The Syrian Goddess, by Lucian, tr. by Herbert A. Strong and John Garstang, [1913], at sacred-texts.com

The Syrian Goddess, by Lucian, tr. by Herbert A. Strong and John Garstang, [1913], at sacred-texts.com

THE dawn of history in all parts of Western Asia discloses the established worship of a nature-goddess in whom the productive powers of the earth were personified. 1 She is our Mother Earth, known otherwise as the Mother Goddess or Great Mother. Among the Babylonians 2 and northern Semites she was called Ishtar: she is the Ashtoreth of the Bible, and the Astarte of Phœnicia. In Syria her name was ‘Athar, and in Cilicia it had the form of ‘Ate (‘Atheh). At Hierapolis, with which we are primarily concerned, it appears in later Aramaic as Atargatis, a compound of the Syrian and Cilician forms. 3 In Asia Minor, where the influence of the Semitic language did not prevail, her various names have not survived, though it is recorded by a later Greek writer as "Ma" at one of her mountain shrines, and as Agdistis amongst one tribe of the Phrygians 4 and probably at Pessinus. These differences, however, are partly

questions of local tongue; for in one way and another there was still a prevailing similarity between the essential attributes and worship of the nature-goddess throughout Western Asia. 5

The "origins" of this worship and its ultimate development are not directly relevant to our present enquiry; but we must make passing allusion to a point of special interest and wide significance. As regards Asia Minor, at least, a theory that explains certain abnormal tendencies in worship and in legend would attribute to the goddess, in the primitive conception of her, the power of self-reproduction, complete in herself, a hypothesis justified by the analogy of beliefs current among certain states of primitive society. 6 However that may be, a male companion is none the less generally associated with her in mythology, even from the earliest historical vision of Ishtar in Babylonia, 7 where he was known as Tammuz. While evidence is wanting to define clearly the original position of this deity in relation to the goddess, 8 the general tendency of myth and legend in the lands of Syria and Asia Minor, with which we are

specially concerned, reveals him as her offspring, 9 the fruits of the earth. The basis of the myth was human experience of nature, particularly the death of plant life with the approach of winter and its revival with the spring. In one version accordingly "Adonis" descends for the six winter months to the underworld, until brought back to life through the divine influence of the goddess. The idea that the youth was the favoured lover of the goddess belongs to a different strain of thought, if indeed it was current in these lands at all in early times. In Asia Minor at any rate the sanctity of the goddess's traditional powers was safeguarded in popular legend by the emasculation of "Attis," and in worship by the actual emasculation of her priesthood, 10 perhaps the most striking feature of her cult. The abnormal and impassioned tendencies of her developed worship

would be derived, according to this theory, from the efforts of her worshippers to assist her to bring forth notwithstanding her singleness. However that may be, the mourning for the death of the youthful god, and rejoicing at his return, were invariable features of this worship of nature. It is reasonable to believe that long before the curtain of history was raised over Asia Minor the worship of this goddess and her son had become deep-rooted.

There then appeared the Hittites. In relation with Babylonia and Egypt, these peoples had already become known at the close of the third millennium B.C.; 11 and, to judge from the Biblical accounts, numbers of them had settled here and there throughout Syria and Palestine as early as the days of the patriarchs. 12 Nothing is known of their constitution and organization in these days, however; it is not until their own archives speak that we find them in the fourteenth century B.C. an already established constitutional power, with their capital at Boghaz-Keui. 13 Their sway extended southward into Syria as far as the Lebanon, eastward to the Euphrates, and at times into Mesopotamia, westward as far as Lydia, and probably to the sea coast. 14

Their chief deity was a God omnipotent, the "Lord of Heaven," 15 with lightning in his hand, the controller of storms ruling in the skies, and, hence identified with the sun. At Senjerli, in the north of

Click to enlarge

FIG. 1.—THE HITTITE

(See p. 6.)

[paragraph continues] Syria, he was represented simply with trident and hammer, 16 the emblems of the lightning and the

thunder. But a sculpture at Malâtia, on their eastern frontier, shows him standing on the back of a bull, the emblem of creative powers, 17 and bearing upon his shoulder a bow, identifying him with a God of Arms,

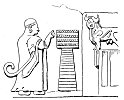

Click to enlarge

FIG. 2.—THE CHIEF HITTITE GOD AND GODDESS AT BOGHAZ-KEUI.

as was natural amongst warlike tribes, His enshrined image is found carved upon a rocky peak of the Kizil Dagh, 18 a ridge that rises from the southern

plains on the central plateau of Asia Minor. In the sanctuary near Boghaz-Keui, clad like their other deities in the Hittite warrior garb, he has assumed a conventional and majestic appearance, bearded, with the lightning emblem in one hand and his sceptre in the other, 19 a prototype of Zeus. The scene of which this sculpture is a part represents the ceremonial marriage of the god with the Great Mother, 20 with the rites and festivities that accompanied the celebration, so far as mural decoration permits of treatment of such a theme. From these sculptures we learn that which is fundamental in the Hittite

religion, namely, the recognition of a chief god and goddess, and though doubtless the outcome of the political conditions, the mating of these two deities at the proper season would seem to have been peculiarly natural and appropriate to the old established religion of the land. In this union, moreover, each god preserved its dignity and individuality, each cult maintained its proper ceremonies, yet the pair could be worshipped in common as the divine Father and Mother, the source of all life, human, animal, and vegetable.

