thus our little looms would even now be more profitable—to say nothing of the independence we secure in working them."

In the beginning, he said, the societies were desirous to own land; and he thought

|

it, and thereupon it was dropped; but since then the society had come generally to favor a law limiting the quantity of land which any citizen should own to not more than one hundred acres.

Click to enlarge

SHAKER OFFICE AND STORE AT MOUNT LEBANON.

He thought it a mistake in his people to own farms outside of their family limits, as now they often do. This necessitates the employment of persons not members, and this he thought impolitic. "If every out-farm were sold, the society would be better off. They are of no real advantage to us, and I believe of no pecuniary advantage either. They give us a prosperous look, because we improve them well, and they do return usually a fair percentage upon the investment; but, on the other hand, this success depends upon the assiduous labor of some of our ablest men, whose services would have been worth more at home. We ought to get on without the use of outside labor. Then we should be confined to such enterprises as are best for us. Moreover we ought not to make money. We ought to make no more than a moderate surplus over our usual living,

so as to lay by something for hard times. In fact, we do not do much more than this."

Nevertheless nearly all the Shaker societies have the reputation of being wealthy.

In their daily lives many profess to have attained perfection: these are the older people. I judge by the words I have heard in their meetings that the younger members have occasion to wish for improvement, and do discover faults in themselves. One of the older Shakers, a man of seventy-two years, and of more than the average intelligence, said to me, in answer to a direct question, that he had for years lived a sinless life. "I say to any who know me, as Jesus said to the Pharisees, 'which of you convicteth me of sin.'" Where faults are committed, it is held to be the duty of the offender to confess to the elder, or, if it is a woman, to the eldress; and it is for these, too, to administer reproof. "For instance, suppose one of the members to possess a hasty temper, not yet under proper curb; suppose he or she breaks out into violent words or impatience, in a shop or elsewhere; the rest ought to and do tell the elder, who will thereupon administer reproof. But also the offending member ought not to come to meeting before having made confession of his sin to the elder, and asked pardon of those who were the subjects and witnesses of the offense."

As to books and literature in general, they are not a reading people. "Though a man should gain all the natural knowledge in the universe, he could not thereby gain either the knowledge or power of salvation from sin, nor redemption from a sinful nature." * Elder Frederick's library is of extremely limited range, and contains but a few books, mostly concerning social problems and physiological laws. The Swedish brother, who had been a student, said in answer to my

question, that it did not take him long to wean himself from the habit of books; and that now, when he felt a temptation in that direction, he knew he must examine himself, because he felt there was something wrong about him, dragging him down from his higher spiritual estate. He did not regret his books at all. An intelligent, thoughtful old Scotchman said on the same subject that he, while still of the world, had had a hobby for chemical research, to which he would probably have devoted his life; that he still read much of the newest investigations, but that he had found it better to turn his attention to higher matters; and to bring the faculties which led him naturally toward chemical studies to the examination of social problems, and to use his knowledge for the benefit of the society.

The same old Scotchman, now seventy-three years old, and a cheery old fellow, who had known the elder Owen, and has lived as a Shaker forty years, I asked, "Well, on the whole, reviewing your life, do you think it a success?" He replied, clearly with the utmost sincerity: "Certainly; I have been living out the highest aspirations my mind was capable of. The best I knew has been realized for and around me here. With my ideas of society I should have been unfit for any thing in the world, and unhappy because every thing around me would have worked contrary to my belief in the right and the best. Here I found my place and my work, and have been happy and content, seeing the realization of the highest I had dreamed of."

Considering the homeliness of the buildings, which mostly have the appearance of mere factories or human hives, I asked Elder Frederick whether, if they were to build anew, they would not aim at some architectural effect, some beauty of design. He replied with great positiveness, "No, the beautiful, as you call it, is absurd and abnormal. It has no business with us. The divine man has no right to waste money upon what you

would call beauty, in his house or his daily life, while there are people living in misery." In building anew, he would take care to have more light,

|

They have paid much attention to the early Jewish policy in Palestine, and the laws concerning the distribution of land, the Sabbatical year, service, and the collection of debts, are praised by them as establishing a far better order of things for the world in general than that which obtains in the civilized world to-day.