With the goddess there is in these sculptures the image of the youth 21 who, in the original tradition, was her necessary companion, representing clearly, in this instance, her offspring, the fruits of the earth. 22 Indeed a later sculpture at Ivrîz seems to show this god, changed in form but still recognizable, 23 as the patron of agriculture, with bunches of grapes in one hand and ears of corn in the other. Even at Boghaz-Keui, this youthful deity is already accorded a smaller adjacent sanctuary, 24 devoted to his cult alone. Following the great deities are many

other figures, forming, as it were, two groups. Accompanying the god are the minor gods of the Hittite States, who, for the most part, are similar to himself in general appearance. 25 They are followed by priests and men who are taking part in the celebration, in which it would appear revelry and dancing

Click to enlarge

FIG. 3.—THE HITTITE BULL-GOD AT EYUK.

were not omitted. In the train of the goddess, who like her son stands upon the back of a lioness, there follow two other goddesses of smaller size, but similar to herself in appearance, grouped together on a double-headed eagle. 26 These are followed by a number of figures of priestesses clad like the goddess;

and, surveying all, the noble figure of the King-Priest clad in a toga-like garment, and holding a curving lituus, the emblem of his sacred office. 27

That which seems to us in our present enquiry the chief feature of these sculptures is that the worship is clearly common to the god and the goddess, who occupy the leading positions in equal prominence. 28 This interpretation is supported substantially by sculptures which decorate the main entrance of the neighbouring Hittite city of Eyuk. The corner stone on the right represents the goddess seated, 29 receiving the worship of her priests; while the corresponding corner stone on the left shows a Bull-God on a pedestal, 30 with the High

[paragraph continues] Priest and Priestess ministering at his altar. The Bull we have seen to be identified with the chief Hittite deity, which he seems here to replace.

This conclusion is of importance in our present subject, for Lucian (in § 31) describes the chief sanctuary of the great Syrian temple at Hierapolis as containing the common shrine of "Zeus" and "Hera." His very use of these names suggests the wedded character of the deities. Had the shrine been that of the Great Mother alone, the god would not have been accorded an equal prominence near the common altar; he would have been an "Attis," not a "Zeus." The goddess herself would have been in the Greek mind a Rhea or Aphrodite, not a Hera; and Lucian was sufficiently familiar with his subject to be able to discriminate. As it is, he is perplexed in his identification of the goddess by her very comprehensive attributes, which included the many virtues and powers to which the Greek mind assigned separate personifications, known by different names. Speaking generally," he says, "she is undoubtedly Hera, but she has something of the attributes of Athene and of Aphrodite, and of Selene and of Rhea and of Artemis and of Nemesis and of the Fates."

To sum up this stage of our argument, the chief Hittite deity is a god of the skies, identified with the sun; he is all powerful, and in symbolism is identified with the Bull. In formal sculpture he resembles Zeus. The chief Hittite goddess is of

comprehensive character: the emblems in her hand and her youthful companion reveal the nature-goddess; while the mural crown, the lion, and double axe are special symbols of the Great Mother surviving with the Phrygian Kybele (or Rhea). 31 The central Hittite cult is that of this mated pair, the Bull-god Zeus and the Lion nature-goddess. The central cult-images of Hierapolis, as described by Lucian, are exactly similar. There are the mated pair of deities: the god is indistinguishable from Zeus, 32 and he is seated on bulls; while the goddess, who is called for brevity "Hera," as the consort of "Zeus," embodies attributes of the nature-goddess or Great Mother, and she is seated on lions.

The central cult at Hierapolis is thus apparently identical with that which the Hittites had established in the land 1500 years before Lucian wrote. It remains to examine such independent evidences as are available from literary and archaeological sources, to see whether they bear out the argument. We shall find our main conclusion remarkably substantiated. But before passing from the evidence of the Hittite monuments, inasmuch as Lucian's narrative is chiefly descriptive of the developed cult of the nature-goddess (with the god submerged), it is of special interest to notice how widespread are the evidences of her worship in the Hittite period. We

have spoken of two of her shrines in the interior, at Boghaz-Keui and Eyuk. There is a third at Fraktin, in the mountainous country south of Cæsarea. Here the sculptures are carved on the living rock overlooking a stream. 33 The goddess is represented seated behind an altar on which appears her bird. She seems in this case uniquely to wear the Hittite hat, but the carving is not carried out in detail. Before the altar her priestess is pouring an oblation. The counterpart to this group is a Hittite god and worshipper, while between them is a draped altar of special character. 34 One of the earliest of her images, according to Pausanias, 35 is that which may still be seen on Mount Sipylus, near to Smyrna on the western coast a gigantic figure of the goddess seated, carved in the living rock, and distinguished as Hittite handiwork by certain hieroglyphs carved in the niche. 36 Further east, in Phrygia, one of different character has been found at Yarre. 37 In this sculpture, which is on a movable stone, we have one of a series of representations in which the goddess, seated as always, is worshipped in a ceremonial feast or communion. The funerary character of this class of monument is attested by a similar sculpture from Karaburshlu, 38 near Senjerli, in the north of Syria, and other illustrations are found

at Marash, where the cup, mirror, and girdle are instructive details of the scene. 39 The conception of the Great Mother as goddess of the dead is by no means strained or unnatural, for the resurrection and future life is a dominant theme in the universal myth associated with her. And just as the dead year revived in springtime through her mediation, so she may have been entreated on behalf of the dead for their well-being or their return to life. 40 Thus a second class of similar monument represents the goddess enshrined, with a votary in the act of worship or adoration. Such are the two sculptures at Eyuk, one from Sakje-Geuzi, and three from Marash, in the north of Syria. In one of these, from the last-named place, the goddess is distinguished by the child upon her knee, and a mirror and bird accompany the group, which is further remarkable for the lyre before her upon the altar. In others from this place, a bow appears, held in one case in the hand of the worshipper, who proffers it towards her above the altar as though dedicating it to her service and entreating her blessing. A further sculpture in which the goddess plays a part has been found at Carchemish, but details of the scene are not yet available. Other sculptures, resembling these in

general appearance, at Senjerli, 41 Malâtia, and possibly at Boghaz-Keui itself, in which the personages taking part in this ceremonial feast are male and female, may possibly be modifications representing the local king and queen as High Priest and Priestess, or impersonating the god and goddess in the communion rite.

In Glyptic art 42 two varieties of goddess are apparent; the one is robed and seated, and for the most part resembles the deity in her distinctively Hittite character 43; the other is naked, and she has been supposed to have had her origin in this aspect in Syria, whence she penetrated further east. 44 This latter form of goddess has its counterpart in numerous small clay and bronze images, of votive character, which may be found in many places of Northern Syria. 45 In these the goddess is represented as naked, with her hands proffering her breasts. A similar deity, though winged, is represented on a sculptured but undated monument from Carchemish. 46 This is not, however, the Hittite goddess as she is

known in Asia Minor, where she is uniformly represented as seated and robed, and commonly wearing a veil which is thrown back from the face. Nor is she the Dea Syria described by Lucian, 47 though commonly identified with her by modern writers. The reason for this identification is probably to be found in the general tendency towards the development of human passions in connection with the Syrian cults, and emphasized in the special characteristics of Astarte of Phœnicia as the goddess presiding over human birth. 48

The Hittites came and went; their dominion over Asia Minor was subject to repeated onslaughts on every side, from the Egyptians, the Assyrians, the Vannic tribes, the Cimmerians, the Muski and the Phrygians. Their empire, moreover, was held together only insecurely by a system of confederation and alliance which was not apparently of mutual seeking, but imposed by the Hatti during the period of their supremacy at Boghaz-Keui; and from the 12th century B.C. it began rapidly to disintegrate. There is little record of the subsequent events: the Assyrian annals reveal only a series of sporadic coalitions in Syria, to resist their oncoming,

and a temporary revival of the Hittite States in that region during the 10th and 9th centuries B.C. Before 700 B.C. the fall of Carchemish, followed by the submission of the region of Taurus and Marash, brought all semblance of Hittite power to an end. What had happened meanwhile in Asia Minor in the struggles between the Phrygians and the Hittites can only be imagined, but in any case by the year 550 B.C., when Crœsus of Lydia crossed the Halys and took possession of Pteria (Boghaz-Keui), he found it still in the hands of a Syro-Cappadocian population: thereafter the political history of Asia Minor becomes largely that of Persia and Macedonia, of Greece and Rome.

With the Hittites fell their chief god from his predominant place in the religion of the interior. Whether, indeed, he did not survive elsewhere than at Hierapolis, in various local guises or legends, noticeably at Doliche, 49 is a problem into which it would be irrelevant to enter. But the Great

[paragraph continues] Mother lived on, being the goddess of the land. Her cult, modified, in some cases profoundly, by time and changed political circumstances, was found surviving at the dawn of Greek history in several places in the interior. Prominent among these sites is Pessinus in Phrygia, a sacred city, with which the legend of Kybele and Attis is chiefly associated. Other districts developed remarkable and even abnormal tendencies in myth and worship. At Comana, in the Taurus, where the Assyrian armies were resisted to the last, and the ancient martial spirit still survives, she became, like Isthar, a goddess of war, identified by the Romans with Bellona: 50 In Syria, again, a different temper and climate emphasized the sensuous tendency of human passions. In all these cases, however, there survived some uniformity of ceremonial and custom. At each shrine numerous priests, called Galli, numbering at Comana as many as 5,000, took part in the

worship. Women dedicated their persons as an honourable custom, which in some cases was not even optional, to the service of the goddess. The great festivals were celebrated at regular seasons with revelry, music, and dancing, as they had been of old, coupled with customs which tended to become, in the course of time, more and more orgiastic. These are, however, matters of common knowledge and may be studied in the classical writings. Lucian himself adds considerably to our understanding of these institutions; indeed his tract has been long one of the standard sources of information, supplying details which have been applied, perhaps too freely, to the character of the general cult. Religion in the East is a real part of life, not tending so much as in the West to become stereotyped or conventionalized, but changing with changes of conditions, adapted to the circumstances and needs of the community. 51 So, wherever the goddess was worshipped there would be variety of detail. It is, however, remarkable in this case, that throughout the Hittite period, though wedded and in a sense subordinate to a dominant male deity, and subsequently down to the age at which Lucian wrote, she maintained, none the less, her individuality and comprehensive character. Thus, while Lucian is concerned in his treatise with the cult of an apparently local goddess of northern Syria, we recognize her as a localised aspect of the Mother-goddess, whose

worship in remoter times had already been spread wide, and so explain at once the points of clear resemblance in character and in worship to other nature-goddesses of Syria and Asia Minor.

From this general enquiry among the most ancient monuments of the country into the historical origins of the dual cult at Hierapolis, and the character of the goddess, we pass in conclusion to the particular local evidences, more nearly of Lucian's age, that serve to illustrate and amplify his descriptions. There are two chief sources: firstly, the local coins, 52 ranging in date from the time of Alexander down to the 3rd century A.D.; and secondly, the literary allusions of Macrobius, who lived and wrote about A.D. 400. The feature of these branches of evidence that first strikes the enquirer is their obvious reference to a cult and worship which did not change in its essential features throughout the seven centuries of political turmoil which they cover. This enables us to realize how the cult might have been originally established during the remoter days of Hittite supremacy in the land.