They hold strongly to the equality of women with men, and look forward to the day when women shall, in the outer world

as in their own societies, hold office as well as men. "Here we find the women just as able as men in all business affairs, and far more spiritual." "Suppose a woman wanted, in your family, to be a blacksmith, would you consent?" I asked; and he replied, "No, because this would bring men and women into relations which we do not think wise." In fact, while they call men and women equally to the rulership, they very sensibly hold that in general life the woman's work is in the house, the man's out of doors; and there is no offer to confuse the two.

Moreover, being celibates, they use proper precautions in the intercourse of the sexes. Thus Shaker men and women do not shake hands with each other; their lives have almost no privacy, even to the elders, of whom two always room together; the sexes even eat apart; they labor apart; they worship, standing and marching, apart; they visit each other only at stated intervals and according to a prescribed order; and in all things the sexes maintain a certain distance and reserve toward each other. "We have no scandal, no tea-parties, no gossip."

Moreover, they mortify the body by early rising and by very plain living. Few, as I said before, eat meat; and I was assured that a complete and long-continued experience had proved to them that young people maintain their health and strength fully without meat. They wear a very plain and simple dress, without ornament of any kind; and the costume of the women does not increase their attractiveness, and makes it difficult to distinguish between youth and age. They keep no pet animals, except cats, which are maintained to destroy rats and mice. They have, of course, none of the usual relations to children—and the boys and girls whom they take in are in each family put under charge of a special "care-taker," and live in separate houses, each sex by itself.

Smoking tobacco is by general consent strictly prohibited. A few chew tobacco, but this is thought a weakness, to be

Click to enlarge

A GROUP OF SHAKER CHILDREN.

Click to enlarge

SHAKER DINING HALL.

left off as standing in the way of a perfect life.

The following notice in the Shaker shows that even some very old sinners in this respect reform:

OBITUARY.

On Tuesday, Feb. 20th, 1873, Died, by the power of truth, and for the cause of Human Redemption, at the Young Believers' Order, Mt. Lebanon, in the following much-beloved Brethren, the

TOBACCO-CHEWING HABIT,

|

aged respectively, |

|

|

|

In D.S. |

51 |

years’ duration. |

|

In C.M. |

57 |

“ |

|

In A.G. |

15 |

“ |

|

In T.S. |

36 |

“ |

|

In OLIVER PRENTISS |

71 |

“ |

|

In L.S. |

45 |

“ |

|

In H.C. |

53 |

“ |

|

In O.K. |

12 |

“ |

No funeral ceremonies, no mourners, no grave-yard; but an honorable RECORD thereof made in the Court above. Ed.

Reviewing all these details, it did not surprise me when Elder Frederick remarked, "Every body is not called to the divine life." To a man or woman not thoroughly and earnestly in love with an ascetic life and deeply disgusted with the world, Shakerism would be unendurable; and I believe insincerity to be rare among them. It is not a comfortable place for hypocrites or pretenders.

The housekeeping of a Shaker family is very thoroughly and effectively done. The North Family at Mount Lebanon consists of sixty persons; six sisters suffice to do the cooking and baking, and to manage the dining-hall; six other sisters in half a day do the washing of the whole family. The deaconesses give out the supplies. The men milk in bad weather, the women when it is warm. The Swedish brother told me that he was this winter taking a turn at milking—to mortify the flesh, I imagine, for he had never done this in his own home; and he used neither milk nor butter. Many of the

brethren have not tasted meat in from twenty-five to thirty-five years. Tea and coffee are used, but very moderately.

There is no servant class.

"In a community, it is necessary that some one person shall always know where every body is," and it is the elder's office to have this knowledge; thus if one does not attend a meeting, he tells the elder the reason why.

Obedience to superiors is an important part of the life of the order.

Living as they do in large families compactly stowed, they have become very careful against fires, and "a real Shaker always, when he has gone out of a room, returns and takes a look around to see that all is right."

The floor of the assembly room was astonishingly bright and clean, so that I imagined it had been recently laid. It had, in fact, been used twenty-nine years; and in that time had been but twice scrubbed with water. But it was swept and polished daily; and the brethren wear to the meetings shoes made particularly for those occasions, which are without nails or pegs in the soles, and of soft leather. They have invented many such tricks of housekeeping, and I could see that they acted just as a parcel of old bachelors and old maids would, any where else, in these particulars—setting much store by personal comfort, neatness, and order; and no doubt thinking much of such minor morals. For instance, on the opposite page is a copy of verses which I found in the visitors' room in one of the Shaker families—a silent but sufficient hint to the careless and wasteful.

Like the old monasteries, they are the prey of beggars, who always receive a dole of food, and often money enough to pay for a night's lodging in the neighboring village; for they do not like to take in strangers.

The visiting which is done on Sunday evenings is perhaps as curious as any part of their ceremonial. Like all else in

TABLE MONITOR. | |

GATHER UP THE FRAGMENTS THAT REMAIN, THAT NOTHING BE LOST.—CHRIST. | |

|

Here then is the pattern We wish to speak plainly What we deem good order, We find of those bounties

|

Tho' Heaven has bless'd us We often find left, Now if any virtue Let none be offended

|

|

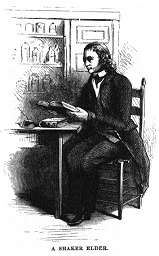

[VISITORS’ EATING ROOM, SHAKER VILLAGE.] | |

their lives, these visits are prearranged for them—a certain group of sisters visiting a certain group of brethren. The sisters, from four to eight in number, sit in a row on one side, in straight-backed chairs, each with her neat hood or cap, and each with a clean white handkerchief spread stiffly across her lap. The brethren, of equal number, sit opposite them, in another row, also in stiff-backed chairs, and also each with a white handkerchief smoothly laid over his knees. Thus arranged, they converse upon the news of the week, events in the outer world, the farm operations, and the weather; they sing, and in general have a pleasant reunion, not without gentle laughter and mild amusement. They meet at an appointed time, and at another set hour they part; and no doubt they find great satisfaction in this—the only meeting in which they fall into sets which do not include the whole family.

Since these chapters were written, Hervey Elkins's pamphlet, "Fifteen Years in the Senior Order of the Shakers," printed at Hanover, New Hampshire, in 1853, has come into my hands. Elkins gives some details out of his own experience of Shaker life which I believe to be generally correct, and which I quote here, as filling up some parts of the picture I have tried to give of the Shaker polity and life:

"The spiritual orders, laws, and statutes, never to be revoked, are in substance as follows: None are admitted within the walls of Zion, as they denominate their religious sphere, but by a confession to one or more incarnate witnesses of every debasing and immoral act perpetrated by the confessor within his remembrance; also every act which, though the laws of men may sanction, may be deemed sinful in the view of that new and sublimer divinity which he has adopted. The time, the place, the motive which produced and pervaded the act, the circumstances which aggravated the case, are all to be disclosed. No stone is to be left unturned—no filth is suffered to remain. The temple of God, or the soul, must be carefully swept and garnished, before the new man can enter it and there make his abode. (Christ, or the Divine Intelligence which emanated from God the Father, transforms the soul into the new man spoken of in the Scriptures.)

"Those who have committed deeds cognizable by the laws of the land, shall never be admitted, until those laws have dealt with their transgressions and acquitted them.

"Those who have in any way morally wronged a fellow-creature, shall make restitution to the satisfaction of the person injured.

"Wives who have unbelieving husbands must not be admitted without their husbands' consent, or until they are lawfully released from the marriage contract, and vice versa. They may confess their sins, but cannot enter the sacred compact.

"All children admitted shall be bound by legal indentures, and shall, if refractory, be returned to their parents.

"There shall exist three Orders, or degrees of progression, viz.: The Novitiate, the Junior, and the Senior.

"All adults may enter the Novitiate Order, and then may progress to a higher, by faithfulness in supporting the Gospel requirements.