The coins are not numerous, but they are profoundly instructive: in particular, one of these, which we shall presently describe, furnishes a direct illustration of Lucian's description of the sanctuary; while two others, which are among the earliest, corroborate in certain details the main point of our argument. In general also, these coins, even those of the later dates, uniformly reveal the goddess as a lion deity; for wherever her full form is shown, she is seated on a lion 53 or on a lion-borne throne. 54 Commonly, however, only her head or bust is given, e.g., in one case, the full face 55 with dishevelled or possibly "radiate" hair; in another, the profile, 56 showing upon her head a mural crown with her veil thrown back. Her name, Atargatis, is recognizable on these coins, though it takes several forms. 57 On this point, therefore, the local evidence confirms the records of Strabo, Pliny, and Macrobius. 58 The

male deity has almost disappeared in the later coins, surviving chiefly in his symbol, the bull, which in some cases occurs singly as a counterpart to the lion or lion-goddess on the opposite side of the coin, 59 and in other cases is shown in the grip of the lion as though reminiscent of the ultimate triumph of the cult of the goddess over that of the god. 60 In similar fashion, the coins of the Roman Empire show an imperial eagle triumphing above the lion 61 in several examples.

In two cases, however, the figure of the god does survive. One of these coins of the period of Alexander, 62 shows upon the obverse the figure of the god seated upon a throne, holding in his left hand a long sceptre, and in the right hand something which is not distinct. On the reverse side of the coin, the goddess is represented clad in long robes, with girdle, seated upon a lion; she holds in her left hand, it would seem, the lightning trident. 63

Instructive as this coin is, it yields in interest to

another of the 3rd century A.D., in which the two deities are shown seated on their thrones, 64 on either side of a central object, surmounted by a bird, exactly like the picture of the sanctuary, which Lucian describes in § 32. The reverse of the coin bears the legend ΘΕΩΙ CϒΡΙΑC (ΙΕΡΟΠ)ΟΛΙΤΩΝ. The object in the centre is an ædicula, surmounted by a dove, and enclosing apparently a Roman standard. 65 To the right is the god, bearded, clad in a long tunic, with a tall calathos on his head, a sceptre in his right hand; he is seated, as it were, upon bulls, but actually upon a throne to which the head and forepart of bulls form the side-piece. On the right-hand side, Atargatis, the Syrian Goddess, is seated similarly upon a throne which two lions support; she is clothed and girdled, and wears a broad calathos or crown upon her head. In the field of the coin, below these representations, there appears a lion. The subject of this coin, is, as we have said, an actual illustration of Lucian's description of the sanctuary: his words are as follows:—"In this shrine are placed the statues, one of which is Hera, the other Zeus, though they call him by another name. Both are sitting; Hera is supported by lions, Zeus is sitting on bulls. . . . Between the two there stands another image of gold, no part of it resembling the others: this possesses no special form of its own, but recalls the characteristics of the other gods. The Syrians

speak of it as Semeïon [σημήϊον], 66 its summit is crowned by a golden pigeon." It is only in reference to this central object that the description fails, though, in both cases, a bird is perched upon the top; and doubtless therefore, the design upon the coin is intended to illustrate something similar to that which Lucian describes. The object upon he coin is formal, architectural, and Roman in character;

Click to enlarge

FIG. 4.—HITTITE DRAPED ALTAR-PEDESTAL: FRAKTIN.

while Lucian tells us particularly that the object between the deities "recalled characteristics of the other gods." We are reminded by this reference of a feature in Hittite sculptures, notably those at Fraktin. Here the pillars of the altars of the goddess and of the god take the form of a human body from the waist downwards, swathed in many folds of a fringed garment or robe; and upon the altar of the goddess appears a bird, doubtless a pigeon

or dove, which was in all tradition her peculiar emblem. 67 Lucian's description is more aptly explained by this symbolism: the object as seen upon the coin had clearly become conventionalized in Roman times. However that may be, the dual character of the cult, the god identified with the bull, the goddess with the lion, is remarkably substantiated.

Further instructive details with regard to these deities are given by Macrobius, and we may appropriately quote from him the following significant passage 68:—"The Syrians give the name Adad to the god, which they revere as first and greatest of all; his name signifies The One.' They honour this god as all powerful, but they associate with him the goddess named Adargatis, and assign to these two divinities supreme power over everything, recognizing in them the sun and the earth. Without expressing by numerous names the different aspects of their power, their predominance is implied by the different attributes assigned to the two divinities. For the statue of Adad is encircled by descending rays, which indicate that the force of heaven resides in the rays which the sun sends down to earth: the rays of the statue of Adargatis rise upwards, a sign that the power of the ascending rays brings to life everything which the earth produces. Below this statue are the figures of lions, emblematic of the earth; for the same reason that the Phrygians so represent the Mother of the gods, that is to say, the earth, borne

by lions." The character, then, of the god and goddess in the sanctuary of the temple, the heart of the cult, remained still the same in the fourth century A.D. as it had been in the beginning. The words which Macrobius uses would be equally descriptive of the special attributes of the Hittite Sun-God and the Hittite Earth-Goddess, which we have described, and the reference to Cybele of Phrygia is also significant. 69 There is indeed a faint memory in tradition of a son to Atargatis, 70 corresponding to the youthful companion of the Hittite goddess at Boghaz-Keui, and hence doubtless to the "Tammuz" and "Attis" of the various legends; and in one of the effigies at Hierapolis it is possible to see a later aspect of this deity corresponding to the Hittite Sandan-Hercules of Ivrîz. 71

If any doubt remained as to the historical origins of the cult at Hierapolis, it would be dispelled by another coin, one of the earliest of the site, on the face of which is the picture and name of the goddess, Atargatis. 72 On the reverse of the coin is seen the priest-dynast of the age (about 332 B.C.): his name is Abd-Hadad, the "servant of Hadad." He is represented at full length, but owing to the wearing of the coin, some of the details are lost. The robe

Atargatis, the Syrian Goddess. Abd-Hadad, the Priest-King.

FIG. 5.—COIN OF HIERAPOLIS, DATE B. C. 332. (Note IN THE BIBL. NATIONALE, PARIS.) Scale 3: 2.

upon him, however, recalls that of the Hittite priest; and the hat which he wears is unmistakably the time-honoured conical hat distinctive of the Hittite peoples. Except in such local religious survival as is here illustrated, this hat must have long fallen into disuse.

In short, the words of Macrobius, which corroborate and amplify Lucian's description of the central cult

at Hierapolis, are strictly apposite to the chief Hittite god and goddess. The coins of the site illustrate the same motive; and on one of the earliest of them, features of Hittite costume are found still surviving four hundred years after the final overthrow of the Hittite States in Northern Syria.

J. G.

1:1 We do not wish to imply a necessarily common "origin" or real identity in the various local aspects of this divinity.

1:2 Among the pre-Semitic population she appears as Nanai. Cf. Ed. Meyer in Roscher's Lexikon—ASTARTE.

1:3 See n. 57, p. 21, and n. 25, p. 9. Cf. Frazer, Adonis, Attis, and Osiris, p. 130, n. 1; Ed. Meyer, Gesch. des Alth., i. (1st edn.), p. 247, § 205.

1:4 Strabo, x. iii. 12; xii. ii. 3.

The probable mention of "Astarte of the Land of the Hittites," as the leading Hittite goddess among the witnesses to the treaty with Egypt (c. B.C. 1271), must be assumed at present to refer p. 2 to Northern Syria. The allusion is none the less significant, implying an identification of the Hittite deity with Ishtar. This rendering of the Egyptian text is due to an emendation suggested by Müller (Vorderas. Ges. VII., 5), and accepted as probable by Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, III., 386, n. a.

2:5 Cf. Inter alia, De Vogüé, Mélanges d’archéologie orientale, pp. 45, 46, and Hauvette-Besnault, "Fouilles de Délos," Bull. Corr. Hell. (1882), p. 484. ff.

2:6 Cf. Frazer, Adonis, Attis, and Osiris, pp. 80, 220; Farnell, Cults of the Greek States, ii., p. 628, iii., p. 305; Ed. Meyer, Die Androgyne Astarte, Z. D. M. G. (1875), p. 730.

2:7 Cf. Pinches, on the Cult of Ishtar and Tammuz, Proc. S. B. A., xxxi. 1909, p. 21.

2:8 Cf. the words, "My son, the fair one" (Pinches, Proc. S. B. A. 1895, p. 65, col. 1, l. 9, of the Lamentation). On the p. 3 other hand, in W. Asia Inscr., ii. pl. 59, 1, 9, Tammuz is said to have been the son of Sirdu. In the epic of Gilgamesh (Ed. Unguad, Das Gilgamesch-Epos, 1911, l. 46, 47) Tammuz is described as the Beloved of [Ishtar's] Youth (cf. King, Babylonian Relig., p. r60). Cheyne, Encyc. Bib., col. 4,893, pointed out that one interpretation of this name refers to Tammuz as a son of life—true divine child.

3:9 By some ancient writers Attis was definitely regarded as the son of Kybele, e.g., Schol. on Lucian, Jupiter Tragædus, 8 (p. 60, Ed. Rabe); Hippolytus, Refutatio omn. Haeresium, v. 9, cited by Frazer, op. cit., p. 219, q.v.: cf. also Farnell, Greece and Babylon, p. 254, and Cults, ii., p. 644, iii. 300, etc. The legends appear in Ovid (Fast. iv. 295 ff.), Pausanias (vii. 17, ix. 10). Though commonly regarded as of shepherd origin (cf. Diod. iii., iv., Theocr. xx. 40; Tertul. de Nat. i.), he was deified and worshipped in common with Kybele in the Phrygian temples (Paus. vii. xx. 2). It is, of course, to his character or fundamental attributes that we allude in our narrative.

3:10 This is not, however, the explanation suggested by Frazer (op. cit., p. 224-237); or by Farnell (Cults, iii., pp. 300-301; Greece and Babylon, p. 257, and n. 1). On the custom itself, see the stirring poem by Catullus, "The Atys," No. LXIII.

4:11 King, Chronicles i., pp. 168, 169; Garstang, Land of the Hittites (hereafter cited as L. H.), p. 323, notes 2, 3; L. H. p. 77, p. 1, p. 323, n. 4.

4:12 Genesis xxiii., xxv. 9, xxvi. 34, xlix. 29, 32. Cf. Ezekiel, xvi. 3, 45; L. H., p. 324, n. 2.

4:13 Winckler, Mitt. d. Deut. Orient. Ges., 1907, No. 35, pp. I, 75. The texts are translated in chronological order by Williams, Liv. Ann. Arch., iv. 1911, pp. 90, 98.

4:14 L. H., p. 326. The sculptures of Sipylus and Karabel (ibid., pp. 167-173) are evidence of the extension of the Hittites to near the western coast.

5:15 Egyptian treaty. Cf. L. H., p. 348. The name of the god in Hittite is not known. Among the Vannic tribes it appears as TESHUB; in Syria, etc., as HADAD; indeed the latter is the general Semitic name, for Lehmann-Haupt has shown that the name of the Assyrian storm-god, as ideographically written, should be read ‘Adad rather than Ramman. (Sitz. Berl. Ak. Wis., 1899, p. 119.) On points of resemblance to YAHWEH see the suggestive paper by Hayes Ward, Am. Jour. Sem. Lang. and Lit., xxv., p. 175.

5:16 L. H., pl. lxxvii., p. 291. Ausgr. in Sendschirli, pl. xli. (i). On the hammer or axe as an emblem of the thunder, etc., cf. Montelius, "The Sun-god's Axe and Thor's Hammer," in Folk-lore, xxi., 1910, p. 60.