"When at the age of twenty-one, the Church Covenant is presented to all the young members to peruse, and to deliberate and decide whether or not they will maintain the conditions therein expressed. To older members it is presented after all legal embarrassments upon their estates are settled, and they desire to be admitted to full fellowship with those who have consecrated all. And whoever, after having escaped the servility of Egypt, shall again desire its taskmasters and flesh-pots, are unfit for the kingdom of God; and in case of secession or apostasy shall, by their own deliberate and matured act (that of placing their signatures and seals upon this instrument when in the full possession of all their mental powers), be debarred from legally demanding any compensation whatever for the property or services which they had dedicated to a holy purpose.

"This instrument is legally and skillfully formed, and none are permitted to sign it until they have counted well the cost; or, at least, pondered for a time upon its requirements.

"Members also stipulate themselves by this signature to yield implicit obedience to the ministry, elders, deacons, and trustees, each in their respective departments of authority and duty.

"The Shaker government, in many points, resembles that of the military. All shall look for counsel and guidance to those immediately before them, and shall receive nothing from, nor make application for any thing to those but their immediate advisers. For instance: No elder in either of the subordinate bishoprics can make application for any amendment,

any innovation, any introduction of a new system, of however trivial a nature, to the ministry of the first bishopric; but he may desire and ask of his own ministry, and, if his proposal meet their concurrence, they will seek its sanction of those next higher. All are to regard their spiritual leaders as mediators between God and their own souls; and these links of divine communication, successively descending from Power and Wisdom, who constitute the dual God, to their Son and Daughter, Jesus and Ann, and from them to Ann's successors of the Zion of God on earth, down to the prattling infant who may have been gathered within this ark of safety—this concatenated system of spiritual delegation is the river of life, whose salutary waters flow through the celestial sphere for the cleansing and redemption of souls.

"Great humility and simplicity of life is practiced by the first ministry—two of each sex—upon whom devolves the charge of subordinate bishoprics, besides that of their own immediate care, the societies of Niskeyuna and Mount Lebanon. They will not even (and this is good policy) allow themselves those expensive conveniences of life which are so common among the laity of their sect. But extreme neatness is the most prominent characteristic of both them and their subordinates. They speak much of the model enjoined by Jesus, that whosoever would be the greatest should be the servant of all.

"A simple song, of a beautiful tune, inculcating this spirit, is often sung in their assemblies. The words are these:

"It is common for the leaders to crowd down, by humiliation, and withdraw patronage and attention from those whom they intend to ultimately promote to an official station. That such may learn how it seems to be slighted and humiliated, and how to stand upon their own basis, work spiritually for their own food without being dandled upon the soft lap of affection, or fed with the milk designed for babes. That also they be not deceived by the phantoms of self-wisdom; and that they martyr not in themselves the meek spirit of the lowly Jesus. Thus, while holding one in contemplation for an office of care and trust, they first prove him—the cause unknown to himself—to see how much he can bear, without exploding by impatience or faltering under trial.

"Virtually for this purpose, but ostensibly for some other, have I known

many promising young people moved to a back order, or lower grade of fellowship. By such trials the leaders think to try their souls in the furnace of affliction, withdraw them from earthly attachments, and imbue them with reliance upon God. In fact, to destroy terrestrial idols of every kind, to dispel the clouds of inordinate affection and concentrative love, which fascinatingly float around the mind and screen from its view the radiant brightness of heaven and heavenly things, is the great object of Shakerism.

"Whoever yields enough to the evil tempter to gratify in the least the sensual passions—either in deed, word, or thought—shall confess honestly the same to his elders ere the sun of another day shall set to announce a day of condemnation and wrath against the guilty soul. These vile passions are—fleshly lusts in every form, idolatry, selfishness, envy, wrath, malice, evil-speaking, and their kindred evils.

"The Sabbath shall be kept pure and holy to that degree that no books shall be read on that day which originated among the world's people, save those scientific books which treat of propriety of diction. No idle or vain stories shall be rehearsed, no unnecessary labor shall be performed—not even the cooking of food, the ablution of the body, the cutting of the hair, beard, or nails, the blacking and polishing of shoes or boots. All these things must be performed on Saturday, or postponed till the subsequent week. All fruit, eaten upon the Sabbath, must be earned to the dwelling-house on Saturday. But the dormitories may be arranged, the cows milked, all domestic animals fed, and food and drink warmed on Sunday. No one is allowed to go to his workshop, to walk in the gardens, the orchards, or on the farms, unless immediate duty requires; and those who of necessity go to their workshops, shall not tarry over fifteen minutes but by the direct liberty of the elders. The dwelling-house is the place for all to spend the Sabbath; and thither all concentrate—elders, deacons, brethren, and sisters. If any property is likely to incur loss—as hay and grain that is cut and remaining in the field, and is liable to be wet before Monday, it may be secured upon the Sabbath.

"All shall rise simultaneously every morning at the signal of the bell, and those of each room shall kneel together in silent prayer, strip from the beds the coverlets and blankets, lighten the feathers, open the windows to ventilate the rooms, and repair to their places of vocation. Fifteen minutes are allowed for all to leave their sleeping apartments. In the summer the signal for rising is heard at half-past four, in the winter

at half-past five. Breakfast is invariably one and a half hours after rising—in the summer at six, in the winter at seven; dinner always at twelve; supper at six. These rules are, however, slightly modified upon the Sabbath. They rise and breakfast on this day half an hour later, dine lightly at twelve, and sup at four. Every order maintains the same regularity in regard to their meals.

"In the Senior Order, at the ringing of a large bell, ten minutes before meal-time, all may gather into the saloons, and retire the ten minutes before the dining-hall alarm summons them to the table. All enter four doors and gently arrange themselves at their respective places at the table, then all simultaneously kneel in silent thanks for nearly a minute, then rise and seat themselves almost inaudibly at the table. No talking, laughing, whispering, or blinking are allowed while thus partaking of God's blessings. After eating, all rise together at the signal of the first elder, kneel as before, and gently retire to their places of vocation, without stopping in the dining-hall, loitering in the corridors and vestibules, or lounging upon the balustrades, doorways, and stairs.

"The tables are long, three feet in width, highly polished, without cloth, and furnished with white ware and no tumblers. The interdict which excludes glass-ware from the table must be attributed to conservatism rather than parsimony, for in most useful improvements the Shakers strive to excel. They tremble at adopting the customs of the world. At the tables, each four have all the varieties of food served for themselves, which precludes the necessity of continual passing and reaching.

"At half-past seven P.M. in the summer, and at eight in the winter, the large bell summons all of every order to their respective dwellings, there to retire, each individual in his own room, half an hour before evening worship. To retire is for the inmates of every room—generally from four to eight individuals—to dispose themselves in either one or two ranks, and sit erect, with their hands folded upon their laps, without leaning back or falling asleep; and in that position labor for a true sense of their privilege in the Zion of God—of the fact that God has prescribed a law which humbles and keeps them within the hollow of his hand, and has favored them with the blessing of worshiping him, with soul and body, unmolested, and according to the dictation of an enlightened mind and a tender and good conscience. If any chance to fall asleep while thus mentally employed, they may rise and bow four times, or gently shake, and then resume their seats.

"The man who is now the archbishop of Shakerism was, when a youth,

very apt to fall into a drowsy state in retiring time; but he broke up that habit by standing erect the half-hour before every meeting for six months. And there are many as zealous as he in supporting every order. No unnecessary walking in the corridors or passing in and out of doors are in this sacred time allowed. When the half-hour has expired, a small hand-bell summons all to the hall of worship. None are allowed to absent themselves without the elder's liberty. If any are unwell or tired, it is but a little matter to rap at the elder's door, or ask a companion to do it, where any one may receive liberty to retire to rest if it is expedient. All pass the stairs and corridors, and enter the hall, two abreast, upon tiptoe, bowing once as they enter, and pass directly to their place in the forming ranks.