6:17 Our Fig. 1, L. H., pl. xliv., Liv. Annals Arch., ii. (1909), pl. xli (4). Cf. the familiar representation in glyptic art of Hadad leading a bull, e.g., Ward, Seal Cyl. of West Asia, Ch. xxx., figs. 456, 459, 461, etc.

6:18 Proc. S. B. A., 1909 (March), pl. vii.; L. H., p. 180, n. 2. The god is identified by an ideogram in the inscription.

7:19 See our Fig. 2, drawn from casts exhibited in the Liverpool Public Museums. Cf. L. H., pl. lxv.

7:20 L. H., p. 239. That this is a divine marriage scene is generally accepted (Frazer, op. cit., p. 108; Farnell, Greece and Babylon, p. 264; cf. Perrot and Chipiez, Histoire de l’Art, iv., p. 630), but it is the recognition that the chief god concerned is not a Tammuz or Attis (as supposed by Frazer, op. cit. p. 105; Ramsay, Journ. Roy. A. S., 1885, pp. 113-120, and others), but the Hittite "Zeus," a form of Teshub or Hadad, that is new in our interpretation and important for our present subject. On the general question of the Hieros Gamos, cf. Daremberg, Saglio and Pottier, Dictionnaire des Antiquités, 1904, p. 177; Farnell, Cults, i., p. 184 ff; Pausanias, ix., 3; and Frazer, The Golden Bough (1890), pp. 102-103. An oriental version of the rite is suggested in the legend recorded by Ælian (Nat. Animalium, xii. 30) that Hera bathed in the Chaboras, a tributary of the Euphrates, after her marriage with Zeus. Cf. the marriage of Nin-gir-su and Baü in Babylonian mythology (Thu. Dangin, Vorderas Bibl., i., p. 77; cf. Jastrow, Relig. of Bab. and Assyr., 1898, p. 59). The details of the scene seem to indicate that the shrine is essentially that of the goddess (cf. Kybele as a goddess of caves, Farnell, Cults, iii., p. 299, and Ramsay, Relig. of Anatolia, in Hastings' Dict. Bibl., extra vol., p. 120), and that the image of the god was carried thereto for this ceremony. (Cf. our note 48, p. 77, also Farnell, Greece and Babylon, p. 268). It is of interest to recall Miss Harrison's arguments, Classical Rev. (1893), p. 24, that Hera had a husband previous to Zeus; also the association of Dodonian Zeus (Homer, Il., xvi. 233; Od., xiv. 327, xvi. 403; Hesiod ap. Strabo, p. 328) with the Earth-Mother in Greece (cf. Farnell, Cults, i., p. 39).

8:21 L. H., pl. lxv. Representations of the youthful god are rare (cf. Farnell, Greece and Babylon, p. 252); the alternative interpretation would be to see in this image an Attis-priest, clad like the god; similarly the second of the two female forms on the double eagle would be the priestess of the goddess in front. This would seem to be made possible by the analogy of a sculpture from Carchemish (Hogarth, Liv. Annals. Arch., pl. xxxv., i.); but the symbols defining all the figures indicate equally their divine rank. This view is accepted by Frazer, op. cit., p. 106.

8:22 For the tradition of a son to Atargatis, completing the analogy of a divine triad, see below, n. 70.

8:23 L. H., pl. lvii. and p. 195. Frazer, op. cit., pp. 98, 100.

8:24 L. H., pl. lxxi. and p. 241.

9:25 The first two may be varied aspects of the great god; the seventh is, however, identical with the local deity of Malâtia. L. H. pl. xliv. (ii.).

9:26 L. H., lxv. The double eagle is found at Eyuk: we may see in this group the nature-goddess in a local dual aspect.

10:27 L. H., pl. lxviii. On his head a cap (cf. Lucian, § 42). His kingly rank is denoted by the winged disc surmounting his emblems.

10:28 That the male god was really dominant would appear from the fact that his name takes first place in the list of Hittite deities in the Egyptian treaty. L. H., p. 348. This agrees with Macrobius' allusion to Hadad of Hierapolis (see below, p. 25). The general prevalence of his worship among the Hittite and kindred peoples is seen in the Hittite archives, the Tell el Amarna tablets, and the Vannic inscriptions. The dual character of the cult is suggested by the seals of the treaty in question, by some of the T. A. letters (e.g., Winckler, Nos. 16, 20, from which the name of the chief goddess among the Mitanni would seem to be accepted as Ishtar), and possibly by the Hittite-Mitanni treaty.

10:29 L. H., pl. lxxiii.

10:30 See our Fig. 3. The bull freely replaces the god on coins of Hierapolis, Tarsus, etc. (B. M. Cat., Galatia, etc. Cf. also Babélon, Les Penses Achéménides, pl. li., vol. 8, pl. xxiv., pp. 20, 22). So also in glyptic art (cf. Hayes Ward, Seal Cyl. of West Asia, ch. lii.). Both at Eyuk and at Malâtia, in the sculpture described above, rams and goats are seen led to the altar as for sacrifice, and the goat accompanies the leading god at Boghaz-Keui. It is interesting to recall the term αἰγοφάγος applied to Zeus (Farnell, Cults, pp. 96, 750, n. 48), and the βουφόνια, a chief rite in the Athenian Diipoleia in the festival of Zeus Polieus. So also in the Cult of Zeus of Attica, a god of agriculture, eating the ox was regarded as a sacrament, the ox p. 11 being regarded as of kin to the worshippers of the god. On Dionysus as a bull and a goat, see Frazer, The Golden Bough, V. (1912), ch. ix. Cf. also our n. 60, p. 22.