"The house, of course, is vacated through the day, except by sisters, who take turns in cooking, making beds, and sweeping. When brethren and sisters enter, they must uncover their heads, and hang their hats and bonnets in the lower corridors, and walk softly, and open and shut doors gently, and in the fear of God. None are allowed to carry money into sacred worship. In a word, the sanctuary and the whole house shall be kept sacred and holy unto the Lord; and all shall spend the time allotted to be in the house mostly in their own rooms. Three evenings in the week are set apart for worship, and three for 'union meetings.' Monday evenings all may retire to rest at the usual meeting time, an hour earlier than usual. For the union meetings the brethren remain in their rooms, and the sisters, six, eight, or ten in number, enter and sit in a rank opposite to that of the brethren's, and converse simply, often facetiously, but rarely profoundly. In fact, to say 'agreeable things about nothing,' when conversant with the other sex, is as common there as elsewhere. And what of dignity or meaning could be said? where talking of sacred subjects is not allowed, under the pretext that it scatters those blessings which should be carefully treasured up; and bestowing much information concerning the secular plans of economy practiced by your own to the other sex is not approved; and where to talk of literary matters would be termed bombastic pedantry and small display, and would serve to exhibit accomplishments which might be enticingly dangerous. Nevertheless, an hour passes away very agreeably and even rapturously with those who there chance to meet with an especial favorite; succeeded soon, however, when soft words, and kind, concentrated looks become obvious to the jealous eye of a female espionage, by the agonies of a separation. For the tidings of such reciprocity, whether true or surmised,

is sure before the lapse of many hours to reach the ears of the elders; in which case, the one or the other party would be subsequently summoned to another circle of colloquy and union.

"No one is permitted to make mention of any thing said or done in any of these sittings to those who attend another, for party spirit and mischief might be the result. Twenty minutes of the union hour may be devoted to the singing of sacred songs, if desired.

"All are positively forbidden ever to say aught against their brother or their sister, whatever may be their defects; but such defects shall be made known to the elders, and to none else. 'If nothing good can be said of one, say nothing,' is a Shaker maxim. If one member is known by another to violate an ordinance of the Gospel, the witness thereto shall gently remind the transgressor, and request him to confess the deed to the elder. If he refuses, the witness shall divulge it; if he consents, then is the witness free, as having performed his duty.

"Brethren and sisters shall not visit each other's rooms unless for errands; and in such cases shall tarry no more than fifteen minutes. A sister shall not go to the brethren's work places unless accompanied by another. Brethren's and sister's workshops shall not be under one or the same roof; they shall not pass each other upon the stairs; nor one of each converse together unless a third person be present of more than ten years of age. They shall in no case give presents to each other, nor lend with the intention of never again receiving. If a sister desires any assistance, or desires any article made by the brethren, she must make application to the female deaconesses or stewards, and they will convey her wishes to the male stewards, who will provide the article or assistance requested. The converse is required of a brother; although it is more common for the brother to express his requests direct to the female steward, thus excluding one link of the concatenation. In each order a brother is generally appointed to aid the sisters in doing the heavy work of the laundry, dairy, kitchen, and similar places. All are required to spend their mornings and evenings, and their leisure time, in the performance of some good act.

"No one shall leave the premises of the family in which he lives without the consent of the elders; and he shall obtain the consent by stating the purpose or business which calls him away. This interdiction includes the act of going from one family to another. But on their own grounds brethren may range at pleasure; and the families are so large that the territory included in the domain of each extends in some directions for miles around.

"No conversation is allowed between members of different families, unless it be necessary, succinct, and discreet.

"Before a brother enters a sister's apartment, or a sister enters a brother's, they shall rap and enter by permission. When they enter the apartment of their own sex, they may open the door and ask, 'May I come in?'

"The name of a person shall never be used to designate a dumb beast. No one is allowed to play with or handle unnecessarily any beast whatever. Brethren and sisters may not unnecessarily touch each other. If a brother shakes hands with an unbelieving woman, or a sister with an unbelieving man, they shall make known the same to the elders before they attend worship. Such salutes are admissible, for the sake of civility or custom, if the world party first present the hand—never without. All visiting of the world's people, even their own relations, is forbidden, unless there exist a prospect of making converts, or of gathering some one into the fold. All visiting of other societies of their own sect is under the immediate superintendence of the ministry, who prescribe the number, select the persons, appoint the time, define the length of their stay, and the routes by which they may go and come.