12:32 Cf. § 31, p. 70. "The effigy of Zeus recalls Zeus in all its details—his head, his robes, his throne, nor even if you wished it could you take him for another deity." The term ZEUS-HADAD would aptly describe the Hittite deity: it is suggested by the fact that the god of Hierapolis identified with "Zeus" by Lucian is called "Hadad" by Macrobius. Cf. below, p. 25.

13:33 L. H., pp. 150, 151 and pl. xlvii.

13:34 See Fig. 4, and below, p. 24.

13:35 Paus. iii., xxii. 4.

13:36 L. H., pp. 168-170 and pl. liii.

13:37 Jour. Hell. Stud., xix., pp. 40-45 and Fig. 4; L. H., pp. 164-165.

13:38 Corp. Inscr. Hit. (Messerschmidt) (1900), p. 20 and p. xxvi. L. H., pp. 99100, Cf. ibid., p. 100, n. 2.

14:39 Humann and Puchstein, Reisen, Atlas, pl. xlvii-xlix.; L. H., pp. III-112, 119.

14:40 The power of Ishtar to raise the dead is implied in her threat to do so, should the door of Hades not be opened to her. Cf. Pinches, Proc. S. B. A., xxxi. (1909), p. 26. On Kybele (Matar Kubile) as Goddess of the Dead in Phrygian art, see Ramsay, Jour. Hell. Stud., v., p. 245.

15:41 L. H., pl. lxxv., No. 1, etc.

15:42 Cf. Hayes-Ward, The Seal Cylinders of Western Asia, esply. Chs. xlix., 1.

15:43 E.g., ibid., No. 898, where she wears the Hittite hat, and the feet of her throne suggest lion's paws. The lion appears definitely below the throne in No. 908. In No. 907, curiously, she stands on a bull. She is accompanied by a bird in these, as in Nos. 904, 908, 943.

15:44 Ibid., p. 162. The myth of Ishtar's Descent to Hades, however, reveals the goddess naked at one stage of her yearly journey. Ed. Meyer is of opinion (Roscher's Lexikon—ASTARTE) that some of the Babylonian clay figures of the naked goddess are archaic and local.

15:45 Specimens are exhibited in the Hittite gallery of the Liverpool Public Museums.

15:46 Hogarth, Liv. Ann. Arch., ii. (1909), p. 170, Fig. 1.

16:47 Atargatis of Hierapolis is always represented as robed on coins of the site, see below, p. 21, and Figs. 5 and 7, also the frontispiece. There is a small bronze figure in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford (Aleppo, 1889, No. 794), which possibly represents the goddess. The head-dress is debased; but the other features—hair, necklace, dress, and facial expression—are' characteristic and instructive. On the character and relations of the goddess in general, cf. Cumont, "Dea Syria," Real Encyc. (Wissowa), iv., col. 2237.

16:48 Prof. Lehmann-Haupt reminds me that the name Mylitta or Mullitta applied to the goddess by Herodotus (I., 131, 199) is derived from mu’allidatu: The Giver (or Helper) of Birth.

17:49 Doliche is near Aintab, not far north-west from Hierapolis. The worship of Jupiter Dolichenus was introduced to the Roman army by Syrian soldiers (cf. Cumont, Oriental Religions in Roman Paganism, pp. 113, 117, 147 and 263, n. 23; also in Wissowa's Real Encyc. iv., DEA SYRIA, col. 2243). The god stands on a bull holding the lightning and the double axe. (See the illustration in Roscher's Lexikon, DOLICHENUS, and especially the fine sculpture at Wiesbaden, published in the Bonner Jahrbücher, 1901, pl. viii., and compare with the Hittite Hadad of Malâtia, our Fig. 1). His consort is a lion goddess. She is described on inscriptions (C. I. L., vi. 367, 413) by the name "Hera Sancta," which is parallel to the references to the Syrian goddess on inscriptions found at Delos, where the cult had been established by colonists during the second century B.C. ("Fouilles à Delos," Bull. Corr. Hell., 1882, p. 487); thus (in No. 15), Ἁγνῃ Ἃφροδίτῃ Ἀταργάτι καὶ Ἀδάδου; (No. 18) Ἀταργάτει ἁγνῇ θεῷ; (No. 19) ἁγνῆι θεῶι Ἀταργάτει. (Cf. Cumont, DEA SYRIA, loc. cit. col. 2240; also the "Zeus Hagios" of a Phœnician coin, p. 18 Hill. Jour. Hell. Stud., xxxi., p. 62). The Anatolian character of the god is recognised by Kan, De Jovis Dolicheni cultu (1901), p. 3 ff. Cf. also, F. C. Andreas (in Sarre's D. Oriental. Feldzeichen), in KLIO III. (1903), pp. 342-343. So, too, the god and goddess of Heliopolis (Baalbek), identified with the bull and lion respectively, resemble the Hadad and Atargatis of Hierapolis and the original Hittite pair of divinities (cf. Dussaud in Rev. Arch., 1904, pt. ii., p. 246, etc.). Cf. also, the "Jupiter" of the Venasii, Strabo, xii., ii. 6. The subject of the Phœnician and Cilician analogous mated divinities is more complex, but both regions were at one time or another within the Hittite political sphere of influence. An instructive cubical seal from near Tarsus, now in the Ashm. Mus., Oxford (publ. Sayce, Jour. Arch. Inst., 5887, pl. xliv., Messerschmidt, Corpus Inscr. Hit., pl. xliii., i.), shows upon its chief face the two Hittite divinities in characteristic aspect, but the other faces are devoted to the cult of the goddess.

18:50 An emblem of the priesthood of Bellona was the double axe. Cf. Guigniant, Nouv. Gall. Mythol., p. 120; also Montelius, in Folk Lore, xxi. (1910), i. p. 60 ff.

19:51 Cf. the pertinent remarks by Robertson-Smith, Relig. Sem., especially p. 58, on the change of the Mother Goddess from an unmarried to a married state.

20:52 Our chief sources in this regard have been the coins in the Num. Dept. of the Brit. Mus. and in the Bib. Nationale, Paris; Wroth, Cat. of Coins of Galatia, Cappadocia, and Syria (1899); Waddington, in Revue Numismatique, (1861). Six, in Num. Chron. (1878). Babélon, Les Perses Achéménides (1890); Luynes, Satrapies et Phénicie, (1846); Neumann, (Pop. et Regum) Numi Veteres inediti (1783). Hill, on some "Græco-Phoen. Shrines" (Jour. Hell. Stud., xxxi. 9, 11), and "Some Palestinian Cults" (Proc. Brit. Acad., v, 1912). To Mr. Hill we are specially indebted for suggestions and help in this enquiry.

21:53 See our frontispiece, No. 8; Num. Chron., loc. cit.; also B. M. bronzes, No. 51 (date, Caracalla; cf. Wroth, Cat., pl. xvii., No. 16).

21:54 See frontispiece, No. 4, also Fig. 7; Num. Vet., loc. cit.; also B. M. bronzes, Nos. 47, 48, 49 (date, Caracalla, 198-217 A.D.).

21:55 Num. Chron., loc. cit., pl. vi., No. 3.

21:56 Our frontispiece, No. 5 (ibid., No. 4).

21:57 The familiar reading is עתרעתה (see frontispiece, No. 2, and Fig. 5, p. 27), which is separable without difficulty into עתר (‘Atar), the Aramaic form of עשתרת (Astarte) and עתה (‘Até or ‘Atheh); reading thus ‘Atar-‘ate. See note 25, p. 52; and cf. Dussaud, "Notes mythol. Syriees," in Rev. Arch. (1904), p. 226. The legend יכונעתה, Yekun-‘ate (Six, loc. cit., No. 3), indicates the separability of ‘Ate (Atheh) as a distinct name. The legend on our No. 8, עתהט, is possibly a contraction of עתה and (ובה)ט, Cf. Six, op. cit., p. 107; cf. also Movers, Phœn., i., pp. 307, 600. But see Ed. Meyer, Gesch. des Alth., i., pp. 307-308.

22:59 E.g., Brit. Mus. silver coin of Ant. Pius (Wroth, Cat., Gal., Cap. and Syria, pl. xvii., No. 2, also No. 8).

22:60 E.g., Babélon, op. cit., pl. li., No. 18; Num. Chron. (1861), p. 103, rev. Coins of other sites, e.g., Aradus, Byblos, Tarsus, etc., freely illustrate the same themes. Cf. the epithet applied to the Lions of Kybele by Sophocles, Philoktetes, i. 401 (ἰὼ μάκαιρα ταυροκτόνων λεόντων ἔφεδρε). On this point, see Crowfoot, J. H. S., 1900, p. 118, who argues the theme to be symbolical of the death of the god, whether Attis or Dionysus. So Ishtar, in the epic of Gilgamesh, is accused of being the cause of the death of Tammuz, and of her lion (Ungnad, Das Gilgamesch Epos, p. 31, ll. 52 f).

22:61 Cf. Wroth, op. cit., pl. xvii., etc.

22:62 Frontispiece, No. 8; published by Six, Num. Chr. (1878), pl. vi., p. 104, No. 2.

22:63 We have discussed the legend of this coin in n. 57. M. Six (loc. cit.), following Movers, accepts the theoretical reading "Baal-Kevan" as the name of the god.

23:64 See our Fig. 7, p. 70. Publ. Numi vet., pt. ii., tab. iii., 2.

23:65 Six (Num. Chron., loc. cit., p. 119) describes the object as a legionary eagle; but this is somewhat misleading.

24:66 Professor Bosanquet suggests that the Greek word was possibly used in the sense of the Latin Signum.

25:67 See pp. 14, 15, and n. 65, pp. 85, 86.

25:68 "Saturnalia": end of Ch. xxiii.

26:69 In general aspect the Phrygian goddess is indeed hardly distinguishable from the Hierapolitan goddess as described by Lucian. Compare our illustration of Rhea or Kybele, from a Roman lamp (Fig. 8, p. 72), with the representation in Fig. 7, p. 70. This resemblance is further seen in a relief in the Vatican (Vatican Kat., i., Plates, Gall.-Lapidara, Tf. 30, No. 152), described in C. I. L., vi., No. 423: "Superne figura Rheæ cornu copiæ, timone, modio ornatæ, stans inter duos leones"—which, however, Drexler (in Roscher's Lexikon, I., col. 1991) proposes to identify with Atargatis rather than Rhea.

26:70 Xanthos the Lydian relates that "Atargatis" was taken prisoner by the Lydian Mopsus and thrown into the lake at Ascalon (sacred to Derceto; see n. 25, p. 52), with her son Ἰχθύς (Athen. viii. 37). On the proposed identification of the son with Simios, the lover of Atargatis (Diod. ii. 4), etc., see Dussaud, Rev. Arch. (1904), ii., p. 257, who indicates the analogy of the "Hierapolitan triad, Hadad, Atargatis and Simios," with the Heliopolitan, Jupiter, Venus and Mercury. He believes (p. 259) the triad of Hadad to have been of Babylonian origins, implanted at Hierapolis, to reign there through Syria, Palestine and Phœnicia. "Il ne nous appartient pas de rechercher ses migrations et ses influences en Asie Mineure." There is an interesting representation of a Syrian triad in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (1912, 83).

27:72 See our Fig. 5, and frontispiece, No. 2. Publ. Num. Chron., p. 105, No. 5. Choix de Mon. Grecq, pl. xi. 24; Rev. Arch. (1904), ii., pl. 240, Fig. 24 (photo).