"The deacons are empowered to change the employment of an individual for an hour, a day, or a week, to perform a necessary piece of labor. But a permanent removal to another vocation can be required only by the elders.

"No trading is to be done by any save the trustees, and those whom the trustees may license. No new literary work or new-fangled article can be admitted, unless it be first sanctioned by the ministry and elders. Trustees may purchase any thing they believe may be admissible, and present the same for the inspection of the leaders. If they disapprove it, it must be sold. The property is all legally held by trustees, who may at any time be removed by the ministry. The trustees are to supervise all financial transactions with the world and other families and societies of their own denomination, and do all by knowledge and union of the ministry and elders. There must be two trustees in every order, and they shall make their financial returns known to each other every journey they perform. An exact book account of every cent of disbursement and income shall be presented to the ministry at the close of every year. The deacons are also to keep an exact account of every thing manufactured or produced for sale in the family, and these two registers are compared by the ministry.

"Not a single action of life, whether spiritual or temporal, from the

initiative of confession, or cleansing the habitation of Christ, to that of dressing the right side first, stepping first with the right foot as you ascend a flight of stairs, folding the hands with the right-hand thumb and fingers above those of the left, kneeling and rising again with the right leg first, and harnessing first the right-hand beast, but that has a rule for its perfect and strict performance.

"The children, or all under the age of sixteen, unless very precocious, live, eat, work, play, sleep, and worship, accompanied only by their caretakers. Once upon the Sabbath do they worship with the adults. Their meetings are not so long, neither do they retire but fifteen minutes before them. They never attend union meetings until they emerge into the adult's degree. Stubborn children are sometimes corrected with a rod; but any child or beast that requires an extreme severity of coercion to induce them to conform, the society are not allowed to keep. The contumacious child must be returned to his parents or guardian, and the perverse beast must be sold.

"Prayer, supplication, persuasion, and keen admonition constitute the only means used to incline the disposition and bend the will of those arrived to years of understanding and reason."

* * * * * * * * * *

"The boys' shop, so called, is a building two stories in height. In the upper loft is a large room where the care-takers reside, and where the boys who wish to read, write, or reflect may retire from the jabbering and confusion below. Whenever they leave their house or shop, they are required to go two abreast and keep step with each other. No loud talking was allowable in the court-yards at any time. No talking or whispering when passing through the tasteful courts to their work, their school, their meetings, or their meals; a still, soft walk on tiptoe, and an indistinct closing of doors in the house; a gentle, yet a more brisk movement in the shops; a free and jovial conversation when by themselves in the fields; but not a word, unless when spoken to, when other brethren than their care-takers were present—such were the orders we saw rigorously enforced, and the lenities we freely granted. We allowed them to indulge in the innocent sports practiced elsewhere. But wrestling and scuffling were rarely permitted. No sports were allowed in the courtyards, unless all loud talk was suppressed. We a few times permitted them to roll trucks there, but allowed no verbal communication only by whispering.

"All were taught to confess all violations of their instructions, and a

portion of every Saturday was set apart for that purpose. They enter one at a time, and kneel before the care-taker; and, after confessing their faults, the care-taker makes some necessary inquiries in relation to other boys, gives them generally some good advice, and they depart. After eighteen years of age they are not required to kneel during the act of confession. To watch over a company of boys like these is, with a little tact, an easy task. The vigils must be incessant; but there are in so large a number those upon whom the care-taker may rely; and if ill conduct or bad habits are creeping in, it may soon be detected by a shrewd observer."

The contracting of a special liking between individuals of opposite sexes is in some of the societies called "sparking."

160:* In nine numbers of the Shaker (year 1873), twenty-seven deaths are recorded. Of these, Abigail Munson died at Mount Lebanon, aged 101 years, 11 months, and 12 days. The ages of the remainder were 97, 93, 88, 87, 86, 82, six above 75, four above 70, 69, 65, 64, 55, 54, 49, 37, 31, and two whose ages were not given.

163:* "Christ's First and Second Appearing"